In October 2009, I traveled to Pordenone, Italy near Venice to attend an eight day international festival for silent cinema historians, archivists, curators, critics, and local enthusiasts. The 28th Pordenone Silent Film Festival included films from archives around the world and featured many newly restored prints with original tinting and toning effects as the festival's poster of Mae Murray in The Merry Widow (Stroheim, 1925) suggests. Every film screened was accompanied by live music ranging from a single pianist to a full orchestra and films were shown continuously from nine in the morning until midnight in the modern Teatro Verdi in the center of the town. Pordenone proves the point I make with my students that "silent" cinema was neither silent nor black and white (and certainly not boring).

Viewing these films in the manner in which they were once experienced—as spectacular events with sound and image and color—brings them to life as a cultural experience that is both a mnemonic of past cinematic practices and a contemporary expression of intelligent cinephilia. As a silent cinema scholar, I frequently view the objects of my research on the twelve-inch viewing monitor of a flatbed editing suite in an archive. If I am lucky and the films exist on DVD, I can study them on a computer screen or a television monitor. At Pordenone, I have the opportunity to experience films that I know about but have never seen projected on a large screen and to learn about films buried in the archive that I never knew existed. The ability to see a large number of films in one place in a short span of time is equivalent to years of searching in archives where often, in the first instance, the only thing you have to go by is a title or cursory description in a trade periodical or a hunch based on the director or star or genre.

For historians, working in the archive involves serendipity and Pordenone intensifies this happy possibility. Films from the festival have found and continue to find their way into my research and teaching. Two years ago, the festival included a large number of silent social problem films, a key genre in my book project on women and silent cinema. Multiple reel fictional films, both realist and melodramatic, as well as single reel didactic "sponsored" films involving collaborations between reform organizations and film production companies were screened. One film, Manhattan Trade School for Girls (1911), about a philanthropic trade school, reiterates a strategy of individualizing the reform subject in case studies that I had been investigating in fictional films and reform texts. The case study was used by early twentieth century sociologists and reformers to delineate the particular circumstances of individual reform subjects. Its use in this didactic and quasi documentary one reel film suggests its broader social significance, one that goes well beyond the character centered formal feature of fiction films during the 1910s.

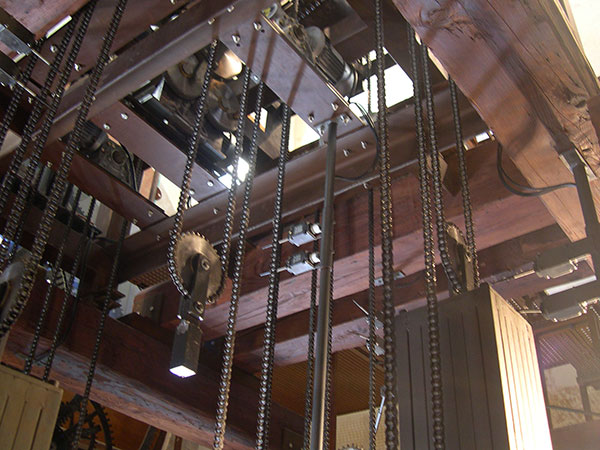

While silent films are not usually my students' first choice, I've developed a pedagogic strategy of topically pairing silent and contemporary films with the hope of making the earlier films more relevant and interesting. This strategy reinforces the inventiveness and formal sophistication of the earlier films but it also reinforces an important point about historical specificity. For example, this semester I am teaching a course on early and late cinematic experience as it relates to other cultural technologies from the 19th and 20th centuries (magic lantern slides shows and phantasmagorias, the railroad, photography, and the computer). I was stunned at Pordenone this year when I saw a scene in The Playhouse (Keaton, 1921) in which Buster Keaton plays all the musicians in the orchestra pit as well as all the spectators in the audience, a forerunner to a scene in Being John Malkovich (Jonze, 1999) when the actor John Malkovich, inside himself, plays all the characters in a restaurant. When I taught this course before, I used Malkovich to illustrate immersive strategies in digital media. This time I am pairing it with the Keaton film to foreground the difference between mechanical reproduction in photographically based cinema (drawing on the theorist, Walter Benjamin) and simulation, immersion, and digital effects in new "digital cinema" (drawing on Jean Baudrillard). Photographs I took in Venice of the Clock Tower, Torre dell'Orologio (1499), in St. Mark's Square for this course will illustrate another complex mechanical apparatus, one involved in shaping the experience of time.

Film Studies at Tulane is an interdisciplinary program with faculty drawn from various departments including Communication, French and Italian, Spanish and Portuguese, German, English, and Theater. We have developed an interesting curriculum that stresses the status of film as a specific medium and its importance as a cultural form in different national and historical contexts. I was able to attend Pordenone thanks to a Tulane Phase II grant. I hope one day we can send some of our students to film festivals including Pordenone to reinforce their understanding of cinema going as a cultural phenomenon and of the archive as a place in the present that makes the past visible.