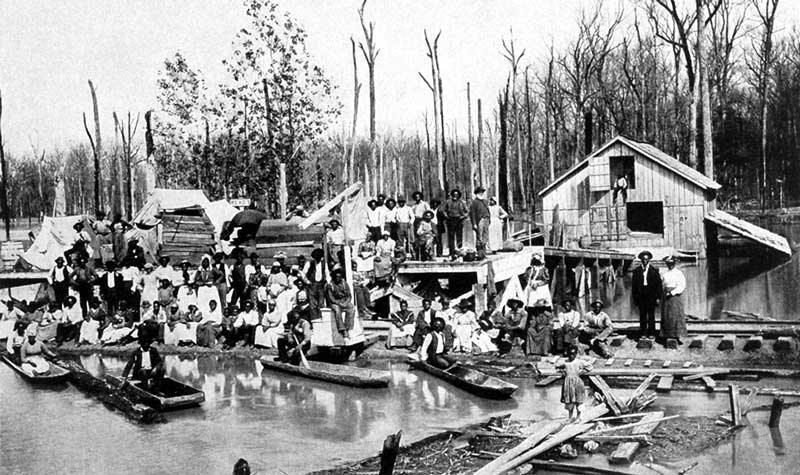

One of the most destructive floods in the history of the Mississippi Valley occurred in the spring of 1912. Owing to the heavy and late snowfalls and the somewhat sudden melting of the snow in the latter part of March and the first part of April, a vast volume of water poured into the Mississippi River from its tributaries. Water from the river either overflowed or broke the levees, leaving hundreds dead and thousands displaced.

As the Mississippi River rose in Greenville, Mississippi, in April 1912, an engineer had what The New York Times reported the next day was a “brilliant idea.” The river threatened to wash over the levee and flood the city. So, the young white man ordered several hundred African Americans to lie down on top of the levee, one on top of the other. They stayed there for an hour and a half, “uncomplainingly,” the Times asserted, a “human wall” holding back the mighty river until their bodies were replaced with bags of sand.

It had happened before. During a flood in Baton Rouge in 1852, three thousand enslaved people had been compelled to hold back the water. That time, wielding “pickets from rail fences,” they were made to keep the river in place for a full 24 hours.

Floods sometimes appear to belong to the realm of nature, beyond human history, the cycles of rain and the force of gravity combining in the seemingly timeless and inexorable flow of water into the sea. But historians know that acts of god, as many call them, are bound up in the acts of women and men. We no longer force people to form what the Times called “human dikes.” Nonetheless, as I watched the Mississippi River rise this summer, I knew that floods tend to disproportionately harm people who are already disadvantaged. I knew that the Army Corps would be faced with difficult decisions about which spillways to open, and thus whom to flood. I knew, too, that the 20th century’s solutions to the problem of flood control probably won’t survive the 21st. I couldn’t help but consider, therefore, how our infrastructure today continues to rely on structural inequalities, and to wonder how our own “brilliant ideas” for flood control will hold up in the future.

Horowitz’s book Katrina: A History, 1915–2015 is forthcoming from Harvard University Press in 2020.