I was on leave during Fall 2009, following my third-year review. Mostly, I was here at home, with my wife and our sons, and in the library, trying to get some writing done. Meanwhile, the break from teaching gave me the chance to participate in some good adventures off campus, including workshops at the School of Advanced Research in Santa Fe, New Mexico (Figure 1), and at the Amerind Foundation, near Tucson, Arizona (Figure 2); the annual Southeastern Archaeological Conference in Mobile, Alabama; and the annual conference of the American Society for Ethnohistory, which was held here in New Orleans.

My interests include the archaeology of culture contact and colonialism, and, specifically, early contacts and colonial encounters between Native North Americans and European explorers and colonists. One topic I am studying is the architecture and built environment of Cherokee towns in the southern Appalachians (Figure 3), during the period just before and after European contact. At several sites, archaeologists have identified remnants of public structures known as townhouses (Figure 4), household dwellings (Figure 5), and large town plazas (Figure 6).

Meanwhile, burials are often placed within these architectural spaces, forming close relationships between the living and the dead. Our knowledge about these forms of archaeological evidence is enriched by documentary sources from the eighteenth century, recording trade talks and other events that took place in Cherokee towns and townhouses, and by Cherokee myths and legends. Some traditional Cherokee tales refer to mythological events that took place in townhouses, and they refer to mythical towns and townhouses present in the mountains and rivers of the southern Appalachians. This historical and mythological evidence can greatly enrich our knowledge of the archaeology of Cherokee settlements, and architectural adaptations by the Cherokee to new conditions of life in the southern Appalachians after European contact.

My other major current project—supported in part by the Exploring Joara Foundation—is an archaeological study of early encounters between Spanish expeditions and Native American towns in the upper Catawba River Valley in western North Carolina, along the eastern edge of the Appalachians. I am collaborating with David Moore (Warren Wilson College) and Rob Beck (University of Michigan) in this study of native and colonial groups at the northern edge of the Spanish colonial province of La Florida. Our current focus includes excavations at the Berry site (Figure 7), the location of the Native American town of Joara, where Captain Juan Pardo established the Spanish settlement of Fort San Juan in early 1567.

The town of Joara had been visited by the Hernando de Soto expedition in 1540, but Pardo built Fort San Juan as his primary outpost in the northern borderlands of La Florida. Pardo built five other forts, as part of an effort to establish an overland route connecting Santa Elena, the capital of La Florida, with the Spanish colonial province of New Spain—and, specifically, the Spanish silver mines at Zacatecas, Mexico, which had just recently begun producing vast amounts of wealth for the Spanish empire. The effort to connect Santa Elena with New Spain was abandoned after Fort San Juan and other Spanish outposts from the northern to the southern end of La Florida were sacked by Native American warriors in 1568—Santa Elena itself, located in coastal South Carolina, was burned to the ground in 1576 (Figure 8).

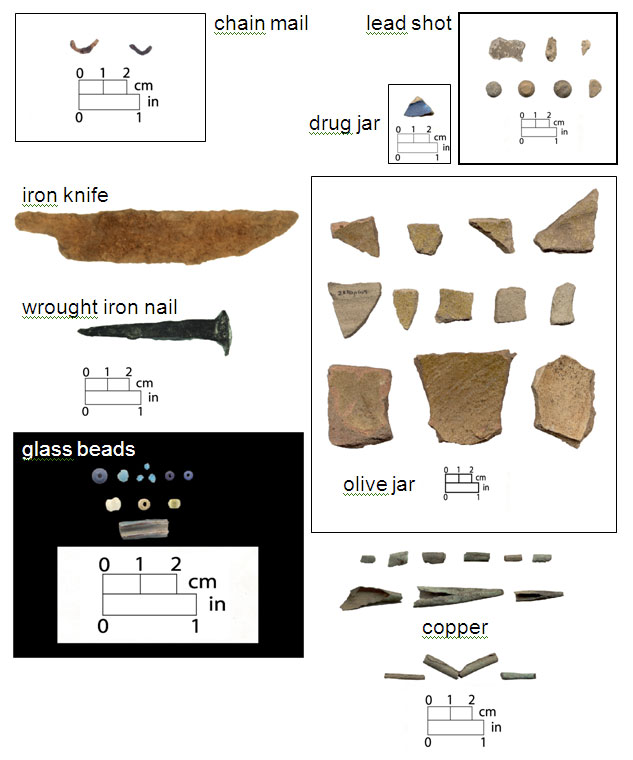

At Berry, we have found remnants of burned structures (Figure 9), as well as sixteenth-century Spanish material culture (Figure 10). Documentary sources make it clear that Pardo gave many talks to Native American community leaders, during which he gave them gifts, and during which he asked them to build houses for his men (Figure 11). We know these events took place at Joara, and we interpret the structures we have found at Berry as houses built by the people of Joara for the Pardo expeditions. Relations between Pardo and the people of Joara began favorably—interactions between these groups are a major focus of our current research, as are the outcomes of the abandonment of Fort San Juan.

Pardo’s outposts were vulnerable, and the fortunes of Pardo’s expeditions were tied to broader developments in distant places within the Spanish colonial empire in the New World. Furthermore, even though Fort San Juan was located at the very edge of the Spanish colonial world—supply problems probably contributed greatly to its vulnerability and its failure—the history of Fort San Juan had significant implications for the broader course of European colonial history in North America. Attacks on Spanish outposts throughout La Florida—from mountains to the sea, from western North Carolina down to the Florida Keys—led to major changes in Spanish colonial activity in North America, and created openings for French and English exploration and settlement in the 1600s and 1700s.

I will be back in the field in North Carolina in June 2010, and one of my graduate students will also be doing excavations for her dissertation research in July and early August. Please come visit—our field house is located in a town at the edge of the mountains, halfway between Asheville and Charlotte, and we will be hosting our annual open house at the Berry site on June 26 (Figure 12).