It was a late Sunday afternoon, and we had been driving for more than three hours between Manila and the rural province of Bataan. Our journey had taken us through the former U.S. naval base in Subic Bay and the rural municipality of Morong, and we had finally arrived at our destination, the former Philippine Refugee Processing Center (PRPC). Between 1980 and 1994, more than 400,000 Vietnamese, Cambodian, and Lao came through the PRPC, took English language and American culture classes, and waited for resettlement in the United States. It was considered to be a “model camp,” and unlike most refugee camps, all of the Indochinese waiting there had been cleared for resettlement. At its peak, it functioned like a medium-sized, yet international, city, with housing for thousands of Indochinese refugees, American and Filipino teachers, Filipino government personnel, and UNHCR representatives.

I was hot and tired, and ready for a shower and my bed; however, my tour guide and driver were more ambitious. The PRPC was no longer a refugee camp, and most of the facilities had either been torn down or were deserted. However, the administrators had built a museum documenting the camp’s history. My guides immediately went to the facilities director and asked him to open up the museum despite it being a Sunday evening. We had traveled a long way and wanted to take full advantage of our short time in Bataan. He let us in. Lining the walls were dozens of photographs and exhibits, highlighting the involvement of former First Lady Imelda Marcos, Pope John Paul II’s 1981 visit, and a mini-recreation of the “Monkey House” or the camp jail. There was also a trunk filled with dusty documents, old lesson plans, Cultural Orientation curriculum, newsletters, and photographs. I grabbed my digital camera and got to work.

Who is a refugee? What rights, if any, do refugees have? Which nation-states offer shelter and why? And how do refugee camps raise multiple questions related to sovereignty, citizenship, and international law? These questions seem particularly salient today, as we witness the more than four million Syrians fleeing civil war and relocating to refugee camps in Turkey, Jordan, and Lebanon, and now also making their way to Western Europe. However, in the 1970s and 1980s, the Western media was fixated on another refugee crisis: the boat people leaving Vietnam.

My larger book project investigates the history of Vietnamese refugee camps between 1975 and 1997, particularly in Guam, Malaysia, the Philippines and Hong Kong. This research trip was essential to my chapters on the Philippines and my interpretation of how the Marcos government used the language of humanitarianism in this late Cold War moment and how the refugee camps operated in the Philippine political economy.

I will use the materials I found on this trip in my analysis of the Philippine government, the UNHCR, its international staff, and the refugee communities. While in Manila I gave a talk at the University of Ateneo de Manila in a lecture series sponsored by Kritika Kultura, and I will present a related chapter on Malaysia at the Association for Asian Studies in Spring 2016. Along with my trip to Bataan, I also went to Palawan, and Manila, where I spoke to former Filipina English teachers, looked through old newspaper collections, and explored the remaining documents in Viet Ville in Palawan.

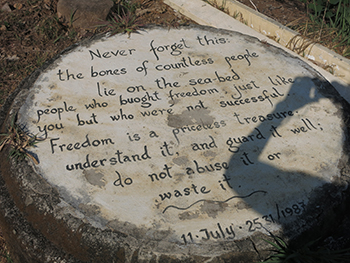

Before I left the PRPC, a current employee gave me a tour of the camp grounds. It was largely deserted and very few of the buildings remain standing. It was hard to imagine the same place populated by tens of thousands of refugees, sleeping quarters, classrooms, and outdoor markets. All of that is gone now. Instead, the preservation focuses on a series of former religious sites and memorials that the Vietnamese, Cambodian, and Lao communities created during the 1980s and the camp cemeteries. Separate from the photographs of community events and ESL lesson plans in the museum, these shrines indicate the ways in which the Vietnamese communities physically marked the camp and how Filipino nationals have sought to preserve and recognize these memorials even given their limited resources. Both the PRPC museum and the Indochinese religious sites underscore the inter-relationship between refugee stories and the Philippine social and political landscape.

Images below are from the former Philippine Refugee Processing Center, which is now the Bataan Technology Park, February 2015.

Photos provided by Jana Lipman.