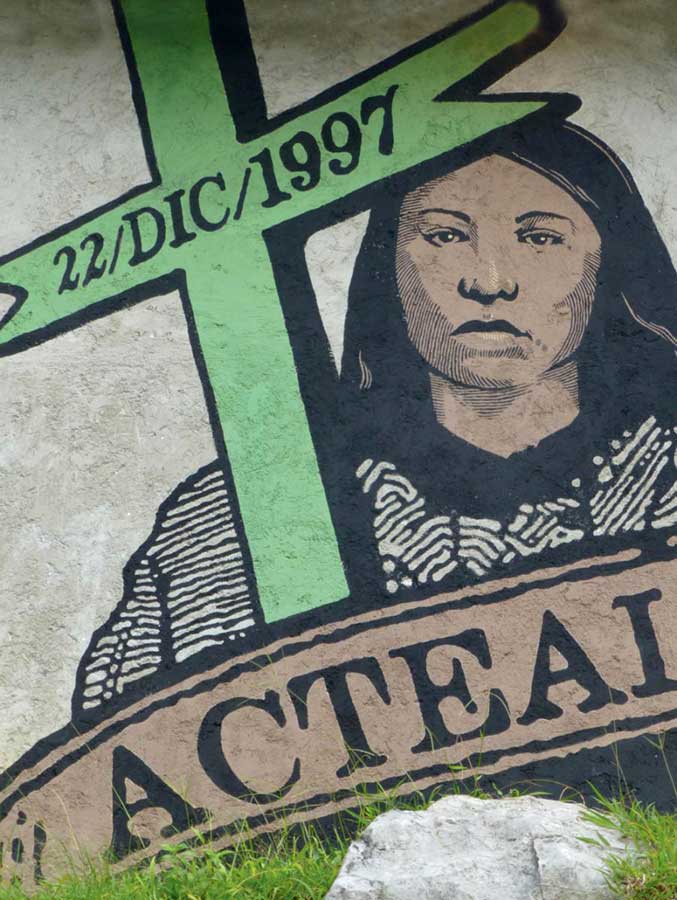

A mural in Acteal, Mexico, commerates the day of the Acteal Massacre, December 22, 1997.

EMILY WILKERSON: You are a cultural anthropologist—what exactly does this mean?

CLAUDIA CHÁVEZ ARGÜELLES: As a cultural anthropologist, I study people’s everyday lives and their communities, including their behaviors, interactions, beliefs, and institutions. Every aspect of the human experience can be approached from a cultural anthropological perspective: law, politics, sexuality, health, religion, and so on. We look for patterns of meaning to develop explanations of social phenomena, with a particular emphasis on intersectional power dynamics. The subfield of cultural anthropology revolves around the understanding that there are many other ways of seeing the world aside from Western perspectives—we seek to make “the familiar strange, and the strange familiar,” as the famous epithet says.

EW: And you were a civil and family lawyer in Mexico before becoming an anthropologist. Can you tell me about this transition?

CCA: This transition took place in the context of the 2001 constitutional reform on Indigenous rights in Mexico. State officials presented this reform as the beginning of a new era of their relationships with Indigenous peoples. However, Indigenous peoples were not properly consulted in its creation, and the reform violated previous agreements between the state and the Zapatista National Liberation Army. This situation sparked my curiosity about the practical reach of this legal recognition and the ways it would affect Indigenous practices of justice. To approach these issues, I first needed to understand how Indigenous peoples conceive of their normative systems and how they navigate Indigenous, state, and international laws when seeking justice. Cultural anthropology equipped me with the theoretical and methodological tools that I needed to embark on this study and engaging in ethnographic fieldwork transformed my perspective on legal recognition, pushing me to rethink my identity as a mestiza and a lawyer.

EW: What are some of the most important values that drive your work?

CCA: A commitment toward decolonization, social justice, anti-racism, reflexivity, collaboration, compassion, and accountability. The Zapatistas have inspired many of these and other horizons that guide my work, like their firm belief that another world is possible; the notion of horizontality as a form of leadership, which is opposed to verticality and hierarchical understandings of power; and the practice of sentipensar (feel-think), which means to co-reason with the heart. My training in activist/politically engaged/feminist anthropology has also shaped how I understand my accountability as a scholar. Activist research entails co-creating transformative knowledge with a group of people you share political goals with, and collaborating in their struggle as a key part of the research process. This approach questions positivist notions of objectivity and disrupts the traditional power dynamics of research, fostering a more egalitarian distribution of its benefits among participants.

EW: You’ve been researching and writing about the transgenerational effects for Maya victims of state violence and their ideas of justice for multiple years now, particularly focusing on the 1997 Acteal Massacre in Chiapas, Mexico, against the Indigenous organization Las Abejas. What does your field research look like in Chiapas, and how do you enact your training as an activist anthropologist?

CCA: When the Mexican Supreme Court of Justice freed those who the survivors saw as the perpetrators of the Acteal Massacre, I realized that my training and connections as a lawyer and an anthropologist could be useful to the community of survivors. I took on the task of tracing the routes of multiple representations of the massacre in the judiciary, media, academia, and across advocacy networks in order to demonstrate their distortion of survivors’ testimonies and historicize the construction of the “legal truth” about the Acteal case. In this sense, my work aims to visibilize deadly erasures that have been made in the name of objectivity, positivism, and justice. Before beginning to track these connections, I first had to become familiar with Indigenous survivors’ perspectives and discuss with Las Abejas and their lawyers the possibility of using research as evidence in their struggle for justice in international arenas. As part of the collaboration we negotiated, I participated in the preparation of a psychosocial expert testimony along with other specialists in topics of state and gendered violence. The expert testimony was based on participant observation, workshops, and extended interviews with Las Abejas’ survivors, past and present authorities, and mestizo lawyers, activists, priests, scholars, and doctors. To avoid asking survivors to retell their experiences of the massacre, I conducted extensive archival research and systematized seventeen years of survivors’ testimonies of the event. We aimed to prove that the massacre’s effects have extended beyond the day of the slaughter to the present. Las Abejas submitted the expert testimony before the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) in 2016. Four years later, they are still demanding the IACHR to issue its Merits Report. Following their struggle for justice continues to be part of my research.

EW: What advice do you offer your students embarking on field research?

CCA: In my course “The Politics of Fieldwork,” I guide students to develop a collaborative, ethical, and decolonizing approach to ethnographic fieldwork, sensitive to racialized-gendered dynamics. I encourage students to be honest with themselves about their motivations for conducting research, and to keep asking themselves “why” several times until they feel they have fully understood what is really propelling them in this path. As a question of responsibility toward the people you are going to work with, I think it is critical to know yourself before embarking on fieldwork. It is not enough to have an extensive knowledge of the topic you are studying; you also need to explore its ties to your personal history. Fieldwork is a transformative experience for all of those involved, and you need to be very clear about what you are bringing to the table. This applies to our everyday interactions beyond fieldwork as we develop more awareness about the interconnectedness of our liberation.

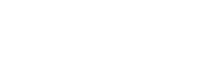

During the twentieth anniversary of the Acteal Massacre in Chiapas, Mexico, members of Las Abejas and their allies held a spiritual ceremony for victims. Claudia Chávez Argüelles, an assistant professor in the Department of Anthropology, was present at the ceremony, which included singing "No puedo callar. No puedo pasar indiferente ante el dolor de tanta gente. ¡Yo tengo que cantar la libertad!" and prayers, offerings, and a procession with crosses inscribed with the names of those massacred in 1997. Photos provided by Claudia Chávez Argüelles.