Throughout the last twenty years I have focused my research on Russian and Jewish writers. My investigations have led me into the belly of Russian culture—spending great lengths of time with the works of internationally reknowned novelists Dostoevsky and Tolstoy—and also into the Jewish world of synagogues and learned scholars. The people I have studied encountered and survived plagues, and during this moment of our pandemic I’ve found myself returning to them to gain insight and, perhaps, comfort.

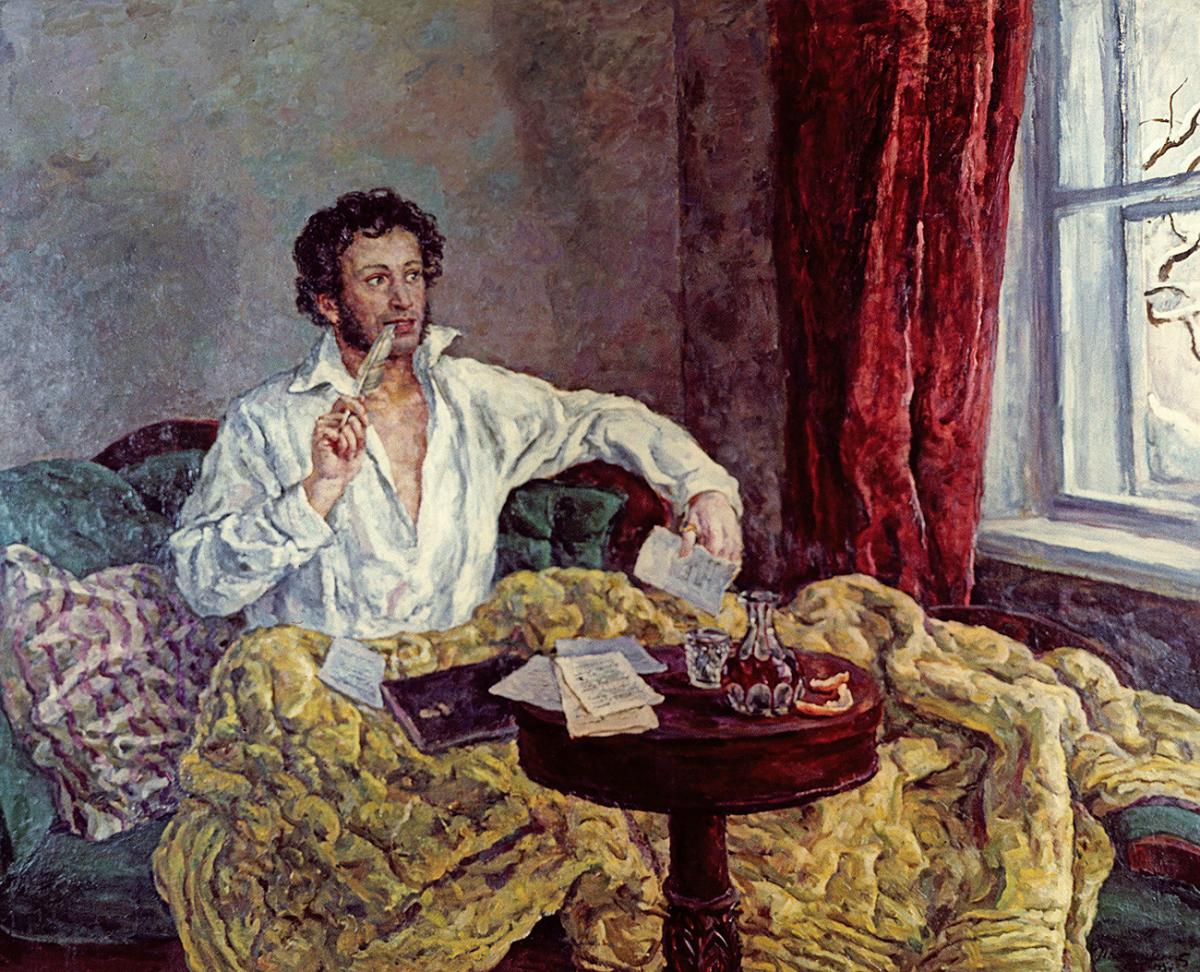

This first person that has been weighing on my mind is Alexander Pushkin, known as the Russian Shakespeare, although in truth many in Russia know Shakespeare as the English Pushkin. During the cholera epidemic of 1833, Pushkin was unable to leave his country estate in the village of Boldino. It was a terrific period of blossoming for him, known as the “second Boldino autumn,” and he wrote some of his best poetry in the country, including his magnificent work “The Bronze Horseman.” But it became clear that he had witnessed a great deal, and the deaths from the plague forced him to ruminate and examine his own mortality. In letters to his wife and friends, he began to imagine his own death, to feel that his time was limited.

When he returned to the capital, St. Petersburg, he faced pressure from various directions. Not everyone admired his unearthly talent. Tsar Nicholas envied him and unleashed the obsequious courtiers who pursued the poet. They trumpeted the cruel opinion that his muse had abandoned him; his talent was finished. They also spread the painful rumor that his wife had cuckolded him and with the tsar, no less. In 1833, Pushkin had boldly mocked cholera, but the spreading epidemic of disdain for his ideas and his creative self, turned out to be fatal. In January 1937, he died in a duel to protect his wife’s honor.

Another hero who has influenced me greatly is Mikhail Gershenzon. Plague emerges here again around a debate over revolution, which erupted in 1905 and then twice in 1917. My story takes place in 1910, after the failed 1905 uprising, and concerns two intellectuals born as Jews, although one converted to Russian Orthodox Christianity and the other was non-practicing. The two men wrote a series of letters in 1909 and 1910 in which they argued about Landmarks, a controversial book that condemned revolutionary violence.

Gershenzon, the editor of Landmarks, sharply criticized radicals. He argued that intellectuals in Russia had occupied themselves exclusively with overthrowing the tsar and look where it ended—with nothing achieved. It was time, he claimed, for people to look inward for their happiness and stop expecting change to occur from outside, via a transformation in the political situation. His interlocutor, Semyon Vengerov, disagreed with Gershenzon. In his criticism, Vengerov repeated the refrain that the radicals made up Russia’s best people, its idealistic intelligentsia. An attack on the intelligentsia, Vengerov claimed, was morally despicable.

"But it became clear that he had witnessed a great deal, and the deaths from the plague forced him to ruminate and examine his own mortality. In letters to his wife and friends, he began to imagine his own death, to feel that his time was limited."Brian Horowitz

Vengerov invited Gershenzon to come from Moscow to St. Petersburg to “have it out, one-on-one.” Gershenzon asked for a rain check, noting the cholera epidemic that prevented travel. Vengerov mocked him, “Cholera isn’t interested [in infecting] those who defend Landmarks.” Gershenzon did not travel to meet Vengerov but waited until the epidemic was over before heading from Moscow to St. Petersburg. The two were reconciled later after the Bolshevik Revolution when their situations as outcasts and representatives of the old guard grew close. At that time Vengerov could not refuse to admit his mistake; the Russian revolutionaries had chosen the wrong goal, and he and Gershenzon were now paying a dear price.

To these anecdotes, I want to add another that deals with the present pandemic and concerns a young woman in Moscow. Her dilemma is this: she wanted to attend an annual “meeting” devoted to the memory of innocent citizens repressed by the Stalin regime, but was unsure whether the risks of catching Covid-19 either from a co-participant or the police—if she were arrested—was worth it. Most of life’s essential events, she told me, occur in private, but some are communal, public, and require a mass of people. She wanted to pay respects to her ancestors and to give voice against political repression but was unsure whether she would go. Her situation reminded me of the dilemmas of young people in the U.S. Can political protest be done safely during a pandemic?

My daughters recently went to a protest, but I worried about masks, social distancing, getting infected. Was my worry a form of inaction? I wanted to encourage my daughters to stay home. Some things cannot be done in private, but public activity is dangerous these days. What does that realization signify for the body politic? Ruminations of these people—Pushkin and his creativity, Gershenzon and Vengerov’s debates over politics, the Moskovite’s appreciation of public memory, and my daughters’ desire for a better world—are linked by the coronavirus. And yet again my mind wanders. Plague doesn’t really change the essence of life. Pushkin hadn’t lost his talent, in fact it was ripening with age; intellectuals still debate about revolution; and protestors take to the streets when the political establishment cannot respond to their needs. Fathers too continue to worry about daughters and second guess whatever decision they make. This plague, like those before it, begins to appear merely as one of many considerations that perplex the mind. Set against the pandemic, my own life returns to a new normal in which Covid-19 is given its due (I have a mask at the ready), but in which responsibility to other values gradually dislodges the monopoly of fear.