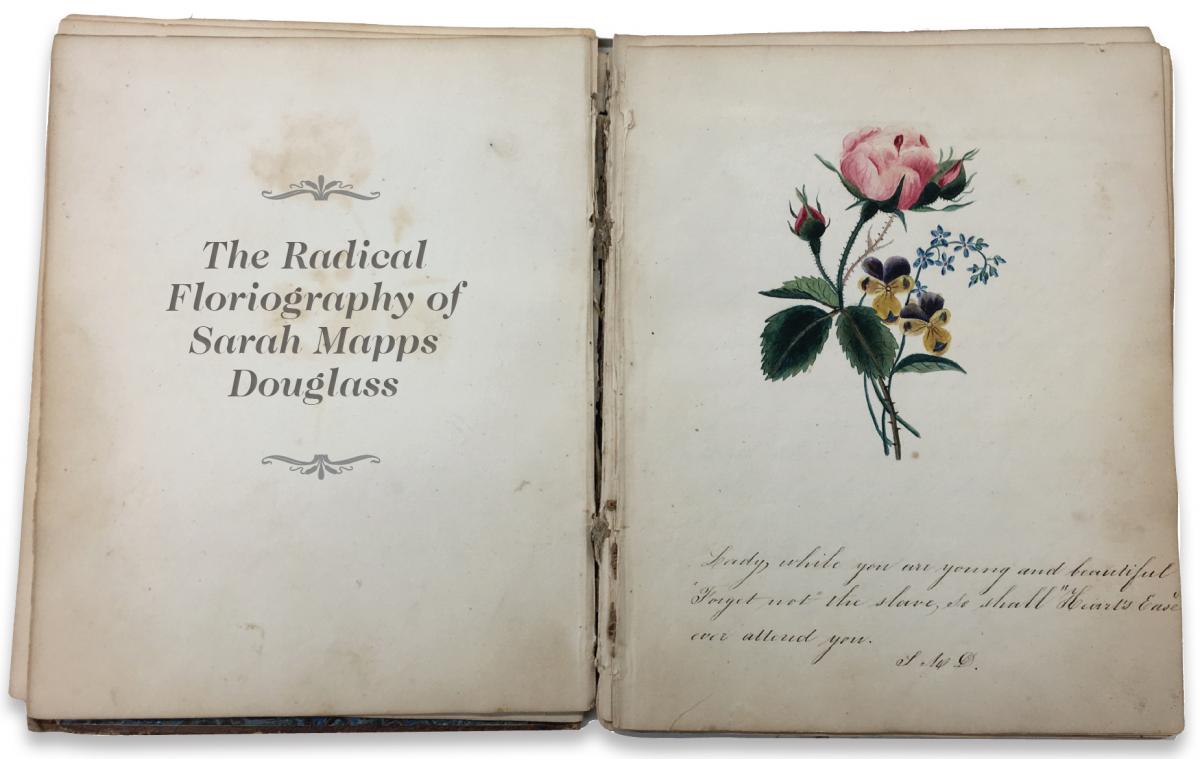

Sometime in 1836 or 1837, Sarah Mapps Douglass, a thirty-year-old schoolteacher and prominent member of Philadelphia’s free Black elite, painted a lovely watercolor of a floral bouquet in the friendship album of Elizabeth Smith, the teenaged daughter of committed white abolitionists Gerrit and Ann Smith. A large pink rose blossom and diminutive rosebud dominate the charming composition, while more humble flowers—a dainty sprig of blue forget-me-nots and two specimens of the purple, yellow, and white wild pansy known as heart’s ease—accent the larger stem. This seemingly innocuous little painting might initially strike the viewer as little more than a conventional display of feminine accomplishment de rigueur of the period, just the sort of trifle that one refined lady might offer another as a token of friendship. However, beneath the image Douglass penned a powerful inscription whose sharp puns dramatically transformed the significance of her flower picture: “Lady, while you are young and beautiful ‘Forget not’ the slave, so shall ‘Heart’s Ease’ ever attend you.”

Somewhat of a fad among fashionable young women of the period, friendship albums were bound volumes kept by individuals that contained blank leaves upon which the owner’s invited friends would offer gifts of writing or, occasionally, drawings or small paintings. Existing at the nexus of public and private, the albums might be displayed in a parlor and even loaned out over the course of a few days in order to be inscribed. Therefore, while the offerings made therein were personally addressed to the book’s owner, they were also meant for the consumption of a select public.

In contrast to Douglass’s pointedly political offering, most album contributions celebrated the bonds between writer and recipient with sentimental paeans to friendship or offered some other gender-appropriate message conveyed in the polite language of refined femininity. Four albums belonging to and circulated primarily among free Black women during this period have begun to receive scholarly attention; however, Smith’s largely unexamined album offers a unique opportunity to consider how elite free Black women involved in the interracial anti-slavery movement performed their raced, gendered, and classed identities when that performance was addressed primarily to white associates rather than to and for each other. Moreover, as a historian of art and visual culture, I am also interested in the images that Douglass and her peers made in friendship albums because, although they are almost entirely unknown to scholars of American art, they represent the earliest documented signed works of art by African American women.

…a fad among fashionable young women of the period, friendship albums were bound volumes kept by individuals that contained blank leaves upon which the owner’s invited friends would offer gifts of writing or, occasionally, drawings or small paintings.Mia L. Bagneris

Like her peers, Douglass seems to have painted flowers almost exclusively. Part of the culture of sentimentality that defined women’s expression in the nineteenth century, the rise of the “language of flowers” coincided with the popularity of friendship albums in the U.S., peaking between 1830 and 1850, and flower references—visual and verbal—dominated Black women’s contributions to their friends’ album books. To be sure, most of these offerings were fairly mundane expressions of period sentimentality. However, in addition to showcasing her exceptional artistic skill, many of Douglass’s entries convey greater depth than those of her peers, serving as early Black feminist meditations on period respectability politics.

The politics of respectability that informed the lives of all free black Philadelphians particularly dictated the those of elite free African American women who were held to rigorous standards of dress, comportment, and gender-appropriate accomplishment as a public statement of their ladyhood and the fitness of African Americans for full inclusion in American society. This amounted to nothing short of a political act because, as E.W. Clay’s popular Life in Philadelphia cartoons exemplify, for most white Philadelphians, the words “Black lady” constituted an oxymoron. Produced at the same time that Douglass and her peers showcased their ladyhood in friendship albums, Clay’s series lampooned the pretensions of the free Black community, often using buffoonish caricatures of Black women who dared aspire to the title of lady.

Yet, it is precisely to a “lady” that Douglass addresses the pointed puns of her verse on the opening pages of Elizabeth Smith’s friendship album. The artist’s mode of address might be considered simply appropriate for—or even meant to convey deference to—Smith, whose status as a lady would never have been in question. However, in addressing young Elizabeth Smith as “lady,” Douglass’s work also boldly claims the title for herself—as Smith’s friend, granted a privileged space in her album, and as one whose mastery of pictorial and poetic floriography demonstrate her proficiency in the parlance of genteel femininity.

Moreover, the imperative mode of Douglass’s address is also exceptional, both for its boldness and for its transformation of the conventional friendship token into an explicitly political gesture. With her beautiful picture and punning text, Douglass proclaims abolitionism as an unequivocally appropriate vocation for ladies, using the language of feminine refinement to command her audience’s attention to a struggle that convention insisted should not be a lady’s concern. Challenging the popular abolitionist slogan “Am I Not a Woman and a Sister?” Douglass refuses to deal in interrogatives that question her status as an equal; instead, she issues a bold imperative to her white friend, claiming her place as woman and sister, and in so doing, creating a space for the other free Black women who engaged with Smith’s album to do the same.