When I completed research for my first book, Women against Abortion: Inside the Largest Moral Reform Movement of the Twentieth Century (Illinois, 2017), I observed that nurses had formed many of the first grassroots anti-abortion groups in the United States. This puzzled me because physicians, pained by treating so many women who had suffered botched abortions, had been among the most vocal proponents of decriminalization. Members of other female-dominated professions, including social work, generally supported decriminalization, too. I began investigating the dynamics of American nursing in the 1960s and 1970s in order to understand why nurses understood abortion differently.

My investigation of nursing between 1967 and 1973 revealed a profession in turmoil. The enactment of Medicare and Medicaid, coupled with new medical technologies and more jobs that offered health insurance benefits, prompted millions of Americans to seek professional medical care instead of self-treating at home. While demand for professional medical care soared, nurses’ salaries remained stagnant. Despite the low pay, long hours, and physical demands of the job, young working-class women entered the profession in order to join the ranks of the middle class. Concurrently, the civil rights and feminist movements empowered Americans demand reforms in medicine—from laws that prohibited physicians from prescribing birth control to quotas that limited the numbers of women, racial minorities, and Jews in medical schools.

In a forthcoming article in the Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences, I explore the tensions between the first generation of women who sought legal abortions and the nurses who cared for them. While most abortion opponents framed their objections in religious terms, nurses generally opposed abortion for secular reasons. Some had initially supported decriminalization, but changed their minds when women’s demand for the procedure burdened already understaffed obstetrics units. Many more complained that they were not trained to care for abortion patients. As a consequence, nurses often formed opinions about women who sought abortions without much context. In comparison, social workers, who often had long-term relationships with women and their families, were much more likely to sympathize with women who did not wish to continue with their pregnancies.

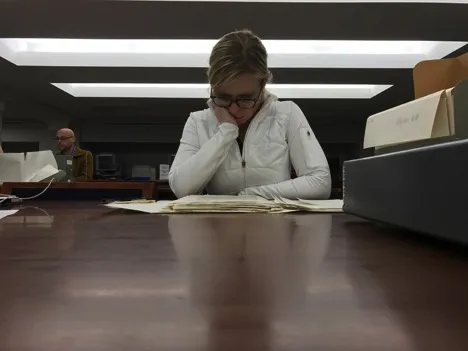

The article on nurses’ work with abortion patients will be included in my next book, Nursing Revolution: Civil Rights, Feminism, and the American Nursing Profession. An Awards to Louisiana Artists and Scholars (ATLAS) grant and the COR research fellowship permitted me to conduct additional archival research in Philadelphia, Chicago, Houston, Iowa City, Denver, and Washington, DC. I am completing a chapter about race discrimination in professional nursing programs in the 1960s and 1970s. Although African American comprised over eleven percent of the US population in 1965, only three percent of nursing school graduates were students of color. My preliminary research suggests that hospital-based diploma nursing school administrators immediately flouted the employment and educational reforms demanded by the 1964 Civil Rights Act; many of their strategies would later animate the backlash to affirmative action in the 1980s. I will write additional chapters about nurses’ work with HIV-positive patients in the 1980s and nurses’ work to combat sexual harassment. Two undergraduates with internships from CELT and NCI are helping me to organize my research. When I return to the classroom next fall, I will look forward to drawing upon this new research to animate my lectures in courses on the history of medicine, women, and reproductive health.