As the U.S. approaches Election Day on Tuesday, November 3, 2020, Americans face a campaign unlike any they have seen in recent memory. Not in a century have Americans been asked to vote amid a global health pandemic, and the unique context of the 2020 campaign means voters will have a lot to consider as they prepare to cast ballots.

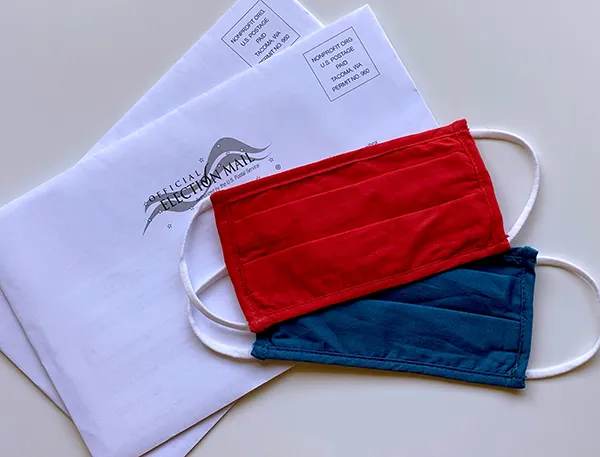

Of course Americans will not cast ballots only on November 3rd—many states have implemented forms of convenience voting that expand the period in which voters make up their minds and select their preferred candidates. Convenience voting takes many forms: in-person early voting, no-excuse absentee balloting, and all-mail elections. All told, 42 states and the District of Columbia offer voters a means of casting a ballot before Election Day.

There is significant scholarly interest in the impact of convenience voting on individual voting behavior and aggregate election outcomes. My own research suggests that the implementation of early and convenience voting systems does not, by itself, increase turnout, though convenience voting coupled with candidate and party mobilization can increase turnout. This position echoes a study by J. Eric Oliver suggesting voters are two percent more likely to vote when the availability of convenience voting is coupled with mobilization efforts. All-mail elections can also produce an increase in voter turnout, though the effect varies by type of election.

A great many states have adjusted their voting methods to account for the COVID-19 pandemic. These temporary changes are often justified as helping to reduce in-person voting and the subsequent possibility of virus transmission as voters wait in line. But these changes are not without controversy; critics argue that expanded absentee/mail balloting will not only challenge the ability of elections officials to count votes in a timely manner but also increase opportunities for election fraud. However, the evidence that absentee/mail ballots are characterized by fraud is astonishingly small. Using data collected by The Heritage Foundation, researchers found only 44 cases of voter fraud in recent elections out of nearly 50 million ballots cast.

Regardless of when and how Americans vote, one thing is nearly certain: once the polls close on November 3rd, we will still be in for a very long evening. Recent presidential elections have not been called until 2:30 a.m. Wednesday (2016), 2:00 p.m. Wednesday (2004), and 36 days later (2000). With high levels of interest in the 2020 election and a likely surge in absentee/mail ballots that will have to be counted alongside Election Day votes, Americans may go to sleep on November 3rd without yet knowing who will be president come January 20, 2021.

Brian Brox is an associate professor in the department of political science and the director of the U.S. Public Policy Summer Minor. His research and teaching focus on the American Government, Political Parties, Campaigns and Elections, and Political Behavior.