One of the reasons I exhort my Tulane students to go to China is that by studying abroad in a city such as Beijing or Shanghai, they can witness historical change on a scale that is unimaginable in New Orleans. Yet for historians, China’s rapid transformation carries a high cost, not only in the destruction of classical architecture, but the elimination of the very documents we rely on to interpret and give meaning to the past. It is not uncommon for factories and other work units to simply trash their once treasured archives. As a result some historians have begun to work with paper recyclers in order to rescue valuable documents from the shredder. Given that many of these archives were recently off limits to Western scholars, the sudden devaluing of archival materials as “junk” thus represents a danger and a challenge.

Even libraries and academic centers are reconsidering their document collections. The Shanghai Academy of Social Sciences (SASS), a leading institution for the study of humanities and social sciences, recently decided to rid itself of their duplicate copies, no small matter given that this collection numbered nearly 100,000 volumes. Indicative of the perceived value of these materials within China, no organization stepped forward until the Institute of Sinology at the University of Erlangen-Nuremberg (FAU) offered to transport the collection to Bavaria. The result was the instant creation of a huge and open archive of materials, containing everything from Marxist classics to agricultural handbooks.

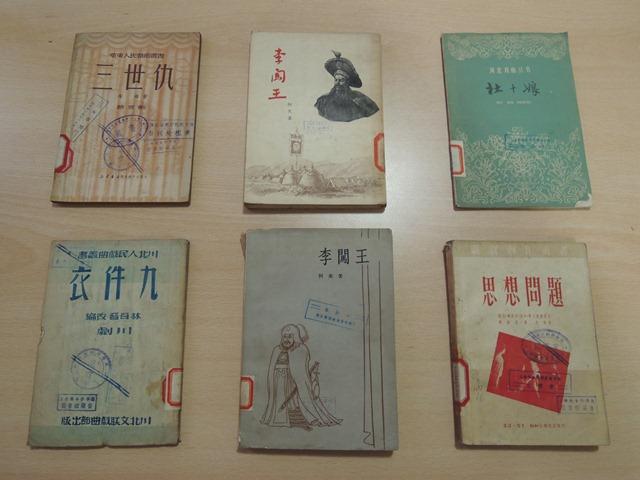

A few months ago I was invited by the Institute of Sinology’s Professor Marc Matten to visit FAU as part of their Guest Professor program in order to conduct research into my current project, which investigates the role of drama troupes during the Chinese revolution. As I was only able to stay in Erlangen for three weeks, I focused my research into two aspects of the massive SASS collection: drama scripts and literary journals. In both regards the collection proved a treasure trove of materials. In terms of scripts, I finally was able to track down a number of dramas that I had been long been reading about, but never able to decisively determine their content. For example, I had often come across references to The King Li Zicheng, a historical drama that was regularly staged during the Communist takeover of urban China during the late 1940s. Only by reading the work did it become clear that the intended audience for the show was not urban spectators but rural cadres, who were warned to maintain discipline as they arrived in cities.

Turning to literary journals, these documents, representing the official views of the PRC party-state, must be used with caution. Yet with careful reading, one can discover critical accounts of cultural work, providing rare insight into the problems of staging dramas at the village level. And even the typically glowing accounts of dramatic productions contain important details concerning cultural work, such as the mundane issue of selling tickets to shows in the countryside. These official journals, finally, are of great interest as they demonstrate how party artists attempted to match cultural policy to the rapidly shifting political terrain that marked the lead up to the Cultural Revolution.

While the research I conducted at the SASS collection was highly productive, introducing my research to a new audience through lectures and seminars was especially rewarding.

My talk at FAU, “Towards a Theory of Revolutionary Drama,” allowed me to work through some of the conceptual issues that I am developing in my current manuscript on the connection between dramatic performance and political action. I also led two seminars at FAU and was also able to present my research on early 1950s cultural work at the Free University of Berlin. Overall the experience of researching and teaching in Germany was a welcome reminder that the study of the Chinese past is an increasingly globalized affair.