An Aptitude for Transformation: Thinking Beyond the Prompt

Shennette Garrett-Scott, Paul and Debra Gibbons Professor

Originally published in the 2025 issue of the School of Liberal Arts Magazine

I’ll admit it. I’ve never been much of a science girl. My middle-school science fair project was simple: one seed in the sunlight, the other in a dark cabinet. The surprise? The sun-kissed seed never sprouted. Not a leaf. I walked away with a compass I didn’t know I needed: The best questions don’t always stay in their lane. But that spirit of curiosity, unbound by discipline, guides my approach to my scholarship and teaching and to the liberal arts more generally: not choosing between skills or knowledge, but holding both at once.

The either/or trap in the liberal arts debate — between “content” and “aptitude” — flattens not only the education students receive but also the lives they bring into the classroom. Let me explain what I mean through a course I’m teaching this fall on the history of Black women and power. First, I should state up front: The course doesn’t choose sides. Instead, it engages with a bold proposition: Read the lives of those who risked everything to imagine new worlds. Built around life writing — memoir, autobiography, and biography — the course moves between content and aptitude by helping students develop nuanced arguments, write with clarity and conviction, and recognize systems of power alongside possibilities for liberation.

This isn’t just a history course. It’s a training ground for critical thinking and ethical leadership that puts human complexity at the center of learning. From Ida B. Wells-Barnett, the journalist and anti-lynching crusader who helped lay the foundations for both the modern civil rights and women’s movements; to Ericka Huggins, the queer human rights activist and former Black Panther political prisoner who nurtured a radical politics that fused collective justice with personal wholeness; to Tina Beyoncé Knowles, the beauty artist and designer who helped shape global cultural icons and who models Black motherhood as a form of world-making, these life stories don’t offer a set of answers, but an invitation. They don’t just hand students a map; they present a terrain that encourages students to ask harder questions and find their own compass.

In an age of instant answers and prompted thought, the students who flourish both personally and professionally are those who ask the un-Googleable questions, reach beyond algorithms for understanding, think with care and imagination, and tell stories that matter.

Radical Black women’s life writing is not only “content” meant to inspire and uplift. It is a critical mode of inquiry. Take To Tell the Truth Freely, the recent biography of Wells-Barnett. We’ll read it not to admire her but to examine how truth-telling exposes state violence. In this and other works, we’ll trace how grassroots organizing linked the local and global and reshaped ideas about not only leadership but also what counts as political. These texts demand that students confront power and historical memory. They cultivate an aptitude for transformative thinking through a sustained engagement with complex lives and ideas.

In other words, students don’t just read biography, but practice it. Through learning activities that include critical analysis and digital storytelling, students craft projects grounded in rigorous research and their own lived experiences. No prior tech skills required; just curiosity and a willingness to learn.

I encourage students to make both emotional and intellectual investments in their learning and offer creative flexibility to communicate ideas that matter to them — all hallmarks of a liberal arts education. Our work together practices historical thinking, humanist reasoning, and real-world inquiry to move beyond prompted answers, to ask deeper, more self-aware questions about ourselves and the world around us.

To be clear: Content matters. These biographies are rich with archival, historical, and theoretical knowledge. They’re global in scope, interdisciplinary in method. But skills like intellectual risk-taking don’t grow simply from being exposed to complex works. They’re built through context and reflection.

Students need room to confront their own uncertainties, personal biases, and privilege; space to wrestle with and grow into their work. The liberal arts offer the space to cultivate ways of thinking that expand beyond any single field. Courses like this one offer a model for learning to think in ways that are both disciplined and expansive.

That plant I left in the sun for my science fair project never grew. But the one in the dark cabinet did, against all odds. Maybe the conditions we assume are ideal aren’t what help us grow. In an age of instant answers and prompted thought, the students who flourish both personally and professionally are those who ask the un-Googleable questions, reach beyond algorithms for understanding, think with care and imagination, and tell stories that matter. A class like mine won’t teach you what to think, but it’ll help you think ethically and historically.

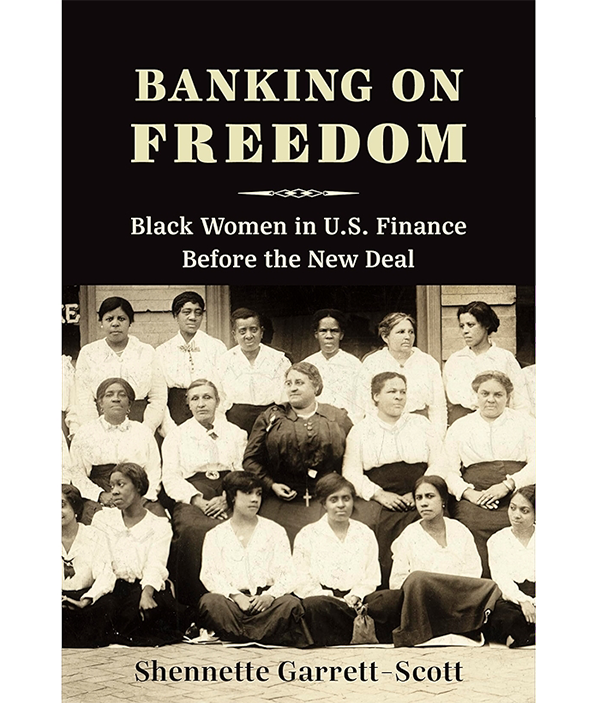

Shennette Garrett-Scott is an associate professor in History and Africana Studies, and the Paul and Debra Gibbons Professor in the School of Liberal Arts. She recently won the 2025 Frances “Frank” Rollin Fellowship for her project, Titan: The Life of Maggie Lena Walker, a biography of the pioneering early 20th-century financier and civic leader. She is the author of the award-winning Banking on Freedom (Columbia, 2019), and her second book, Black Enterprise: How Black Capitalism Made America (W.W. Norton), is forthcoming.