Most of my work as an academic consists of sitting alone in a room reading and writing about men and women who sat alone in rooms reading and writing. It does not exactly lead itself to exciting narrative, but it is not without its moments of drama. I am currently writing a book about mystic language in Spain between 1500-1700. My fourth year leave enabled me to travel to archives in Madrid to examine a genre that flourished during those years and has almost never been seen or heard from since: the spiritual autobiography. These are narrative accounts of divine visions and other mystic experiences. Saint Teresa’s Libro de la vida is well-known, but what is less studied is the furor for spiritual autobiography that she set off. Every nun who could sign her name seems to have written at least a few folios about her visions. Almost none of these accounts have been published—the weirder, less coherent, and less “literary” the account, the less likely it was ever edited or published—and many of them can only be accessed in the original.

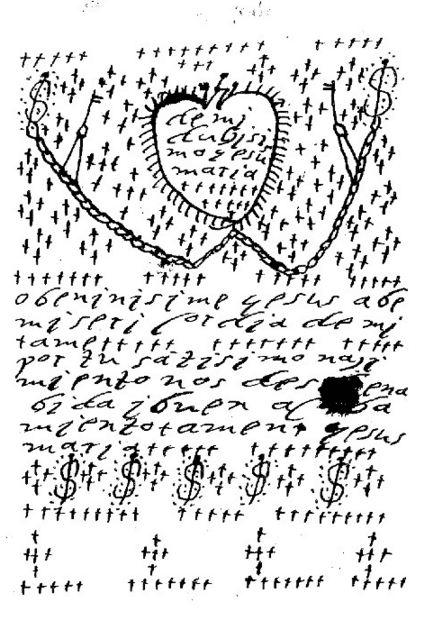

These are not easy texts. Many of the nuns wrote copiously, repetitively, and often incoherently (my favorite discovery from this trip were the 23 notebooks of a nun who wrote in all directions and seemingly on any available scrap of blank paper, often on top of previous writings). The “mad scribblings” are precisely what I am interested in; my argument is that that the selection of Teresa’s polished, well-organized autobiography as representative of this genre has given scholars a mistaken idea of the way that early nuns wrote about themselves. Even for those texts that have been edited and published, seeing the originals is essential, as the process of editing often removes dissonant elements, making the text conform to a modern notion of what “makes sense.” For example, the narrative of Luisa de la Ascensión certainly reads differently in a modern prose edition versus seeing a drawing like this [image] on one of the folios.

But sitting for hours in a distinctly, and, one suspects, intentionally uncomfortable chair, reading page after page of at times illegible seventeenth century handwriting, can be enough to make one start having hallucinations oneself. And even the chairs are not enough to keep one from nodding off now and again, so I made frequent trips to the fabulous 40 cent espresso vending machine. If I had to import one element of Spanish culture to the United States, it would be the espresso vending machine. There is a lovely camaraderie formed around the espresso machine as tired but stimulated researchers clutch little cups and sip their liquid energy. Perhaps someone from the business school would like to work with me on this...