Originally published in the Summer 2022 School of Liberal Arts Magazine

Monday, August 15th, 2022

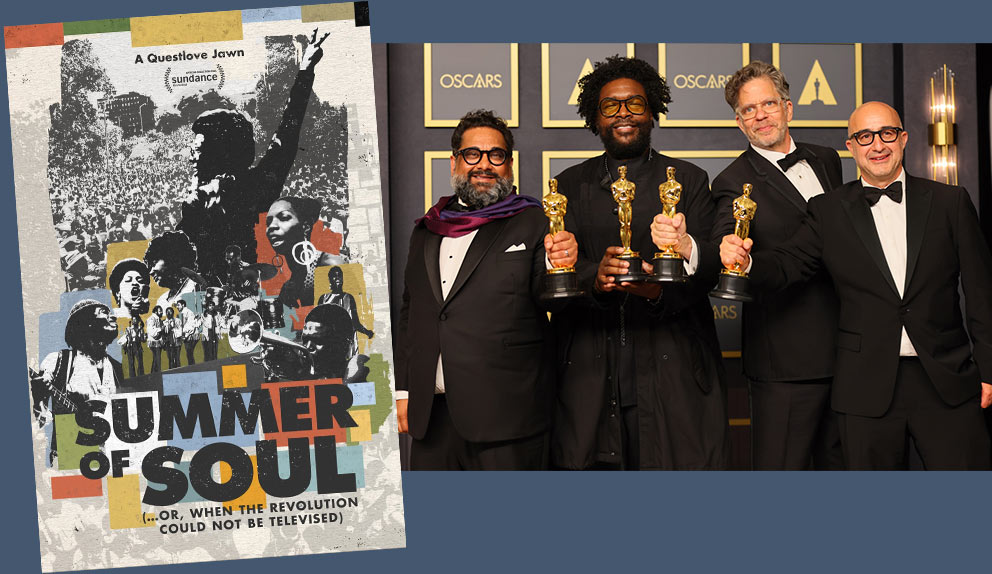

An interview with 2022 Academy Award-winning producer Robert Fyvolent (A&S ’84)‚ whose dynamic educational and professional pursuits brought him to this year's Best Documentary Film project and our School of Liberal Arts Distinguished Alumni Award.

Robert Fyvolent graduated from Tulane in 1984 with a BA in political science. Following law school and a career on the legal side of the film industry, he recently came to wide recognition for his role producing the documentary Summer of Soul (…Or, When the Revolution Could Not Be Televised). The found-footage love letter to the 1969 Harlem Cultural Festival swept the 2022 awards circuit, culminating in both the Best Documentary Oscar and Best Music Film Grammy. Replete with performance videos and voiceover from icons like Mavis Staples and Stevie Wonder, the film was also the directorial debut of Ahmir "Questlove" Thompson, drummer and joint frontman for The Roots—a debut Fyvolent himself made happen along with producing partners David Dinerstein and Joseph Patel.

Filmed with a multi-camera crew by television veteran Hal Tulchin, the footage seen in Summer of Soul was shelved for decades before Fyvolent heard about it from a friend. The entertainment lawyer and former studio executive approached Tulchin in 2006, and ultimately teamed with the others to hire director Questlove and, together, produce the film. At the School of Liberal Arts diploma ceremony on May 20, 2022, Dean Brian Edwards presented Fyvolent with the Distinguished Alumni Award. Here, he sits down with Juliana Argentino, Director of Marketing & Communications, in a conversation about his path from Tulane to the Oscars.

Juliana Argentino (JA): So, as a starting point for readers, let’s say they missed the awards circuit this year and have never heard of Summer of Soul. Give me your lawyer-turned-producer explanation of how you came to be a part of this music documentary and its huge success.

Robert Fyvolent (RF): I always had an interest in working on the creative side of the industry. I graduated from South Texas College of Law but completed my legal education at Loyola Law School in Los Angeles. I also spent one summer at NYU Tisch Film School, in their intensive film certificate program. So it’s safe to say I always looked at getting into the entertainment business as a lawyer, to learn and get my foothold in the business. And then it became a bigger part of my career throughout those early years via other things I did on the creative side. Years ago, I entered a screenwriting contest, and I won, which inspired me to write a movie—that did actually get made—called Untraceable, starring Diane Lane. Seeing a movie get produced was big for me, and it led to other writing jobs. From there I sold some scripts that weren’t ultimately produced, but I kept my hand on both sides of the industry and Summer of Soul was born out of my legal work, really.

“My musical education came from my experience living in New Orleans, and similarly, my academic interests—and eventually my study of the law—helped me recognize the importance of using the Harlem Cultural Festival music and footage to tell this story about lost history and the fight for civil rights.”

— Robert Fyvolent

JA: How so?

RF: I was approached by a friend who was working on a music doc of his own, who started asking me about music clearances, and once I started learning about this festival in Harlem, I had to know more. I flew to New York to find Hal, who was at the time in his 80s and had all this footage that he had shot in 1969 himself—in his basement! And he had high hopes for it, originally, but then ultimately none of the networks were interested in it. There has been a lot of speculation as to why, but there are some obvious reasons; there were three major television networks at the time, and these were for the most part, African American artists. And so nobody picked it up. He held onto it and from time to time would explore doing something with it, start to transfer it to digital but then stop, or just change his mind entirely and pull back, but when I got involved with it, even though I didn't have any producing credits, I was really passionate about the material, and I managed to convince him to let me do something.

JA: And now here we are. But it wasn’t exactly a quick or direct road to get to this point, was it?

RF: 15 years! It took a long time and there were other times it came close, but I’m so thankful it never got made then. I think this version of it—with the director we had, the timing in the country, and even the pandemic to some extent, because I think people were hungry for a communal experience—came together because it was the right time and the right place. This movie delivers a joyous, cathartic music experience and I think the combination of all those things really made it what it was.

JA: Was the experience of making it as joyous and cathartic? Filmmaking is obviously a collaborative process, but what was it like to be in the driver’s seat with such precious material?

RF: One of the roles of a producer is to build that collaborative team, and when my client-turned-friend David (Dinerstein) and I began collaborating, we quickly realized Ahmir Questlove Thompson was the right person to tell, and direct, this story. As music fans and fans of the Roots—we’d even seen them together once—getting him on board was really the start of putting this version together. We also knew that as a first-time director we needed to build a strong team around him, so we targeted a specific editor, who was also a musician, knowing that would make for a good work in collaboration with Questlove, who professionally is a musician first.

JA: And also one of the more recognizable late-night performers on one of the aforementioned big three networks…

RF: Yes, we did think about the fact that he has a nightly platform that reaches a broad audience. Not just people of the age group that would appreciate some of these artists from when they were young, but younger people who sort of bridge that gap, in a sense, and so that was another reason why we thought he was perfect for it. He was hesitant at first, given he’d never directed, but then he saw the footage, and especially for somebody who considers himself a music historian—obsessed with music history—it was hard for Ahmir to turn it down.

We partnered with Radical Media, literally blocks from where he was living; even though we’re based in L.A., we wanted the production based in New York. Of course, we didn’t know the pandemic would hit us in the middle of it, so that made our ability to be there for a lot of in-person parts difficult, but it also just became that it didn’t matter where anyone was. We were all just spread out, pulling this all together from our homes across the country.

JA: Definitely a unique experience. But, on the other side of that, was the fact that you were all working with found footage helpful?

RF: We set out with the mindset that we were not just going to make a music concert film, we wanted it to be a movie about that era—really about the festival itself and why this footage was sort of lost, and that larger history. But the pandemic made it harder because of all the elderly people we wanted to interview who we couldn’t, due to heightened health risks. Some had participated in the festival, like Gladys Knight and Mavis Staples, and then even people not directly associated who we knew would be good subjects but were unavailable due to the risks.

Essentially, it all got much trickier, so we had to dig deeper into archives to supplement the movie with more context, which I actually think really helped the story. It’s weird to say the pandemic made the movie better but I think on some level it did, and ultimately, we got most of those interviews anyway, in some cases audio interviews instead of filmed interviews—which we incorporated as voiceovers with the archive footage.

JA: Summer of Soul is about a music festival in Harlem, but obviously it’s hard to ignore the connection between music out of that area at that time with music coming out of New Orleans. Do you attribute your immediate need to learn more about this festival to the love of similar music you developed while in school here?

RF: Oh absolutely. One of the most impactful moments of the film is when Mavis Staples sings with her idol—the only time it ever happened in her life—gospel star Mahalia Jackson, who had a huge presence in New Orleans and in Jazz Fest history. I grew up in Tampa listening to Led Zeppelin, Aerosmith and those iconic 70s bands my peer group was listening to. I had a curiosity for other kinds of music, but it wasn’t until I got to New Orleans that my real music education started, and I expanded my interest in a much broader way than I could have if I went on to the University of Florida.

JA: Did it feel like a clear path from lawyer to award-winning film producer?

RF: In my role with Summer of Soul, I did bring my legal background to a project where, as you can imagine, there were an unbelievable number of rights. Amir and our third producer Joseph Patel were sort of in the trenches day-to-day going through things, but we would all get on Zoom calls and talk about which segments we were going to use, where those segments are going to be, how the story was going to work and all of that. But beyond that element, I was not a hands-off producer, where I said here’s the material, when can I buy my popcorn, you know? Both David and I were very involved throughout the process even though we worked remotely in Los Angeles during the pandemic.

We took a very deep approach to how we were going to sell this movie because our strategy from the beginning was nontraditional. Our idea was to make the movie we want—without any interference—and then take it to a festival and find the best buyer. We ended up with the distributor we wanted in Disney, and we insisted that they, at a time when theaters were shuttered, commit to releasing it in theaters. I do think it helped me to have the legal and studio experience in my role here as a producer, to ensure we got the right outcome there.

JA: Has this last year changed how you’ll split up your time between your work as a lawyer and creative or production work?

RF: People ask why I’m still practicing law because I could be producing full time, and I may end up there, but I do enjoy law. It’s harder on some levels than producing; as a lawyer, I have all kinds of ethical considerations, and I have a responsibility to other people where I need to deliver within a set window. Whereas on the producing side, this project has been ongoing for 15 years—and I don’t have another 15 years in me for something like this. So I may slowly make that transition, and I’m about to go to work on some new projects, but for the time being, I’m still a mix of both.

JA: I do think the liberal arts represent that kind of left and right brain dynamic, and that getting to move both sides forward is what maintains both balance and interest.

RF: Sure, and a growing number of people question whether a liberal arts education is worth anything or say you’re better off learning a trade in terms of making a living. I would say I’m a big believer, as a lawyer, in critical thinking, and I think no matter what classes you take or what you study, college gives you a framework to apply critical thinking, even on a class-by-class basis, regardless of the subject and even if it’s not something that you end up pursuing. You take a sociology class, and you don’t end up working in sociology, but you still had to work through that course to understand those issues. It gave you a perspective of the world, and that will help you in some way in whatever it is you’re doing.

JA: Tell me about a class at Tulane that made a particular impression on you.

RF: I did really like my political science professors, but I had one unique professor outside of that department, someone everyone considered to be a bit unconventional—he was this older, opinionated Southern guy—and perceived as an easy grade, but he was fascinating. The class was called “Psychology of Aesthetics” and it was all about how art and music impact the collective psychology of communities, and at the end we had to bring in a piece of art that we wanted the class to discuss. I brought in something I expected him to have no connection to, or to hate: a recording of “The Message” from Grandmaster Flash. I played it and everyone in the class was wondering what I was thinking, because for a while he was just not giving any reaction, but then he loved it! And it was just one of those great moments of connection and conversation that stayed with me. I am very sure it was the first time this professor had heard any sort of rap music and it was interesting to me that his impression, true to the class, was based purely on aesthetics and not on what anyone might have anticipated given his unfamiliarity with that art form and culture. I feel like it was a lesson about music being able to break down walls.

JA: Finally—you won a lot of awards this year, but we got to cap it off with your Distinguished Alumni Award and your speech at our commencement ceremony. What was it like to come back and speak to these graduates for you?

RF: It was truly an amazing experience. The entire journey has been a bit surreal. The movie was really a labor of love and to have it succeed the way it did was beyond anything I could have imagined. I felt the same way about coming back to Tulane to share that Commencement moment with students. I’m so grateful to the School for honoring me and allowing me to share my experience with graduates. I received a lot of positive feedback from students afterwards, and it was really a prideful moment—a validation of my studies at the school.