Biography

Christina LeBlanc is a History Ph.D. candidate at Tulane University studying US federal disaster relief in Puerto Rico from 1928-1960. Her dissertation examines how political status and gender shape US federal disaster relief in Puerto Rico during the mid-twentieth century. In 2019, she worked for Congresswoman Lucille Roybal-Allard (CA-40) as a Women's Congressional Policy Institute Legislative Fellow on environmental, public health, maternal health, foreign policy, and animal rights issues. She has worked as a Marketing and Communications Manager with Tierra Resources, a startup focused on restoring and protecting coastal wetlands in Louisiana and across the globe. Prior to this, Christina was an Americorps VISTA with Global Green working on residential energy efficiency in New Orleans, LA. She holds a B.A. in Diplomacy and World Affairs from Occidental College and M.A.’s in History and in Latin American Studies from Tulane University.

Research

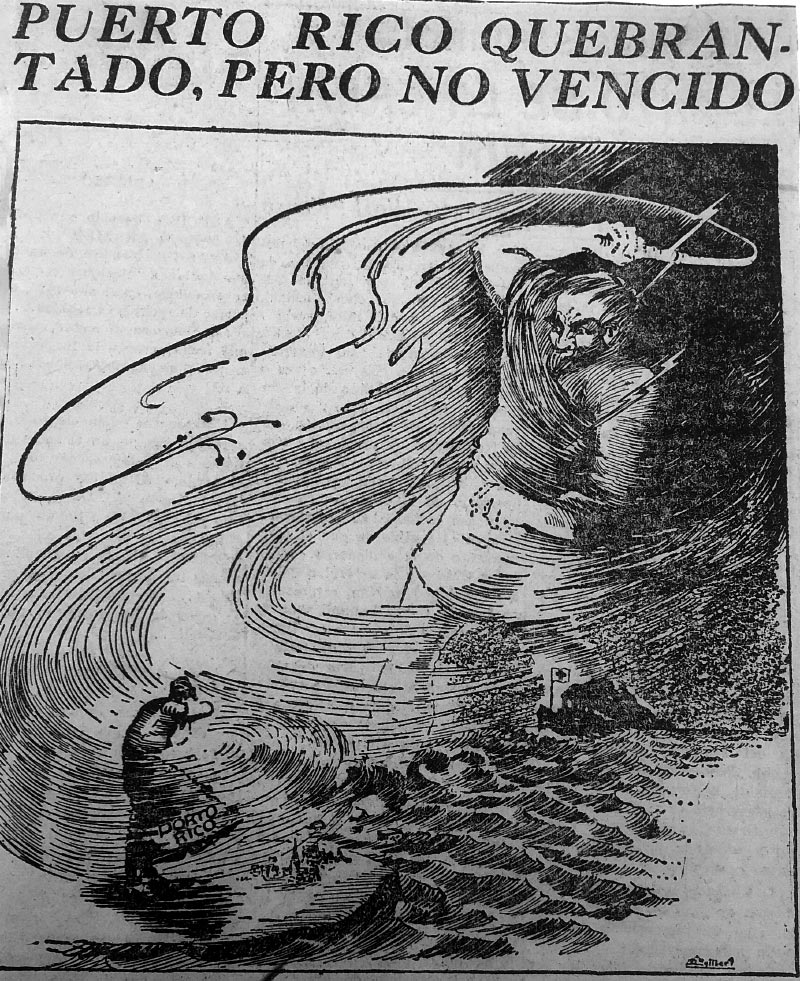

Entitled After the Storm: Disaster and Development in Puerto Rico, 1928-1960, my dissertation examines disaster relief in Puerto Rico to explore how the political status of Puerto Ricans influenced the distribution and allocation of aid on the island. As both citizens of the United States, though without full representational rights, and as racialized others, Puerto Ricans were often seen as "foreign in a domestic sense,” by the U.S. bureaucrats overseeing federal disaster aid. Puerto Rican politicians, farmers, community leaders, nurses, and professors all advocated for their rights as citizens in these moments of recovery and change. Like in Louisiana and across the Gulf South, the lore surrounding hurricanes, flooding, and the long recovery process in Puerto Rico influenced the culture and expectations of citizenship on the island. This common experience binds the coastal south with its Caribbean neighbors both environmentally and culturally. There is much to be learned by including Puerto Rico within the environmental historiography of the Gulf South. My dissertation tells the history of Hurricane Maria by examining choices made by politicians in Washington, D.C. and San Juan, movements led by housewives and nurses, and struggles by Puerto Ricans of every class, race, and religion to define and claim their understanding of rights as citizens. This also opens up possibilities for transregional, multicultural, and multilingual understandings of the bioregion of the Gulf South and pushes us to constantly question the borders, boundaries, and limits we place upon understanding the region’s history and culture.