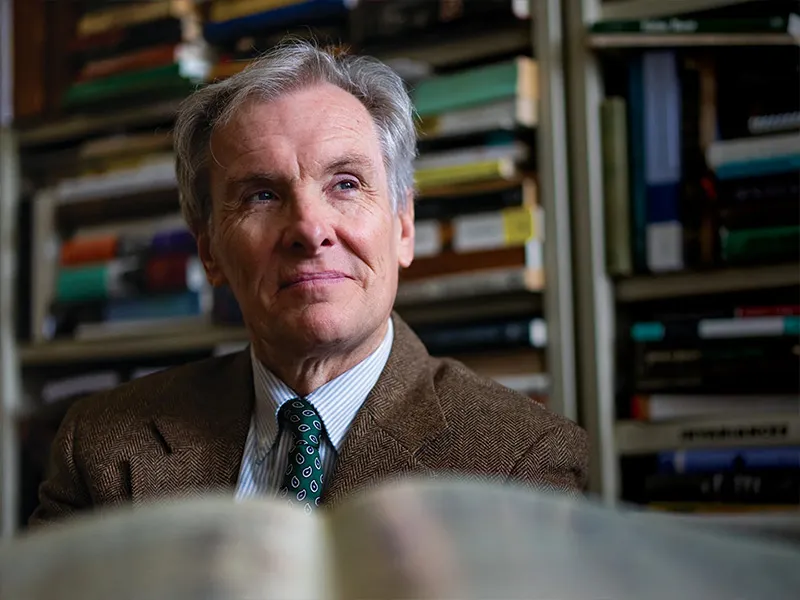

Michael P. Kuczynski, Pierce Butler Professor of English

Originally published in the 2025 issue of the School of Liberal Arts Magazine

When I was an undergraduate in the late 1970s at a small Jesuit college outside Philadelphia, earning your BA was like getting on the elevated train at the first stop and not disembarking until the last. Study was organized around a humanities “core”: two courses in prose composition (at Tulane, we call this First-Year Writing), three in History, three in Philosophy, three in Theology, and three in foreign languages. Because I was an English major, there were numerous additional requirements in literature, historically arranged, from Chaucer through modern poetry. I was already intrigued by the Middle Ages and interested in becoming a medievalist, so I chose Latin for my language. The rest of the core set me up wonderfully for graduate school.

When I got to grad school, I sometimes found myself ahead of my peers because of my undergraduate training. I didn’t have many graduate electives, but that didn’t bother me. After all, I had elected — as a graduate student now — to continue working the core. The microchoices of my education were laid out before me, like a chef’s tasting menu. None of them were bland.

Most colleges and universities no longer offer this kind of core curriculum to either undergraduates or graduate students. I think, however, that the concept of a humanities core and its availability at a place like Tulane makes sense. Tulane combines the appeal of a Research 1 institution with a liberal arts college. Working the core, for faculty and students alike, enhances both those missions.

Proponents of AI in higher education, beware!

For many excellent reasons, students want more choices, especially across the undergraduate curriculum — and the core appears to restrict choice. The original core was popular at Columbia University after World War I, as a way of ensuring that all students received a basic grounding in what were regarded as the “classics” of Western thought and writing. The names of core authors are inscribed around the outside of Butler Library, a site of student activism since the 1960s. The marble lineup is exclusively male and Eurocentric. I once heard someone refer to it cynically as a tombstone. I’d argue, however, that working the core for many years has in fact enlivened and strengthened it: Certain muscles that the corpus of American education never knew it had, have become manifest. During the 19th century, figures such as Ralph Waldo Emerson, Margaret Fuller, and Henry David Thoreau, whose educational programs were steeped in Latin and Greek, also advocated for the study of modern Western languages and literature — and for the editing, translation, analysis, and emulation of various Eastern texts, such as the Bhagavad Gita. That rebel Thoreau demonstrates, throughout Walden, how the discipline of studying classical languages is liberating rather than confining. In Columbia’s core today, Toni Morrison stands alongside Homer, Gandhi accompanies Plato, and Andy Warhol hangs with Raphael. What is required in the 2020s is more representative and various than in the early 1900s, in part because the original core stimulated the intelligence of those who submitted to it and encouraged a critical examination of the concept of “value.”

The other day, I was reflecting on how, in each of my core classes as an undergraduate, two figures were mentioned so regularly that they might have been enrolled as my fellow students: Freud and Marx. I am neither a Freudian nor a Marxist, but I learned an immense amount from hearing my professors — some Jesuits, others lay people — apply the ideas of these two monumental thinkers to the interpretation of literary texts. I never felt, in reading them, or Milton, or Thomas Aquinas, that I was being “indoctrinated.” I remember in particular reading a short book, Hamlet and Oedipus, first published in 1949 by a disciple of Freud, Ernst Jones. I’d obsessed over these core dramas before, but never thought of them together. Jones’s approach changed my imaginative engagement with Shakespeare and Sophocles for the better. I also remember reading Hard Times, Dickens’s novel about industrialized education, in the same class in which I read an abridged version of Marx’s masterpiece, Capital, and the full text of Darwin’s Origin of Species. At the end of the course, I was an avid student of fiction alongside nonfiction, and vice versa. My education in the core had helped me to escape the mechanical approach to life and learning that is encouraged at the corporate school in Hard Times — run by Mr. Gradgrind and supervised by his master teacher, Mr. M’Choakumchild. Proponents of AI in higher education, beware!

Some teachers and students of the core were undoubtedly more elitist and exclusivist than others. But for those of us who worked the core properly — in both a disciplined and enlightened way — its boundaries also became vistas. I am currently writing a book entitled White Jesus, about how one of the most influential figures in human history, an itinerant Middle Eastern preacher, became Europeanized during the medieval and early modern periods, in literature, theology, and the visual arts. I would not have been able to imagine such a book, let alone write it, without my training in the core. Working the classical core enabled me, as it has many others, to look imaginatively beyond it.

Michael Kuczynski is the Pierce Butler Chair and professor of English. He specializes in Middle English literature (especially Chaucer), intersections between religion and literature in medieval and early modern England, and the relationship between poetry and the visual arts. Kuczynski was elected to the council of the prestigious Early English Text Society, only the third American ever elected to the leadership position. Kuczynski, along with Professor John “Ray” Proctor, received a grant from the Folger Shakespeare Library to develop a scholarly program examining the intersection of race and Shakespearean research and performance in the Southern United States.