To live in Russia is to come to a new understanding of space and time. The country devours time because of its space--and the roads that cover that space. With characteristic self-deprecation Russians will quote their nineteenth-century proverb: "The only thing Russia has in abundance is idiots and bad roads." Then there is the climate. Everything takes more time when the temperature is minus 10 or 20, when every step on paths rutted with black ice is an invitation to disaster. Or in brief but fierce summers in a country that has no defense against 90-degree temperatures, except to retreat to shade and leave serious work for another time.

Over the past three decades I have done research and photography in some very distant parts of Russia, such as the far north, and I have gained great respect for drivers of all ages who have negotiated that terrain for me. How do they do it? Apart from native skills, they have an important ally from an unexpected source: the Russian automobile industry. While the new Russians may have their Mercedes and Cherokees, for the true connoisseur of the Russian road, the ultimate machine is the UAZIK, Russia's equivalent to the classic Jeep. Four-wheeled drive, two gear sticks, two gas tanks (left and right), taut suspension, high clearance. Seat belts? Don't ask. The top speed is 100 km/h, but you rarely reach that if you drive it over the rutted tracks and potholed back roads for which it was designed.

No place in Russia has more of such roads than Arkhangelsk Province, a vast territory that extends from the White and Barents Seas in the north to its boundary with Vologda Province to the south. A combination of poverty, government default on both a local and national level, and distances that exceed those of most western European countries have created some of the worst roads in European Russia. And there is little hope for improvement in the foreseeable future.

Hence the UAZIK, whose name derives from the acronym for Ulyanovsk Auto Factory, located in the city of Ulyanovsk on the Volga River. Comfortable it is not, but an experienced driver can take this machine over rutted ice tracks in the middle of a snowstorm and not miss a beat. I should say at the outset that I am not such a driver, and I have only a vague idea as to how the contraption works. My job is to keep the cameras ready and scan the horizon for onion domes. But in my travels throughout Arkhangelsk Province, the UAZIK has performed superbly.

The fact is, roads were an afterthought in the Arkhangelsk territory. Settlers, hunters, and traders moved primarily over a network of rivers, lakes, and portages that defined the area as a geographically distinct cultural entity. Indeed, the settlement of this part of northern Russia, its gradual development, and eventual assimilation by Muscovy were based on a paradoxical set of circumstances--remoteness and wealth.

The wealth of its forests, rivers, lakes and the White Sea itself promised great rewards to those capable of mastering the area; and yet the remoteness of the area, the relative paucity of arable land (usually limited to certain river plains), and the length of the harsh winters discouraged extensive population growth. Those who succeeded in settling the area during the tenth through the thirteenth centuries proved to be sturdy, self-reliant farmers and craftsmen, a mixture of Slavs and Finnic tribes.

Moscow colonized the area during the next two centuries, and by the reign of Ivan the Terrible in the sixteenth century, the Dvina river system had become landlocked Russia's primary path both eastward to the Ural Mountains and westward to Europe. The importance of these routes faded after the founding of St. Petersburg in 1703, but the north again became a critical artery during the Second World War and the submarine race of the cold war between the Soviet Union and Nato.

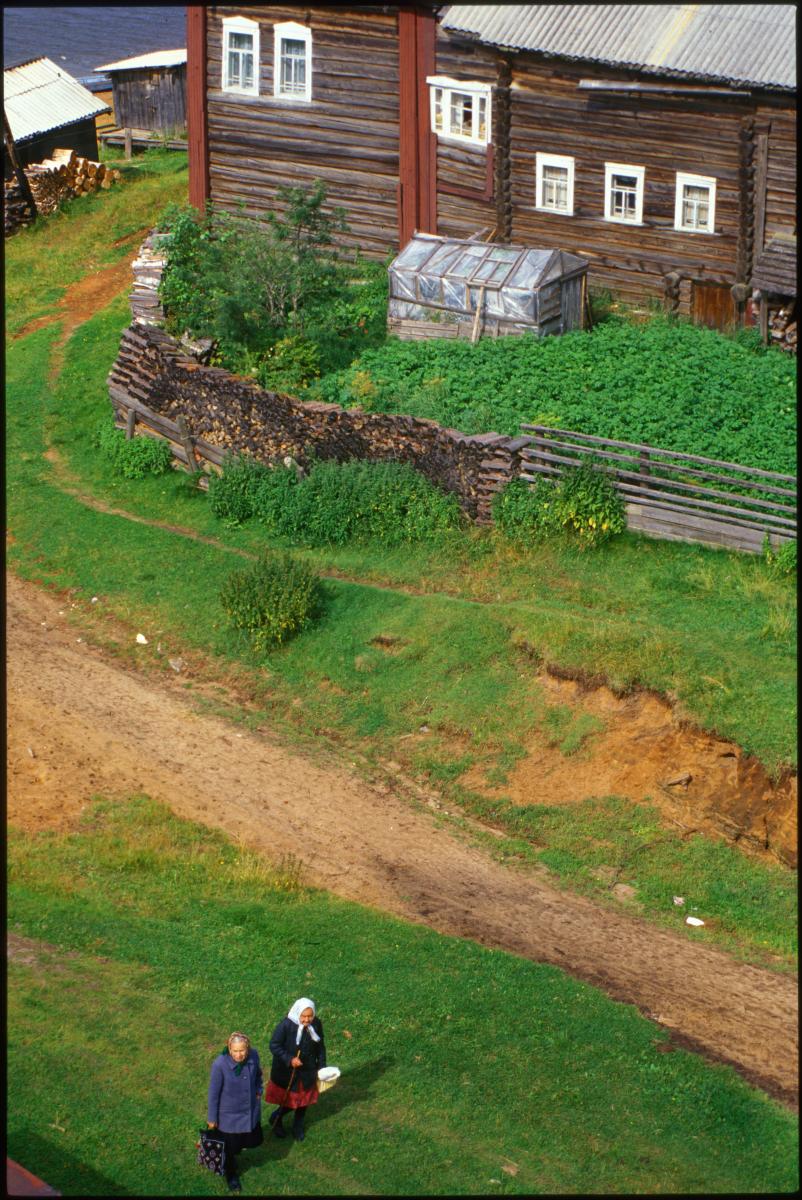

As a result, Western visitors were banned from the area until the late 1980s and have only been able to move with relative freedom there since 1991. My introduction to the Russian north began in 1988 with a trip to the fabled isle of Kizhi in the northwestern part of Lake Onega in Karelia. However, my prolonged study of that forbidden territory began only in 1995, when I first arrived in Vologda, capital of the province of the same name. Since that time I and my cameras have made several UAZIK-propelled forays to the Arkhangelsk, Vologda and Karelia regions in order to document the stunning, and perilously endangered, architecture treasures of the Russian north. The accompanying photographs give some indication of the beauty and the pathos of these remote areas.

Photographs by William Brumfield