In 2017, along with colleagues at three other universities in rural Ohio, upstate New York, and suburban Boston, and with funding from Tulane University’s Newcomb Institute, fellow professor in the Department of Political Science Mirya Holman and I surveyed and interviewed over 1,600 children in first through sixth grade about politics. With the help of several Tulane undergraduate students, we set out to examine key features of adult political attitudes in order to identify when and how they form. We also hoped to update the early work on this topic from the 1960s, which indicated kids had positive impressions of politics.

Partisanship has become a defining characteristic of modern politics. Today, partisanship plays a role well beyond candidate selection—significant social divisions, such as where one shops or eats, are even correlated with one’s party identification. Further, scholars have identified an acceleration of negative partisanship, or the tendency for one’s negative beliefs about the opposite party to be stronger than one’s positive views about their own party.

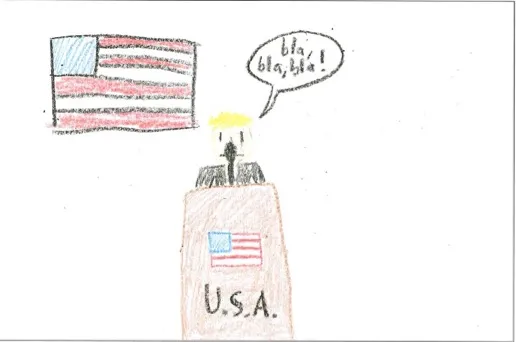

Examining how partisanship operates among children in our 2017 study, we found that the most common response (46%) to questions about which political party one prefers is “I don’t know.” Not surprisingly, older kids were significantly more likely to express a preference than younger children. In fact, approximately one-half of 12-year-olds expressed a partisan preference. We also asked children to draw a political leader so that we could evaluate the effects of partisanship on the image in their minds about politics. President Trump was the most common identifiable person drawn, although many children drew “generic” leaders, police officers, and firefighters. Children identifying as Democrats, Republicans, and Independents were equally likely to draw Trump. However, Democratic kids were much more likely to draw a negative image of Trump than the others; further, Republican kids were not more likely to depict Trump positively.

In these and other tests, we find considerable evidence that for children as young as 10 or 11, partisanship operates like other social identities and is associated more with negative beliefs about out-groups—those that share different interests than the subject—than positive beliefs about in-groups—those that share the same interest or identity. These findings indicate that the seeds of affective, negative partisanship are planted in childhood, a departure from early socialization scholarship that indicated that children had very positive ideas about political leaders, regardless of party. As we enter the 2020 presidential election, it is important to consider what our children are learning from our divisive political climate.