Graduate school is a deep dive into scholarly work. When we consider a graduate education, we often picture a researcher digging through the archives, working in a lab into the night, or writing for hours upon hours. For the past five years, the School of Liberal Arts has been offering graduate students a signature initiative that both enriches and complicates their graduate experiences, balancing the private aspects of academic work and their public impact. The Tulane Mellon Graduate Program in Community-Engaged Scholarship has supported sixty graduate students from a wide range of disciplines who use the program to connect their graduate studies to community organizations in New Orleans and around the world, challenging the notion of a solo researcher as paramount to academic success.

The Mellon Graduate Program draws on the experience of Tulane’s faculty, as well as on the wisdom of community leaders. Each year, a dozen graduate students join a cohort with four faculty members with experience in community engagement and four leaders of cultural and activist organizations. These cohorts meet regularly for two years and work to use their academic research in support of real-world change, from enhancing education and uplifting environmental and housing concerns to bridging access to technology. The work of Mellon fellows exemplifies the essential elements of a graduate education of the future rooted in engagement with one’s surroundings.

Maura Sullivan

Linguistics Doctoral Student

“Together, Mellon fellows develop as a community and interact not just as academics or professionals, but as whole people in all of their complexity,” said Ryan McBride, Administrative Associate Professor and Mellon Program Director. “The program strives to interrupt the traditional power dynamics of academia, apply decolonizing methodologies, and practice the kinds of critical introspection necessary for ethical community-engaged scholarship.”

Building an interdisciplinary community with their cohort gives Mellon graduate students experience discussing their research with people from outside their disciplines, as well as outside academia. The cohort conversations also help graduate students reflect on the research practices of their home disciplines and on the complexities of bridging their academic work with public arts and humanities projects. As Maura Sullivan, a linguistics doctoral student, stresses, this process addresses an important question facing many academics today: whom is my research really serving? Sullivan is from the Coastal Band of the Chumash Nation, located in what is recognized today as southern coastal California. As a Native scholar, she is both a member of a community and a researcher of that community. “I am constantly revisiting my research to make sure it not only benefits my community, but embodies a research ethic,” explains Sullivan, who has witnessed extractive practices of academics in Native communities, both her own and others.

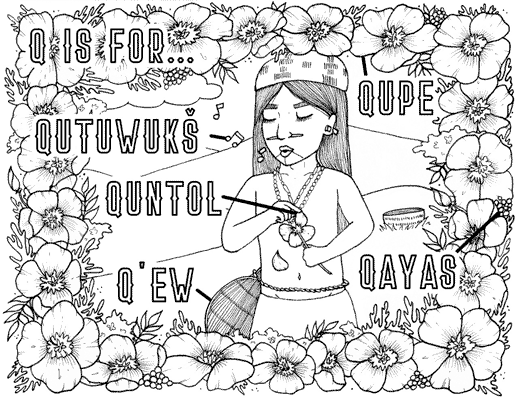

Putting her research into practice, Sullivan has been working with the Chumash Nation to diagnose the community’s Native language use and develop a coloring book with Indigenous artist Solange Aguilar for the Chumash youth to aid in language revitalization. With the guidance of Judith Maxwell, professor in the Department of Anthropology, Sullivan is working closely with her Native community to bring their language back to daily use, which is a vital part of preserving their culture and history. Her graduate research and Mellon Program work is rooted in reciprocal exchange, and in order to support this exchange, she places a primary emphasis on community and collaboration.

Lilian Lombera

Latin American Studies Masters Student

These principals also echo throughout the research and work of Lilian Lombera, a Mellon fellow completing her master’s degree in Latin American studies. “It is essential that we are open to the idea that knowledge exchange is reciprocal. Working with communities in a nonhierarchical approach is a great way to learn and practice this, and I believe arts are a door to become aware of a community,” explains Lombera. Lombera’s research—which is based on her work as a cultural producer for many years in Cuba before coming to Tulane—explores how cultural exchanges between regions can bring awareness to social issues. Similar to Sullivan, she is also researching the communities of which she is a member. Lombera’s work brings together her previous work and uncovers a dialogue between the Cuban band Cimafunk and the cultural practices of Queen Cherice Harrison-Nelson and the Guardians of the Flame Maroon Society in New Orleans. Working specifically with artists and culture bearers that are honoring maroons—individuals who escaped from slavery and created their own communities—Lombera amplifies the voices of her community members to reiterate the importance of learning from those in our communities that are often not considered teachers. In her words, she works to “empower communities through decolonizing experiences,” and while she works with living artists, a large part of her work is focused on how we document culture and how this affects which voices are represented throughout history.

Diana Soto-Olson

Mellon Graduate Program Manager

Lombera’s Mellon Program project has been bridging the intersections of community, language, and cultural production through two iterations. In March 2020, she worked in collaboration with Horns to Havana, the Trombone Shorty Foundation (TSF), Gia Prima Foundation, and Cuban Educational Travel to create a cultural exchange between New Orleans students from the TSF and Cuban students from Amadeo Roldan music conservatory. For the first time, musicians Troy Andrews, Soul Rebels Brass Brand, and Tank and the Bangas, and cultural ambassadors Harrison-Nelson and Big Chief Monk Boudreaux traveled to Cuba to participate in a cultural exchange called Getting Funky in Havana, during which they created music together with Cuban students in an experiential, learning environment. As the Covid-19 pandemic stretched across every region of the world, Lombera shifted her attention to working with director Catherine Murphy on Maestras Voluntarias, a film focused on how community education in the early 60s can inform and inspire individuals today.

Mellon Graduate Program Manager Diana Soto-Olson explains, “The Mellon Program’s community of scholars and cultural leaders is a home for many and the exciting work they do together makes our graduate program in public humanities unlike any other.” Both Lombera and Sullivan are not just documenting the work of often-overlooked culture bearers; they are collaborating with them and developing their scholarly approaches in tandem, expanding the role academics and universities play in responsibly recording history through community engagement. From California to Cuba, Sullivan and Lombera’s work with their communities enriches their home disciplines, produces scholarship for academics and the larger world, and transforms their graduate education experience at Tulane University.