Michael Brumbaugh, Assistant Professor,

Department of Classical Studies

In the wake of Alexander the Great’s death (323 BCE), his generals carved up the vast territory he had conquered and competed with one another to establish new kingdoms of their own. The most successful of these, King Ptolemy, came to rule over the rich territories of Egypt and Libya and established a dynasty that lasted nearly three centuries until it fell to the Romans during the reign of Kleopatra. Central to Ptolemy’s efforts was the use of what is today known as soft power (i.e., non-military coercion) not least because it promoted stability and was generally less costly than hard power.

In my research, I examine the role of intellectuals in Ptolemy’s capital city of Alexandria as influential actors in the manufacture and manipulation of this soft power. One in particular, a Greek from Libya named Kallimachos, came to prominence in connection with the king’s initiative to make his newly founded capital city the center of Greek and indeed world culture by establishing a great library and attracting intellectuals of every description to do research in it. Within this context, Kallimachos sought to exert influence over how the Greek kings of Egypt conceptualized their own power and represented it to the world. Unfortunately, our knowledge of this period – its personalities, politics, and institutions – is desperately fragmented. Despite having been revered by later authors as perhaps the greatest intellectual in antiquity, only one of the dozens of books Kallimachos wrote survives intact – a collection of six hymns. My book project, The New Politics of Olympos: Kingship in Kallimachos’ Hymns, restores that poetry book to an impassioned debate on the nature and exercise of power and what it meant to rule as king. Through it Kallimachos exerted influence in this contested political debate by bringing to bear a mastery of cultural knowledge that stretched back to Homer and the foundations of Greek literature and cut across disciplinary boundaries of poetry, philosophy, and oratory.

While Kallimachos’ own text can be found in most any library or bookstore, much of the evidence required to fill out the picture of his world is poorly documented, scattered across the globe, and far less accessible. During my recent research leave sponsored by Tulane and a fellowship from the Loeb Classical Library Foundation, I visited museum collections and archaeological sites in Switzerland, Greece, and Egypt to study objects recently discovered as well as ones languishing in obscurity. Further support from a Carol Lavin Bernick Faculty Grant, a Lurcy Grant, and the Department of Classical Studies over the last several years has enabled me to conduct research on this project at the Getty Museum in Los Angeles and the Fondation Hardt in Geneva, as well as to present my research to international audiences at conferences in Belgium and the Netherlands. Examining surviving material evidence first hand and discussing my work with specialists in different disciplines continues to be crucial to gaining a richer and more nuanced understanding of the ancient world in which Kallimachos operated.

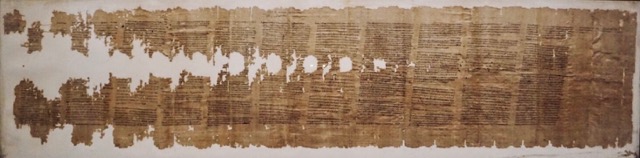

Papyrus Text of Kallimachos

Reading the Canopus Decree, one of four surviving Ptolemaic decrees written in Egyptian hieroglyphs, demotic, and Greek.