During my recent sabbatical I spent my days largely at home, with books, pencils, paper, and a dog—a routine, it turns out, akin to that of my key subject, Emily Dickinson. I have been working on Dickinson’s poetry for over ten years, and despite her famous reclusiveness, my work has focused primarily on her incisive intellectual sparring with nineteenth-century ideas and institutions well beyond her four walls. Her poems played a key role in my first book, Miles of Stare: Transcendentalism and the Problem of Literary Vision in Nineteenth-Century America, and my next book is a study of Dickinson’s engagement with nineteenth-century American constructions of time. During my sabbatical I completed an essay on Dickinson that will become part of this book, and I wrote a chapter on Transcendentalism and women’s poetry, including Dickinson’s, to be included in The Cambridge History of Nineteenth-Century American Women’s Poetry.

My book-in-progress aims to build a new understanding of the ways Dickinson’s strange experimentations with time belong to a broader nineteenth-century American struggle to reconfigure time. Her temporal structures have often been read as pathological breaks from “normal” time or as exemplary instances of lyric temporality, but these approaches treat time as a universal or transhistorical concept and remove Dickinson from her historical moment. I begin instead with the assumption that time is a social construct—and one under especially intense negotiation during the mid-nineteenth century as notions of time and timekeeping were shifting rapidly and divisively in the wake of new forces such as the mass production of clocks and watches, astronomers’ selling of observatory time, the railroad (leading to uniform national time zones), the emergence of geological “deep time,” and the Civil War, which fundamentally challenged the nation’s temporal ideology of progress and destiny.

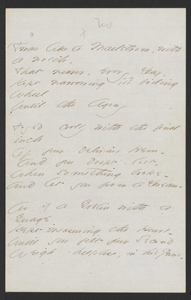

The first half of the book looks at the ways Dickinson uses poetic language to join her contemporaries in wrestling with these wider nineteenth-century ideas about time, while the second half, conversely, uses these historical ideas to reconsider the specific temporal questions about genre, publication, and historical transmission that have long preoccupied Dickinson scholars. We are all somewhat confounded by the nearly 1800 handwritten, unpublished manuscript poems she left behind upon her death: What is lost and what is gained if we put them into print? What form of posthumous publication do they require? Are they, as some have recently claimed, not meant for future readers (us) but for an intimate circle of historically specific individuals? Are we to read them only in their original form, in her handwriting? Are we not to read them at all? For Dickinson, what happens to poems upon the author’s death? What bearing should her sense of an author’s or poem’s temporal fate have on our own editing, printing, and reading practices?

These are the particular questions that occupied me during my sabbatical, and the article I wrote in response lays the groundwork for my larger goal of investigating how nineteenth-century temporal frameworks like teleological history and the measure of time increments affect the very temporal categories we use to understand (Dickinson’s) poetic genre, and how these historical frameworks were contributing to the ways Dickinson conceptualized what she wrote and what futures her writing might have. I made one trip during these months, which I suppose was also in step with Dickinson’s routines, as I went to her hometown, Amherst, Massachusetts, for the Emily Dickinson International Society Annual Meeting . There I gave a paper on Dickinson’s first posthumous readership in the 1890s, just after her death. I am looking forward to returning this August, when I’ll give a plenary talk at the 2015 Annual Meeting and visit the Dickinson collections at Amherst College and the Jones Library.