2025

Board Game Brings Russian Literary Classic to Life

Spring 2025

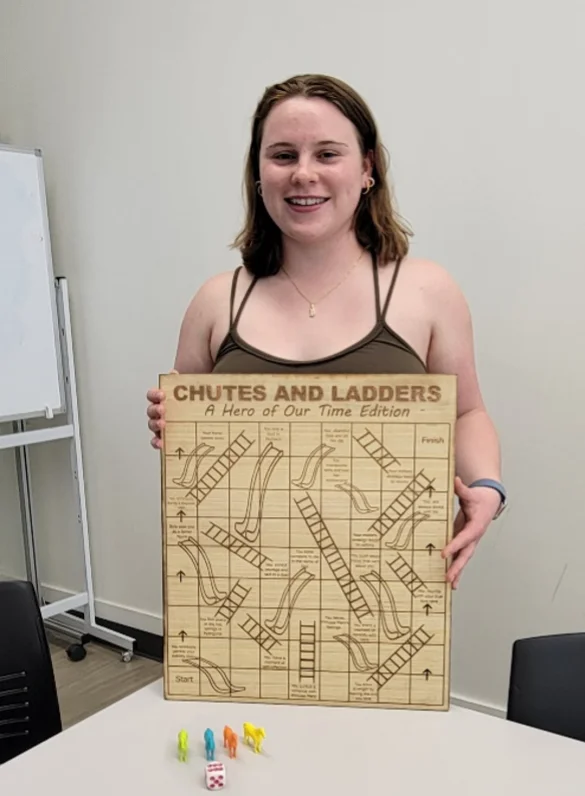

In Spring 2025, Aubrey Augustine (Class of ’25), a double major in Russian and Physics, created a remarkable interdisciplinary project for the course RUSS 4820 – Writing the Empire: Russian Literature & Colonial Encounters, taught by Prof. Zhigunova. As a creative response to Mikhail Lermontov’s 19th-century novel A Hero of Our Time, Aubrey designed and built a fully functional board game inspired by the classic children’s game Chutes and Ladders.

Titled Chutes and Ladders – A Hero of Our Time Edition, the game integrates key events, character arcs, and themes from Lermontov’s novel, cleverly mirroring the protagonist Grigory Pechorin’s unpredictable moral trajectory. What makes the project especially unique is Aubrey’s use of the Tulane Makerspace: she laser-cut and 3D-printed the entire game board, dice, and horse tokens—merging her technical expertise in physics with her literary analysis from Russian studies.

Aubrey Augustine:

“After reading A Hero of Our Time, I was inspired to create a board game for my creative assignment aimed at gaining a better understanding of the novel. To make my game, I combined my skills from my physics degree, such as working in the Makerspace, and my interest in Russian studies, culminating in a game board and game pieces crafted from laser cutters and 3D printers The result was a hands-on, immersive way to engage with the story’s structure and characters.”

Prof. Lidia Zhigunova:

“Aubrey’s project was both innovative and intellectually rich. Her game thoughtfully engages with the novel’s narrative structure and moral themes. The use of Chutes and Ladders as a format was especially clever—it reflects Pechorin’s unstable moral compass and the highs and lows of his choices. It’s a brilliant example of what can happen when STEM and the humanities come together.”

The project was part of a broader creative assignment where students reimagined A Hero of Our Time in new formats, while remaining faithful to Lermontov’s tone, themes, and style.

Lindsey Cliff Selected for Prestigious NYU Jordan Center Symposium

Tulane Honors student Lindsey Cliff (’25), a double major in International Relations and Political Economy with a minor in Russian, was one of only 19 undergraduates nationwide selected to participate in the NYU Jordan Center for the Advanced Study of Russia Masters and Undergraduate Research Symposium (March 14–15, 2024). The Jordan Center covered all costs for participants.

At the symposium, Lindsey presented her research, “Supporting Change or Stifling Voices: Reassessing International Advocacy in the Post-Soviet Space,” based on her internship with the Khodorkovsky Foundation. Her talk examined the role of Russian non-profits and opposition groups in exile, highlighting both their positive impacts and the challenges they face—including the continued marginalization of non-Russian voices.

Reflecting on the experience, Lindsey noted:

“In the context of my internship with the Khodorkovsky Foundation, I reviewed the impact of Russian non-profits and opposition groups in exile. I highlighted positive impacts and then discussed institutional and logistical challenges facing these groups. The last portion of my presentation took a more critical tone. I reflected on an instance of self-censorship during my internship. I was asked to pivot the focus for memos and briefs from ethnic minorities in the periphery to ethnic Russians in Moscow and St. Petersburg. I used this example to discuss the broader issue of the continued marginalization of non-Russian voices in the opposition.

It was very interesting to see that a majority of the presentations focused on the periphery of the former Soviet world or non-Russian voices… I was surprised by how Kazakh language and literature, Georgian politics, and Ukrainian voices were elevated.”

Since 2021, Lindsey has been an outstanding student in Tulane’s Russian Program, excelling in language courses and advanced seminars such as Narratives from the Post-Soviet Borderlands: Russia and the Caucasus and Disentangling Eurasia: Identity and Conflict in the Post-Soviet World with Prof. Lidia Zhigunova. Her selection for this prestigious symposium reflects her academic excellence and deep engagement with the politics, cultures, and histories of Eastern Europe and Eurasia.

Hope Between Borders

Sam Tarpley is a Master's student in the Department of English. He is a WACNO intern and an Andrew W. Mellon Fellow in Community-Engaged Scholarship. His work in relaunching WACNO’s Academic World Quest motivated him to study abroad in Latvia during his winter break in 2023-24. Upon returning, he applied for and received a Boren Fellowship. This allowed him to spend six months in Riga, Latvia, studying Russian and Information Security and Conflict Resolution. Recently, Sam has been named a semi-finalist for the Fulbright ETA program in Kazakhstan. At WACNO, Sam works to bring accessible and inviting international education to the Greater New Orleans area.

Time has a particular way of passing us by when we have the fortune to return to the places we call home. And yet, so much can change when the ability to return home is taken away. For some, this is not only a reality, but a lived experience permeated through crisis, uncertainty, and war. On the third anniversary of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, families and countless lives are continually being fractured between borders — and despite these challenges, hope persists. I’m proud to see my Tulane and New Orleans communities answering the call, and with the World Affairs Council of New Orleans (WACNO), the impact of those experiences is coming to life through the power of spoken word.

An internationally minded organization, WACNO is dedicated to bolstering awareness of global issues in the greater New Orleans area, and it is the great diversity of our port city that allows for this communication across cultures. Since the onset of the war in Ukraine, WACNO has advocated for all those who have been displaced, offering not only a platform for experts to sustain public discourse, but a place for the Ukrainian population in New Orleans to foster solidarity — all the while portraying how even the most stringent of challenges may be overcome through community.

As an Andrew Mellon Fellow in Community-Engaged scholarship, I discovered the breadth of international outreach possible in our city, first as a student of Russian language at Tulane, and later as a contributing member of an organization that continues to effect change. Partnering with WACNO for the Mellon Fellowship, I have been able to contribute to causes that exist not only locally, but globally. Broadening my horizons in this way, my service with WACNO has ranged from tutoring immigrants to sparking social change through art — and I’m eager to see how this journey will continue to take shape.

Set against the reverence of the Marigny Theater, WACNO cultivated a new sort of conversation beyond collectivity and into history. At a panel discussion on February 24, in partnership with the Louisiana Endowment for the Humanities, a moving work-in-progress documentary was unveiled — showcasing the oral histories of Ukrainian refugees now residing in the state we call home. In the coming weeks, this collection of lives and voices will become a permanent part of the Williams Center for Oral History at LSU, standing as a testament to the history being made in front of us all.

Alongside WACNO President, Dr. Alla Rosca, I took part in these interviews, exemplifying the interconnectedness not merely between university settings, but in the very city of New Orleans. Witnessing these candid accounts of adversity and real hardship marked a pivotal juncture in my understanding of identity juxtaposed by language — Ukrainian, Russian, and English. This was the very concept School of Liberal Arts Professor Lidia Zhigunova made critical in each of her classes at Tulane. As a panelist and member of WACNO herself, she emphasized how matters of imperialism across her native North Caucasus region, now a part of Russia, have intruded upon the preservation of culture and belonging itself. As she placed this divide into the context of today, we were all reminded of how the saliency of identity can be influenced by the language we speak and the places where we feel safe. In the North Caucasus as in Ukraine, these matters continue to arise — and it’s why reclaiming home through these conversations will keep us all moving toward a future worth hoping for.

2024

Tulane’s Sam Tarpley Earns Prestigious Boren Award

When Sam Tarpley arrived at Tulane as an M.A. student in the English Department, his academic path had already taken an important turn. The summer before starting his program, a meeting with the Office of Fellowship Advising and encouragement from Dr. Thomas Spencer inspired him to pursue a critical language. Influenced by a former undergraduate professor, Sam chose Russian - beginning with a virtual summer course from St. Petersburg before continuing his studies at Tulane with Professors Lidia Zhigunova and William Brumfield.

At Tulane, Sam became a Mellon Foundation Fellow in community-engaged scholarship. With Professor Zhigunova’s guidance, he connected his interests in language, culture, and conflict to an internship at the World Affairs Council of New Orleans, where he helped relaunch the Academic World Quest program and supported panel discussions with international experts.

Sam’s growing passion for the post-Soviet world led him to study abroad in Latvia over winter break, an experience that motivated him to apply for - and win - a prestigious Boren Fellowship. In Latvia, he immersed himself in Russian language and literature courses taught entirely in Russian, studying alongside peers from across Europe and beyond. Outside the classroom, he volunteered with YoungFolks Latvia, a youth organization supporting refugees and fostering community. His dedication paid off: he completed the equivalent of nearly two semesters of Russian study and earned high scores in the verbal and reading sections of the Test of Russian as a Foreign Language (TORFL).

Beyond academics, Sam deepened his understanding of Baltic-Russian relations, meeting with diplomats in Riga and learning about the Latvian economy at the Parliament (Saeima). Recently named a Fulbright ETA semifinalist for Kazakhstan, Sam hopes to continue applying his language skills and regional expertise toward a future career in international law.

2023

Max Weber – Backpacking from Almaty to Tbilisi: The Importance of Looking Beyond Russia

Stepping cautiously onto the tarmac of Almaty International Airport, soft flakes of early-January snow dusted my sole piece of luggage: a trusty old hiking backpack. Cloaked in the waning darkness of a frigid Kazakh morning, the ice beneath my boots gleamed under the dim glow of Cyrillic neon signs. I checked my phone: -15 degrees Fahrenheit at 7am. Yikes. As the sun’s pale light peaked over Central Asia’s vast snow-capped mountains, I shivered in the biting winter wind. Much to my chagrin, the locals around me (clearly accustomed to the hostile weather - and eager to show it) noticed.

“American?”, a middle-aged woman asked in Russian, pulling back her headscarf.

“Yes,” I stammered. I didn’t think it was that obvious.

“You need vodka,” her tall (and, admittedly, rather imposing) husband told me. “Vodka keeps you warm.”

I laughed (fifteen minutes in the post-Soviet periphery and I had already been offered vodka) and we continued into the terminal. Stepping across the wet tile floor and up to the smudged glass of a custom’s booth, I dug into my backpack for the little blue book that would serve as my key into (and out of) six countries over the next two and a half months. As I handed my passport to a young military officer, he yawned, then looked me over casually.

“State the purpose of your visit,” he declared in Russian.

I paused. For a split second, a whirlwind of thoughts and emotions swirled in my head. In completing the flight to Almaty, I had finished the first step of a solo journey I had dreamt of for months.

The problem, however, was that my journey had only one other concrete step. Just one: a plane ticket out of Tbilisi, Georgia… over two months later. Apart from visas into Uzbekistan and Azerbaijan (which could be activated at any point), I had literally zero plans connecting my journey between the Almaty and Tbilisi airports. In other words, my trip would ultimately be defined by a single, all-consuming goal: to improvise as hard as I’d ever improvised before.

I didn’t know it at the time, but over the next 60+ days, I would hike, hitchhike, couch-surf, take trains and buses, and make deep friendships from Kazakhstan to Georgia before returning home in March. I would help teach English to Uzbek schoolchildren during citywide power outages, trek through the mountains with Kyrgyz farmers, share traditional meals with Ukrainian refugees, attend Georgian Orthodox ceremonies in ancient cathedrals, narrowly avoid arrest for carrying a banned book across the Kazakh/Uzbek border, get interviewed on TV in Tashkent, and so much more.

So, as the flurry of emotions faded, a thought sprung into my mind: had I just begun the best game of ‘connect the dots’ ever played?

“Um…tourism,” I replied. He stamped my passport, handed it back, and smiled knowingly.

“Welcome to Kazakhstan”

THE IMPORTANCE OF LOOKING DEEPER

Writing this article in early August, I can proudly say that I’ve made it back from my travels alive and well… and, surprisingly, without a criminal record in any of the countries I visited. As such, a few reflections are in order.

Pause for a moment. Take a deep breath. Now think about the term “Slavic studies”.

What are you picturing? Chances are, and if you’re anything like I was when I first decided to study Russian, you’re thinking of Russia itself. The Russian Federation is by far the most powerful political and military player in the region. It also receives (again, by far) the most media and academic coverage, especially in light of the recent invasion of Ukraine.

As such, the picture of “Slavic Studies” that resides in the heads of most people features colorful Orthodox onion domes, fluttering Soviet banners, and horrors committed by Russian president Vladimir Putin against Ukraine. This is entirely understandable, after all. Russia has a long and fascinating history which has - for many years - been marred by dictatorship, atrocities committed both internally and externally, and conflict on a truly global scale. It is therefore only natural that many people’s knowledge of the region focuses uniformly on Russia.

However, Russia’s central role in public discourse tends to limit our view of Slavic studies to Petersburg and Moscow. With the attention we dedicate to Russia, I believe, we tend to forget about the countries and peoples which have for centuries existed not only in their own right, but as fundamental influences on Russian and Slavic culture and the international landscape as a whole. The Tatars, the Chechens, the Kazakhs, the Georgians - these and other post-Soviet people have long, intricate, and deeply fascinating histories that are intertwined with our conception of Russia and Eastern Europe, whether we recognize it consciously or not.

With this in mind, it was one specific aspect of my Russian major that defined my fascination with the region, rousing within me not only the desire to visit Central Asia and the Caucasus but to dedicate my career to studying the area as well. This aspect is what gave me a deep respect for the many vibrant cultures comprising the post-Soviet world and, with only a few months until the due dates of my first round of graduate applications, convinced me to spend (hopefully) the rest of my life studying them:

Tulane’s Slavic Studies department approaches the Russosphere in a manner that stretches far, far beyond Russia itself.

Including the Caucasus, Central Asia, and Eastern Europe as core components of the program isn’t simply a novel approach to Slavic Studies. As discussed above, I thoroughly believe that viewing the region through an inclusive lens is indispensable when attempting to gain a complete understanding of the post-Soviet landscape. Russia as we know it is an intricate tapestry of intermingled cultures and ethnicities scattered both within and throughout its borders.

Studying under both Dr. Lidia Zhigunova and Dr. William Brumfield, I could tell clearly that our departmental curriculum was engineered to shed light on the critical importance these cultures should hold in Slavic and Eurasian studies. A member of the Circassian diaspora, Dr. Zhigunova hails from the region of Kabardino-Balkaria in Russia’s North Caucasus. As such, she is uniquely able to discuss the significance and cultural beauty of minority communities both within and around Russia, often speaking from personal experience and sharing anecdotes from her childhood. Narratives from the Post-Soviet Borderlands, the first Russian class I ever took, is a case in point - it merged the study of literature, culture, and politics with her personal experience to create a profound perspective on Russia and the surrounding countries. Dr. Brumfield, too, ensures that his courses venture beyond western Russia; renowned globally for his spectacular photography and scholarship on Russian architecture, he has traveled extensively throughout the Russian north and Central Asia. As a result, his classes place Russia, the Russian language, and current events within a broad and vivid geopolitical and cultural context.

It is clear, then, that the Tulane Department of Germanic and Slavic Studies’ approach to studying the post-Soviet landscape is uniquely powerful in its ability to shed light on often overlooked cultures. Via the guidance of my professors, I took a deep dive, headfirst, into a region few people know much about.

And the best part is, I’ve only just scratched the surface.

So how does this all tie back into my grand escapade from Almaty to Tbilisi? How did I go from reading The Railway by Hamid Ishmailov as a sophomore at Tulane to, three years later, being stopped at 3am by the Uzbek military for carrying The Railway by Hamid Ishmailov across the Uzbek/Kazakh border?

The answer is simple: having had the privilege to study within a department that actively prioritized the post-Soviet space’s minority communities, I caught a glimpse of the beauty, complexity, and vibrancy of an often overlooked region of the world. As I passed through four years at Tulane, this glimpse grew into an overwhelming fascination. And then, as I graduated from Tulane, I knew that this fascination would be a permanent fixture in my personal and professional lives, one which would guide my future goals as I continued to dive deeper into the region.

I chose to follow this passion halfway across the world, leading me on adventures and intellectual journeys I would never have thought possible just a few years prior. I trekked to tiny villages and strolled through big cities, attended services in cozy Eastern Orthodox churches nestled in the mountains and wandered through massive Madrasahs in the desert. Across each of these, my experience was grounded in a deep curiosity - developed over the years prior - about their role in the local culture and my perception of the post-Soviet world overall.

This is going to sound cheesy (and no, I’m not paid to say this), but Tulane’s Russian Program changed the way I see the world and permanently altered the trajectory of my life. I am grateful, on a level that I can’t quite express in writing, to Dr. Zhigunova and Dr. Brumfield for the inspiration they have handed to me.

I only hope that you can follow the same path. Personally, I think Georgia is where it’s at… and not just because of the amazing food… or wine. Georgia is a deeply fascinating country for myriad reasons, cultural and political. Its tumultuous relationship with Russia and Europe puts it subtly at the center of modern geopolitics, while its food, art, and music are breathtaking in their own right.

But for you, the opportunity to go out and learn about these places is there. Maybe it’ll be Uzbekistan, maybe Chechnya, maybe the Circassian diaspora in New Jersey. Or maybe you’ll treat this opportunity as a way to just gain a deeper look into new cultures, whether you want to study them further or not.

Regardless, all you have to do is sign up for a class… or two… or maybe nine. Heck, just go ahead and major in Russian already.

Alright, that’s all from me. In lieu of an eloquent Georgian toast, ჭაჭის დროა!

Max Weber graduated from Tulane in 2022, triple majoring in Russian, Political Economy, and Political Science; he is the Founding Editor-in-Chief of the Tulane Journal of Policy and Political Economy, Tulane University 2022.

2022

The View from Abroad: Stories from Russia During its Invasion of Ukraine

May 2022

By Isabel Rodriguez

I’m Isabel Rodriguez, a graduating senior at Tulane majoring in Russian and Homeland Security Studies. In January, I traveled to Moscow for a language immersion program - an experience that quickly became more than I had imagined. Just weeks after my arrival, Russia invaded Ukraine, and I witnessed firsthand the shock, uncertainty, and rapid changes that followed. From empty banks and broken supply chains to riot police blocking protest squares, the final days of my stay revealed a side of Russia few outsiders ever see.

Leaving was difficult—especially saying goodbye to my host mom—but the experience deepened my understanding of how Russians view the war, the limits on free expression, and the resilience of those who oppose it. I returned home with a stronger commitment to my studies and a renewed solidarity with the Ukrainian people.

Read the full story on the Center for Global Education website.

Two Russian Majors Recognized with Tulane’s Highest Academic Honor

May 2022

Max Weber and Kathryn Elder, both Russian majors from the Class of 2022, were inducted into the William Wallace Peery Society, the university’s most prestigious academic honor for undergraduates. This recognition is awarded to students who demonstrate exceptional scholarly achievement, intellectual curiosity, and a strong commitment to academic excellence.

Their accomplishment highlights the dedication and talent of our Russian Program students, and we are proud to celebrate their success as part of the Tulane community:

2018

Student Awarded Prestigious Beinecke Scholarship

May 2018

Kathryn Cook, a junior pursuing a double major in history and Russian, has been selected as a 2018 Beinecke Scholar. The Beinecke Scholarship encourages highly motivated students who have demonstrated superior intellectual engagement and academic ability to be courageous in their pursuit of graduate study in the arts, humanities and social sciences. The scholarship supports this pursuit with a $34,000 award. Tulane can nominate one student each year for this selective award. Cook was one of only 18 Beinecke Scholarship winners in 2018.

Cook’s study of history and Russian has inspired in her a passion for public history and theories of public memory, especially as they relate to various ways that World War II is represented in museums and memorials in international contexts. Cook’s academic interest in this area was further inspired by an internship at the National World War II Museum in New Orleans, where she focused on children’s programming.

"I am very honored to have this opportunity and am very thankful for the support of both Tulane and the Beinecke Foundation.”

- Kathryn Cook, School of Liberal Arts student

“The Beinecke Scholarship will provide support for graduate study at a program of my choice,” says Cook. “I am planning on pursuing a PhD in history, focusing on historical memory regarding the Second World War in Europe, and later to pursue a career in museum work. I am very honored to have this opportunity and am very thankful for the support of both Tulane and the Beinecke Foundation.”

The Beinecke Scholarship Program was established to provide substantial scholarships for the graduate education of students of exceptional promise. Since 1975, the program has selected more than 628 college juniors from more than 110 different undergraduate institutions as recipients.