Literary scholars are often compared to detectives. Much like Agatha Christie’s Miss Marple or Stieg Larsson’s Mikael Blomkvist try to decipher enigmatic clues to solve mysteries, researchers in literature grapple with ambiguous texts, examining their narrative structure and figurative language closely for clues that will help unveil their hidden meaning. Scholars who work on the literature of older periods often attempt to crack the mysteries of literary texts not only through careful analysis, but also by hunting for clues about those same texts in historical archives. That is exactly what I had the fortune to do during my 2015-2016 research leave. Thanks to the generous support of the School of Liberal Arts, the Lurcy Foundation and the Louisiana Board of Regents’ ATLAS program, I was able to spend the first months of my leave huddled under the green lamps of the silent reading rooms of Parisian archives, tracking down rare documents from the seventeenth century that would shed light on the ambiguities in the plays I discuss in my book manuscript in progress, All the World’s a Stage: Performing Globalization in Early Modern France.

In this book I explore the ways in which French seventeenth-century playwrights represented the growing interaction of different parts of the world during the early modern era. As I struggled to decipher these authors’ supremely ambiguous plays for the different chapters of my book, I realized that I had to delve deep into the dramas’ historical context; it was there that I might find the keys to unlocking their difficulties. This realization pointed me in the direction of the National Archives in Paris, fittingly located in the historical Marais neighborhood which is as much a product of the 1600s as are the plays I discuss in my book.

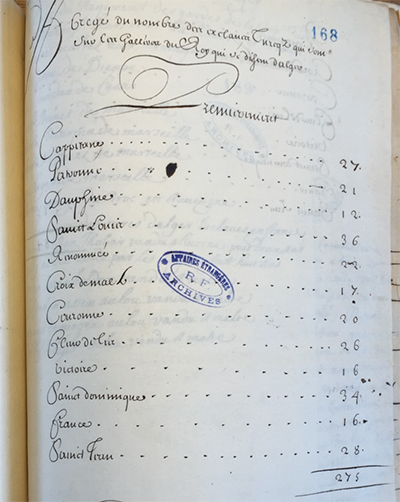

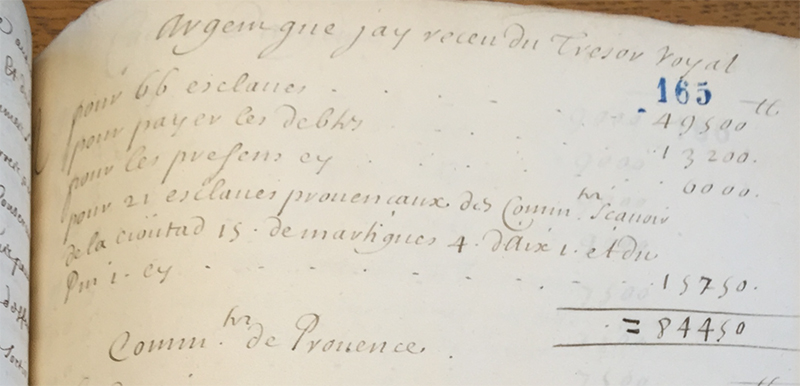

At the National Archives I searched for clues about French attitudes towards slavery in the seventeenth century, attitudes that would help me better understand the representation of servitude in plays like the anonymous tragedy of The Cruel Moor and Molière’s comedy-ballet The Sicilian. While dissecting these plays either criticizing Spanish slaveholding or celebrating the French use of slaves, I had been haunted repeatedly by a particular question: How could the French reconcile their own enslavement of North Africans and sub-Saharan Africans with their own long-standing domestic ban on slavery? My search led me to a number of documents, including a supremely fraught attempt by the French Minister of the Navy to justify the nominally illegal presence of North African slave rowers in Marseille and aboard navy ships by observing that the navy had bought them at slave markets abroad where such practices were illegal. Still other documents I found blithely discussed the use of sub-Saharan African slaves in Mediterranean ports and on navy vessels.

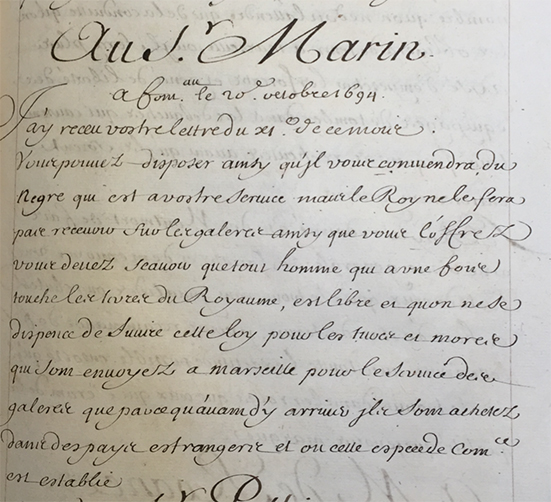

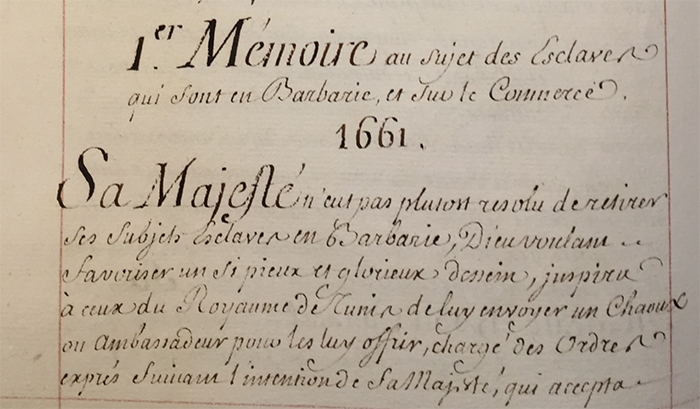

I also looked for clues at the archives about the representation of another form of cross-cultural contact, the conversion of Christians to Islam, which is a major theme of two plays in my book, Mainfray’s tragedy The Rhodian Princess and another comedy-ballet by Molière, The Bourgeois Gentleman. Both plays feature characters that clearly serve, or aspire to serve, the Turkish Ottoman Empire, yet never unequivocally convert to Islam, unlike characters who clearly do so in the contemporary English plays A Christian Turn’d Turk and The Renegado. To try to understand the reasons behind the French playwrights’ hesitation to portray the conversion to Islam unequivocally, I had to understand better French attitudes towards this phenomenon. Thus I scoured the French consular correspondence for descriptions of Christians who had converted to Islam while enslaved in North Africa. I found a number of remarkable documents, including a French consul´s scathing account of the supposed proclivity of the inhabitants of Provence to change religion and a fascinating narrative of a diplomatic mission to ransom French slaves in North Africa. These fascinating glimpses into the multicultural world of the early modern Mediterranean deepened my understanding of Mainfray and Molière’s plays.

After sleuthing around in the Parisian archives, I spent the rest of my research leave in sparsely-populated Iceland working on my manuscript at an almost empty National Library in Reykjavík. I am grateful to the School of Liberal Arts, the Lurcy Foundation and the Louisiana Board of Regents’ ATLAS program for supporting my archival work and writing in 2015-2016.