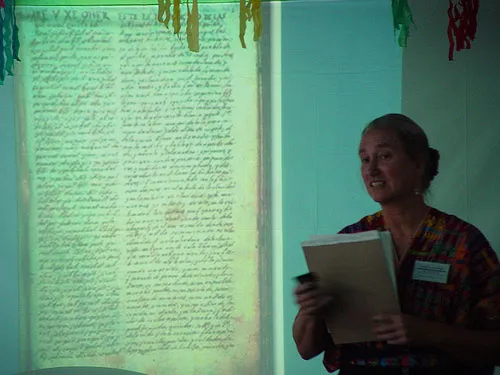

This weekend I attended a conference on "development" in Guatemala. The conference was sponsored by Wuqu' Kawoq, an NGO dedicated to providing health services in indigenous communities. The doctors, nurses, and health promoters not only speak the Kaqchikel, the language of their patients, but they will even make house calls. They also do research, amassing statistics on morbidity and moribundity, but also on traditional herbal medicines and their efficacy. They have published a book (Peter Rohloff and Magda Sotz Mux (2008) Tiqaq'omaj qi': Plantas medicinales y enfermedades comunes. Wuqu' Kawoq: Bethel, VT. title translated: Let's medícate ourselves: Medicinal plants and common illnesses.) on these natural medicines, which they distribute freely to clients and health workers. Their work in indigenous Guatemalan communities brings members of Wuqu' Kawoq into close contact with other NGOs. The proliferation of such organizations in recent years is astounding. Some estimates place over 1,500 such organizations in Guatemala, hence, a conference to provide a forum for exchange among the different players and stakeholders. This conference, however, was not your "average bear" conference. It was not held in Guatemala City. It was not at an international chain hotel, no Ramada Inn, Westin, Hyatt, or Hilton. Rather the conference was held in Santiago Sacatepéquez (Pa K'im in Kaqchikel). The papers were given in the covered patio of the home of Wicha, one of the Wuqu' Kawoq health promoters. The PowerPoint led projector and associated laptop were powered off a battery; the images projected onto a sheet tacked to the plaster wall. Pine needles strewn over the patio floor kept the air fresh and crisp, even during heated discussions. As Santiago only has running water a few hours a day, huge basins held reserves in front of the restroom, so that attendees could bucket flush after using the facilities. A cadre of women worked during the morning session to prepare lunch, which was served to all comers at the noon break. We had great food: the first day, Friday, we were served pul ik (recipe); Saturday we had xaj q'utu'n (recipe); Sunday we enjoyed crispy fried chicken, rice, and "Russian salad". Each day the hot sauce, served separately, was picante, sharp and spicy.

But what really set the event apart was the range of experience and ethnicities of the participants. There were health promoters from remote villages whose Spanish was halting, though delivered with passion; there were national representatives of international agencies, such as the Inter-American Foundation, who were polished, urbane, and committed; there were local representatives of grassroots organizations, seasoned in the political fight for recognition and support; there were international development officers representing their organizations' efforts to bring services to remote communities (e.g. Planned Parenthood, Namaste' International (a micro-finance NGO)); and there were international scholars, Fulbrighters, researchers, teachers, me. Plenty of time was programmed for discussion after presentations and the interchanges were always lively; no one pulled any punches, but the only ones to withdraw from the conference activities were a group of "city" lawyers, who found the accommodations in Santiago inadequate. I found the whole event stimulating; I met people from groups, organizations, and communities with whom I ordinarily have little contact. There is a website for the conference. Eventually, the powerpoints should go up on the site; photos are up now. I won't recap the papers and can't begin to capture the discussions. Dr. Zambrano took notes, which also should be posted: www.futuroscolectivos.com

Just a few vignettes:

Vignette One:

Jun ti natab'äl. I have only been a few homes in Santiago, so I was a bit surprised when the shuttle from Antigua pulled up in front of a place I'd been years ago, visiting for the patron saint's day, July 25, Día de Santiago. At that time, the cofradía, confraternity dedicated to Saint James, was headquartered in this house. I had three students with me from the Kaqchikel class, two first-year students, and one-third year. We were invited in. Stepping into the covered patio after the glare of the street was like stepping into a cave. Cooking fires dotted the patio floor and stretched into a back room; groups of women were clustered around the fires, some patting out tortillas, others stirring pots. The floor between the fires was strewn the pine needles. We were ushered into a long narrow room at one end of the patio. Here the patron saint and his entourage of less central saints presided over an altar at one end of the room. Four elder women knelt on pine at the foot of the saints and kept up a melodious murmur of prayer. The male members of the cofradía were seated, in order of rank, on benches that lined the other three walls of the room. A spot was cleared for us at the low-end of the bench order. We had arrived in the midst of pixa' "counsel"; members of the cofradía were giving short speeches, exhortations outlining proper conduct, prescribed and proscribed actions, problems to be confronted, and plans to do so.

When the speaking baton got around to us, it was clear that we were meant to participate. Luckily my third-year student loved to speak publicly in Kaqchikel; he got up and gave a perfectly molded pixa'. As one of the first-year students and I were the only women in the room not kneeling and praying to the saints, I was not sure that we would be expected to speak. But the baton passed to me. I got up and gave what I hoped was a properly motivational speech. I spoke long enough to get the two first years off the hook. Then the leader of the cofradía took the baton and the floor and used our presence and our speeches as a launching pad for an exhortation to conserve Kaqchikel language and culture; the argument ran that if these gringos come from so far away to learn this, it must have value, and more value than Spanish, which is more generic and less uniquely Guatemalan or Santiagueño.

So anyway, when I found we had come back to this house, I entered with some wonder. Coming into the covered patio was still like entering a cave. I walked past the registration desks to the door to the erstwhile saints' room. There was still a small altar at one end of the room, but Saint James had moved on. I found Wicha, our hostess, and asked about the cofradía. I learned that her father had been the leader and had hosted the saint often in its rotation, but that her father had died and no one in the family was now in the confraternity.

Vignette Two: Ruka'n ti natab'äl

On the last day of the conference, no papers were given. Time was provided for a final discussion. Seated in a circle, we shared our perceptions of the "take-home" values of the conference, as well as projections for further work and collaborations. Then we walked up one of the many hills of Santiago to the Wuqu' Kawoq house/clinic. There, in the patio, we held a Mayan ceremony to give thanks for the success of the meeting and to bless the participants and their respective institutions. When I saw the patio area, I was a little dismayed at it was in full sun and I had come with no headcloth and no sunblock. I must have muttered something about this under my breath, as the daykeeper, Rolando, who was to lead the ceremony, offered me his spare headcloth and asked me to act as his gofer. Since how one wears the headcloth indicates rank and as I wasn't sure what rank he was ascribing me, I elected to fold my sweater into a sort of head covering, which didn't work worth a fig. Every time I had to sort out another set of candles for individual offerings, it would slip off, so the sweater spent most of its time on the pine needle floor-coverings.

The ceremony got off to a little shaky start. Rather than light the central fire, with its offerings of incense, candles in nine symbolic colors (counting "lard" as a color), two kinds of block chocolate, and pastries, Rolando had each participant hold 13 assorted candles, light them, pray over them, and then place the candles on the pyre. As luck and wind would have it, the clutched bunches of candles flamed up for many participants. Rolando hadn't finished his instructions when some people began to be scalded by the dripping wax. Seeing this, he urged them to quickly lay their candles on the central offering, but several handfuls of candles hit the patio and pine before their bearers could reach the altar. Luckily no pine caught fire and all the candles were recovered and consigned to the principal fire. Those who had dropped their candles were discomfited; but Rolando glossed over it, saying not to worry, that this occurrence, as all during a ceremony, had a meaning, but that he would explain later. He did explain, after the ceremony, that the burning and dropping was an indication of one's interior state. Those who came to the celebration with doubts or reluctance would be unable to hold the candles long, as they wouldn't be able to concentrate energy to transmit spiritual messages to the candles and through them to the invoked spirits. Of course, he explained this in Kaqchikel. I'd been translating periodically, but I did not translate this explanation. By this point everyone was pretty wilted from three and half hours in full sun, I don't think they were tracking what anyone said.

Once the fire was lighted by the first set of candles, dropped or not, the flames were lively and many messages were transmitted. By happenstance, it turned out that we had 20 people who were willing to participate fully in the ritual. There was a second tier of "participants" who disposed to make some offerings but would not join the full circle. There was a third tier of those who hung out in doorways and under eaves and watched but refused to hold candles, join hands, or walk around the fire. But having 20 in the inner circle was serendipitous. There are 20 named days in the cholq'ij (ritual calendar - The cholq'ij, called tzolk'in in Yucatec Maya and by therefore by most epigraphers, is a 260-day cycle, composed of 20 named days with 13 numeral coefficients (20 x 13 = 260).). Rolando appointed each person in the circle as the avatar of a day; we were each to offer 13 candles and a handful of cuilco (coin-shaped incense lozenges) as our respective day was invoked and addressed. In addition, we each held 4 candles which were to be offered on the day of our own nawal, spirit guide associated with our birth date. This caused an immediate snag, as many people didn't know their nawals. Ironically, all the gringos present knew theirs. The woman from Peru did not, nor did many of the Maya, including several working for Wuqu' Kawoq. Rolando told them just to place their quartet of personal candles in the fire on the day Toj, the day associated with lightning and payment of debt, monetary and spiritual. Things went fairly well through the first seven days. But after Ey "Tooth", for some reason, five people just suddenly came forward and all offered their candles and incense and then stepped out of the circle. This meant we had to re-distribute candles to the first avatars to be able to finish the count. The fire received all the offerings thankfully and returned positive messages, though with the injunction that Dr. Rohloff would have to give greatly of himself to ensure success of his organization and the clinics he has set up.

One of the indications of a successful ceremony is that the fire burns brightly and long, allowing much communication. Since those performing the ceremony have initiated the dialogue with God, with the ancestors, with the spirits and positive energies, it behooves the celebrants to speak as long as the channel of communication is open, which means you cannot walk away from a lit fire. As long as the fire is burning, you need to be in prayer. Long before the fire died out, the celebrants, even those of the "inner circle" had retreated to the patio edges, seeking shade next to the walls, under eaves, even in the outhouse. As assistant, I had to stay accessible/sun-burnable. As the fire began to die down, Rolando invited two women from a local Evangelical Church to come forward and sing. These women, who had been in the third "circle", came forward and sang two hymns in close harmony. Then the ceremony closed out, all participants, from all the circles, hugged each other; then we all headed back down the hill to Wicha's for lunch. Sharing food after a ceremony is an important part of the celebration of community.

Final vignette: Ri k'isib'äl natab'äl

After lunch, two young men and their mentor, from a Santiago kite-making team, came to give us a talk on the tradition of making and flying kites for November 1 and 2, All Saints' and All Souls'. Many Maya communities share the belief that one may communicate with the spirits of the departed on these two days through kite-flying in the graveyards. In Santiago, kite-making has evolved as an art form. There are many youth associations who band together for the months preceding All Saints' and All Souls' to make giant kites. Some of the kites are 4 meters in diameter. There are competitions for best kites in several classes, including voladores (large kites that can still get airborne with the skill and strength of 10-14 boys) and de exhibición (giant kites that will never grace the sky). The young men who visited us brought a 2.5 meter kite with them, which they put together before our eyes, complete with cloth clotted twine tail. One young man, Germán, gave most of the talk, with occasional additions by the mentor. Germán impressed me with his poise, his showmanship, his fluency in Kaqchikel, in Spanish, and English, and his knowledge of the symbolic and cultural significance of the kites, their construction, their flying and their final conflagration at the cemetery. After the talk, I asked him what grade he was in. I guessed he was about 15. He told me he had finished "básico" (grades 7-9 of a 12 grade system), but that he was no longer in school, though he had wished to continue; his father had pulled him out to work in their fields of corn and broccoli. I hope to find out from Peter (Dr. Rohloff) what the deal is here. If his father really needs the labor,….. If it is the financial drain of the next three grades, …… There is an Instituto in Santiago that goes through 12th grade; it is supposedly free, but there are fees for materials needed for class projects, for activities, and for required events. My comadre, who is principal of a grade school in an aldea, "village", of Santiago, estimated that the expenses might come to Q300 a month (about $45). Ah well….

Final vignette: Ri k'isib'äl natab'äl

In a final irony, when I got back to Antigua, a friend who works for the World Bank said he HAD to speak with me. It turns out that World Bank is helping to finance the Guatemalan First Lady's Mi Familia Progresa "My Family Progresses" Project. This initiative gives mothers Q300 every fortnight so that they will keep their children in school and will get them the necessary vaccinations. My friend wanted me to undertake a quick ethnographic survey of sample recipients to document actual uses of the funds, hopefully to disprove circulating rumors of misuse or misdistribution of these monies.

Santiago is not one of the communities included in this project; and Germán is older than the grade school children targeted as beneficiaries.