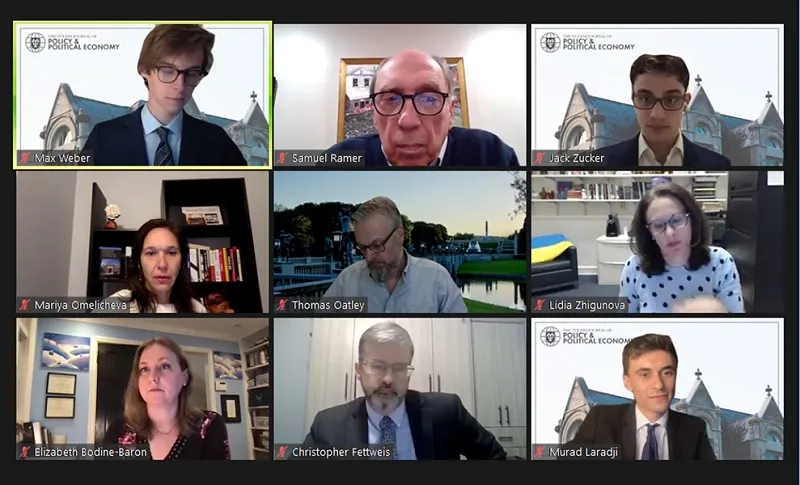

The Tulane Journal of Policy and Political Economy (TJPPE), hosted a panel on March 10, featuring experts in international relations, national security, history, political economy and Slavic studies to discuss the Russian invasion of Ukraine. The six-member panel spoke to the reasons for poor performance of the Russian army, the effects of sanctions, protests in Russia and the potential for nuclear, biological, chemical and cyber-attacks, as well as Vladimir Putin and Russia’s connection with the orthodox church.

Lidia Zhigunova, a professor of practice in German and Russian studies at Tulane University says, “Since the beginning of this war the question on everyone’s mind is why Putin is doing this, why did he start this needless senseless war?” She says Putin addressed the Russian nation a few days before the war. “He argued that Ukraine in fact is not a real country, it was created by soviet Russia. He said it’s an invented country, an extension of Russia, a country which is now hijacked by the west and run by the neo-Nazis.” Zhigunova says Putin claims the invasion is for the denazification of Ukraine and that the Ukrainian people need to be rescued or liberated from a government that is run by neo-Nazis and is holding its people hostage. She says these same types of white supremacist radical groups found in Ukraine are also in the U.S. and many other countries including Russia, but they are not running the country. “It’s far from it," Zhigunova says, "the data from the 2019 elections in Ukraine show that the ultranationalist far right coalition gained slightly over two percent of the vote and zero seats in the parliament.”

As for Ukraine not being a real country, in a follow up with Samuel Ramer, an associate professor of history at Tulane, he says "We see a Ukrainian national consciousness developing at the end of 19th and beginning of the 20th century. And on the eve of the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 every district within the Ukrainian republic, even those heavily populated by ethnic Russians, voted for independence. It was on the basis of this kind of overwhelming vote that Ukraine became a sovereign state." Now 30 years later, says Ramer, “It’s undergone an evolution in which that population has a acquired a much more profound western consciousness and as one commentator put it – ‘we may be screwed up but we are free.’ And that freedom, which I won’t characterize as a political structure but it’s a sort of atmosphere,” says Ramer, “that is the only thing I can see is really troubling in terms of Russia’s security interests.”

When asked if the Russian invasion of Ukraine might be leading to a new age of militarization, or a so-called 21st century cold war, Tulane professor of political science, Christopher Fettweis, says, he doubts it. He believes rather than a first action in a new rivalry, this may be one of the last actions in the old rivalry – “an extension of the first cold war.” “Putin and his cronies are essentially soviets, totalitarian, at least in their aspirations, as the people who led them in the 80s.” Fettweis says, “It may be that in a couple of decades, historians look back on this and say this was one of the last actions in first cold war.” Fettweis says the attack on Ukraine has been a massive intelligence failure by Russia. “It’s been the kind of thing that the soviets would do a lot during the cold war, and it’s just another sign that this is essentially a soviet regime.” He says from a security perspective also, they are Soviet in their ways of war. The modus operandi is to “surround cities with artillery and blast them into oblivion.” Fettweis says tactically speaking, at the start of this war it looked like they were going to try something different, a bit more 21st century, but "they failed entirely." He says Putin’s next step is likely a siege of Kiev that will look a lot like a siege seen in medieval times.

“What this (war) means more generally to the international system,” says Thomas Oatley, “I think what we are seeing is a really fundamentally pivotal moment in post WWII and post-cold war order. I think that there is no going back to where we were in this global order three weeks ago. The world has changed irrevocably.” Oatley, a professor of political science and Corasaniti-Zondorak Chair in International Relations at Tulane, says this act has begun to fracture the international system and he sees the possibility of Russia aligning with potentially China and Brazil along with lower income societies against a bloc of U.S. and western European countries. He says this conflict is about more than just Ukraine. “I think this conflict is really about his (Putin’s) attempt to destroy the post-war order as a necessary step of reasserting Russian great power status in the international system. Because there is no possibility for Putin or Russia to be a great power in an Anglo or an American-led international system.”

This is Putin’s fifth war since he came to power in the year 2000, and Zhigunova says “all of these wars were fought with the same brutality, bombing the cities, destroying the infrastructure, not just the military infrastructure but targeting apartment buildings, hospitals and schools. Not being particularly concerned about the loss of human life on both sides.”

Putin’s army has already committed atrocities that experts say constitute war crimes, but proving and prosecuting these crimes can be very difficult says Mariya Omelicheva, professor of strategy at National War College. She says it’s not enough to just collect evidence, which the Ukrainians are doing very well, but prosecutors need to “establish the command and control that the orders came from the president,” and “based on the history of these kinds of trials, …, it’s just been very very difficult to establish this line of command with certainty.” She also says to convict Vladimir Putin as a sitting head of state would be even more challenging as it would require a regime change. Investigations into war crimes committed by Putin have already been launched by the International Criminal Court as well as the courts of Germany and Spain. Omelicheva says, “It’s going to be very difficult to convict the perpetrators, but it shouldn’t stop these judicial bodies from seeking to prosecute these war criminals.”

There were protests in Russia at the start of the war and thousands of people were arrested. Putin has since isolated the Russian people from the rest of the world by cutting off independent media within Russia and access to media from outside Russia. Elizabeth Bodine-Baron, a senior information scientist at the RAND Corporation, says the Russian people are “living in a different information space and not willing to believe what their family members in Ukraine are suffering.” Though she says, this may change as more bodies of Russian soldiers are brought back across the border in body bags. She says “Russian mothers and grandmothers are a powerful force and so this is a potential target audience for messaging that could be brought to bear.” Though a majority of Russians may be in the dark about what’s going on, Bodine-Baron says the Ukrainians have been very adept at crafting a media narrative directed toward western audiences – Europeans and Americans. “And a lot of what they’ve put together has contributed to the groundswell of support,” she says.

Zhigunova says that since the start of the war, Ukraine has changed dramatically, becoming more unified and united like never before in the country's history. "Ukrainians, Russians, Jews and members of other ethnicities all joined together to defend their country," she says, "Putin sought to destroy Ukrainian identity, but he actually solidified it." Zhigunova says, “I think after this war, Ukraine, Russia and the entire world will not be the same.”

View the recorded discussion at https://www.tulanejournal.org/russianempire.