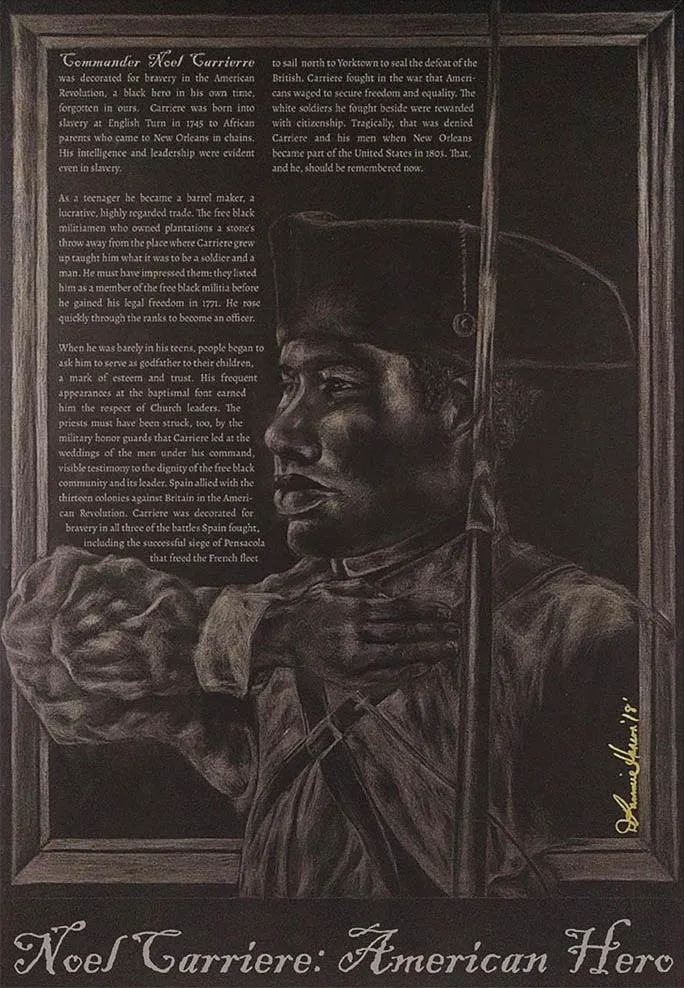

Most Americans don’t know that Louisiana fought in the American Revolution on the side of the thirteen British mainland colonies. Only a handful know that one of the soldiers from Spanish colonial Louisiana who helped win America’s freedom was a man named Noel Carrière, the commander of the New Orleans free black militia.

The absence of Louisiana and Carrière from most versions of America’s founding story highlights one the great paradoxes embodied by New Orleans. In the popular imagination, the city is unique, unlike any other in the U.S.—an exotic, exceptional place that sits outside the parameters of what is typically American, past and present. This is the city that is promoted to tourists and, if truth be told, to prospective Tulane students. The New Orleans waiting to be discovered in the city’s archives, however, is quintessentially American, right down to the role it played in the nation’s birth. If you don’t know that this story and its heroes are there to be found, though, you’re unlikely to go looking for them. Even if you’re a historian. And even if you are a historian and intrigued by that prospect, in order to find them you have to be able to read the French and Spanish documents that reveal the city’s history.

The majority of American Revolution historians have not found themselves on this path. And although I can and do read French and Spanish, I have to confess that I did not go looking for Carrière. I stumbled over him. In the course of a quarter of a century in New Orleans archives spent chasing down the histories of colonial nuns and free people of color, I kept coming across his name. He flitted in and out of the archives like a moth, indistinct and elusive, but persistent. About ten years ago, I realized that I had enough archival fragments to trace him from his birth in slavery in the 1740s to his death in 1804. It’s rare to be able to do that, since the records that fill America’s archives were produced by Europeans and their descendants who were eager to tell their stories but mentioned Africans and African-descended people only in passing, if at all. That was especially true of those born into slavery, like Carrière.

Yet there he was in the archives, again and again. The priests of St. Louis Cathedral recorded him as the godfather and namesake of many enslaved and free infants and adults who shared his African ancestry. Those same priests wrote him into the historical record as an honored witness at the marriages of men who served under him in Louisiana’s free black militia. New Orleans notaries included him in the inventories of those who claimed him as a slave, recorded his sale to new owners and, finally, inscribed his name on the document that verified his purchase of himself, an act that made him legally free. Another priest documented his marriage, and yet another his burial. A census revealed that he was a barrel maker, and an act of sale revealed that he owned a home and a workshop in New Orleans. Other acts of sale chronicle his purchase of other human beings to labor for him, a sobering, confusing discovery. Spanish governors listed him on the rolls of the free black militia and twice nominated him for medals and monetary rewards for his valor in battles of the American Revolution.

As the bits and pieces from the archives piled up and I worked to make sense of them, I realized that Carrière epitomized many of the things that made America, America. He pulled himself up from nothing. He was a devoted husband and father who worked hard so that he could leave enough to his children to provide them with the security his own father, captured in Africa and enslaved in Louisiana, could not give to him. He fought bravely in the war that granted America independence and promised its people freedom. And, like so many economically successful American men of his time, he bought the bodies of others to serve him. One of the great ironies embodied by America’s founders was their invocation of liberty even as they held others in bondage. In this, sadly, Carrière was no different from Thomas Jefferson.

In other ways, Carrière could not have been more different. His father came to New Orleans in the hold of a slave ship as a small, terrified child taken captive in the chaos that followed the fall of the African kingdom of Ouidah. The African-born commander of the Louisiana free black militia who taught Noel the arts of war initiated him into the great military tradition of the ceddo warriors of Senegambia. The most important people in Noel Carrière’s life, the people who taught him how to be a man, a husband, a father and a soldier, were Africans. He was an American Revolutionary War hero, but he joined that fight as much as a son of Africa as a son of America.

Noel Carrière was a global American founder, a figure who embodies the intersection of New Orleans with the U.S. and the wider world. He was worth looking for.

Clark’s book, Noel Carrière’s Liberty: From Slave to Soldier in Colonial New Orleans, is expected to be in print in early 2021.