Biography

Michelle Foa is Associate Professor of Art History in the Art Department of Tulane University, with a focus on French art and visual and material culture of the later 19th and early 20th centuries. Her first book, Georges Seurat: The Art of Vision, was published in 2015 by Yale University Press. She is currently working on a book on Edgar Degas that analyzes the artist’s experimentation with a wide range of supports, media, and processes in the broader context of discourses on matter and materiality in later 19th-century France. Other research interests include the materials of art, Europe’s global encounters in the 18th and 19th centuries, the relationship between art, science, and technology, and art historiography and criticism. Before coming to Tulane in 2008, the year that she completed her doctorate at Princeton University, she taught at Mount Holyoke College, the University of Pennsylvania, and Princeton.

Research

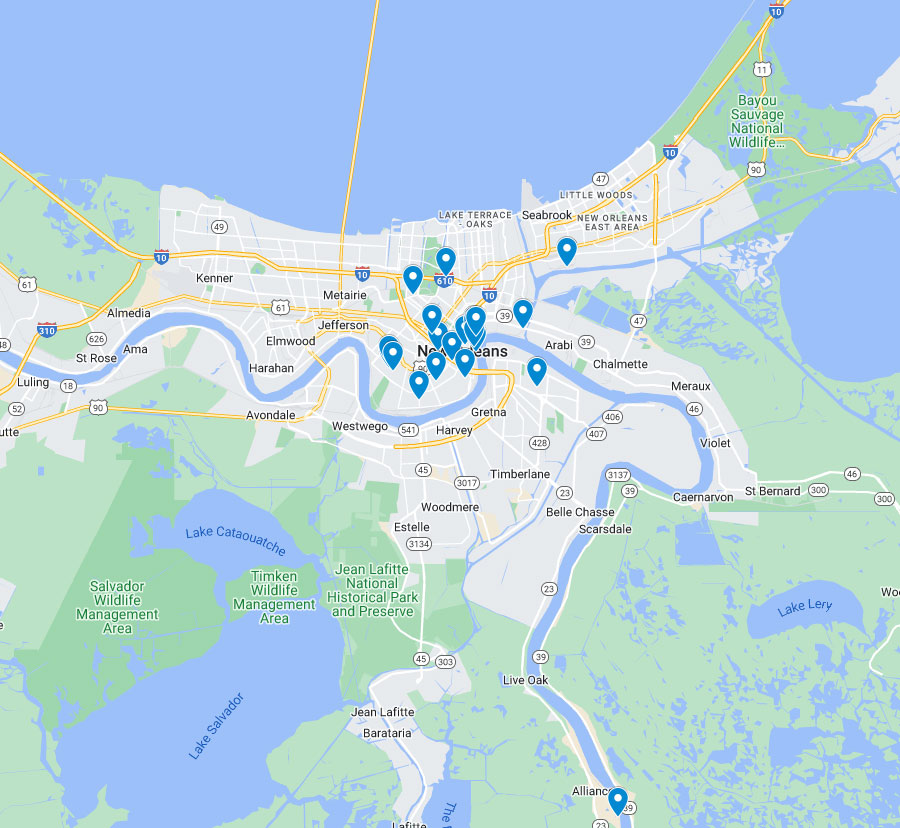

My Monroe Fellowship gave me the opportunity to carry out research on Edgar Degas’s two paintings of a New Orleans cotton office, produced during his 5-month stay in the city in 1872-73. I analyze his two pictures as explorations of the multiple ways that Southern cotton had revolutionized the world of European textiles and re-shaped the quotidian material environments of 19th-century Parisians. Indeed, cotton grown in the South – a significant amount of which passed through the port of New Orleans and which was central to the economy of the city – constituted a substantial portion of the raw material that ended up as a wide range of cotton fabrics in Europe, affecting everything from what people wore to how they decorated their homes to the kinds of paper they used. Degas, I argue, had a deep and sustained fascination with the material make-up of everyday environments and, in particular, with fabrics, producing countless pictures over the course of his long career of different kinds of clothing and costumes, bedding, towels, fabric workers of various kinds, and so on. Degas was also keenly interested in the materiality of his own works, constantly experimenting with different kinds of media and supports. Thus, I argue that Degas’s two cotton office pictures constitute the artist’s recognition of the important role that Southern cotton played both in his body of work – from his many images of fabric-filled interiors to the very paper on which those images were produced – and in the physical make-up of many Parisians’ everyday surroundings.