Mastering Unstructured Problems: The Liberal Arts Advantage

The liberal arts, and especially the humanities, are important for everyone. Although the specific disciplines included under the umbrella of liberal arts have evolved over time, they have been a significant part of higher education for more than a millennium. The term “liberal arts” derives from the Latin for “free” (liber/liberalis) and “skill/practice” (ars/artes) because these studies were essential in preparing free citizens for life as leaders in their communities. This is just as true now as it ever was — perhaps even more so. We live in a world where movement around the globe and interaction with international communities is easier and more frequent than in the past. In this world, the liberal arts offer ways of engaging with other cultures through its variety of disciplines. In addition, the liberal arts prepare one to work through “unstructured problems” and to understand specific issues within a broader context — the “big picture” view.

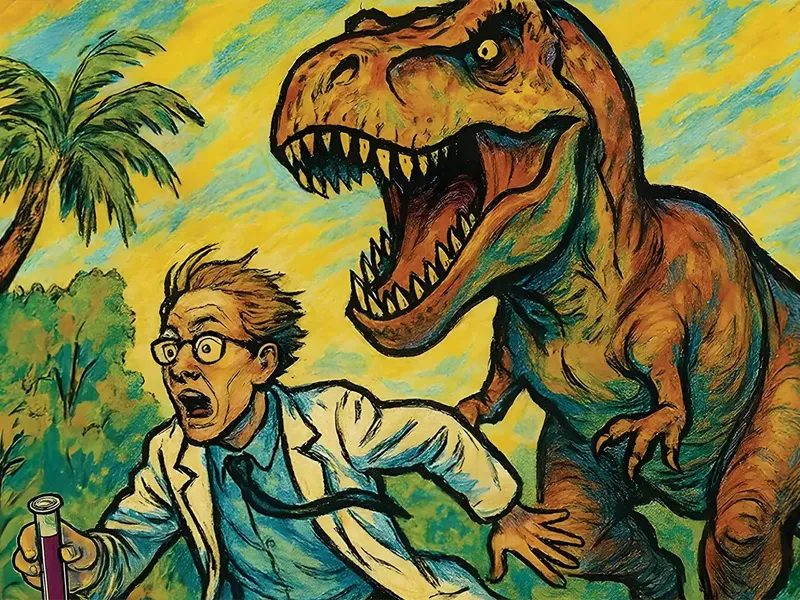

Science can teach you how to clone a dinosaur. Humanities can tell you why this might be a bad idea.

The expanded worldview has many advantages. In recent years, the benefit of higher education itself has been questioned, especially the value of the liberal arts. The best argument in favor of a liberal arts education is that it supports and encourages creativity. All the liberal arts disciplines encourage students to think about complex issues for which there are often no specific rules or frameworks. The outcome is that the student learns how to develop strategies for dealing with the “unstructured problems” of the world. Most of the challenges that we confront in our lives are not neatly packaged with rules and instructions on how to fix them. In the liberal arts, you prepare yourself to think deeply and in a more constructive way. Moreover, learning how to approach the unstructured research problems presented in the liberal arts curriculum outfits you to become a lifelong learner, someone capable of adapting to new situations and problems. In other words, you are learning how to learn, not just mastering an array of facts.

A frequent concern expressed in higher education revolves around preparing students for the jobs of the future. How will we know what those are? The world as we know it is changing rapidly, and it may not be possible to predict what will be needed 10 or 20 years from now. Progress seems so rapid that we are outpacing our ability to consider its implications. A meme from a few years ago (“Science can teach you how to clone a dinosaur. Humanities can tell you why this might be a bad idea”) suggested that the liberal arts, particularly the humanities, could — indeed should — have a role in dealing with new technology. The key to preparing for the unknown is developing a flexible mindset grounded in reason, ethics, and creativity. If you immerse yourself in the liberal arts, you are equipping yourself with skills that last a lifetime and prepare you for nearly anything.

The liberal arts, and especially the humanities, are important for everyone. Although the specific disciplines included under the umbrella of liberal arts have evolved over time, they have been a significant part of higher education for more than a millennium. The term “liberal arts” derives from the Latin for “free” (liber/liberalis) and “skill/practice” (ars/artes) because these studies were essential in preparing free citizens for life as leaders in their communities. This is just as true now as it ever was — perhaps even more so. We live in a world where movement around the globe and interaction with international communities is easier and more frequent than in the past. In this world, the liberal arts offer ways of engaging with other cultures through its variety of disciplines. In addition, the liberal arts prepare one to work through “unstructured problems” and to understand specific issues within a broader context — the “big picture” view.

The expanded worldview has many advantages. In recent years, the benefit of higher education itself has been questioned, especially the value of the liberal arts. The best argument in favor of a liberal arts education is that it supports and encourages creativity. All the liberal arts disciplines encourage students to think about complex issues for which there are often no specific rules or frameworks. The outcome is that the student learns how to develop strategies for dealing with the “unstructured problems” of the world. Most of the challenges that we confront in our lives are not neatly packaged with rules and instructions on how to fix them. In the liberal arts, you prepare yourself to think deeply and in a more constructive way. Moreover, learning how to approach the unstructured research problems presented in the liberal arts curriculum outfits you to become a lifelong learner, someone capable of adapting to new situations and problems. In other words, you are learning how to learn, not just mastering an array of facts.

A frequent concern expressed in higher education revolves around preparing students for the jobs of the future. How will we know what those are? The world as we know it is changing rapidly, and it may not be possible to predict what will be needed 10 or 20 years from now. Progress seems so rapid that we are outpacing our ability to consider its implications. A meme from a few years ago (“Science can teach you how to clone a dinosaur. Humanities can tell you why this might be a bad idea”) suggested that the liberal arts, particularly the humanities, could — indeed should — have a role in dealing with new technology. The key to preparing for the unknown is developing a flexible mindset grounded in reason, ethics, and creativity. If you immerse yourself in the liberal arts, you are equipping yourself with skills that last a lifetime and prepare you for nearly anything.

Training prepares you to deal with the known. Education prepares you to tackle the unknown.

(Adapted from Thomas Ricks, The Generals, 2012)

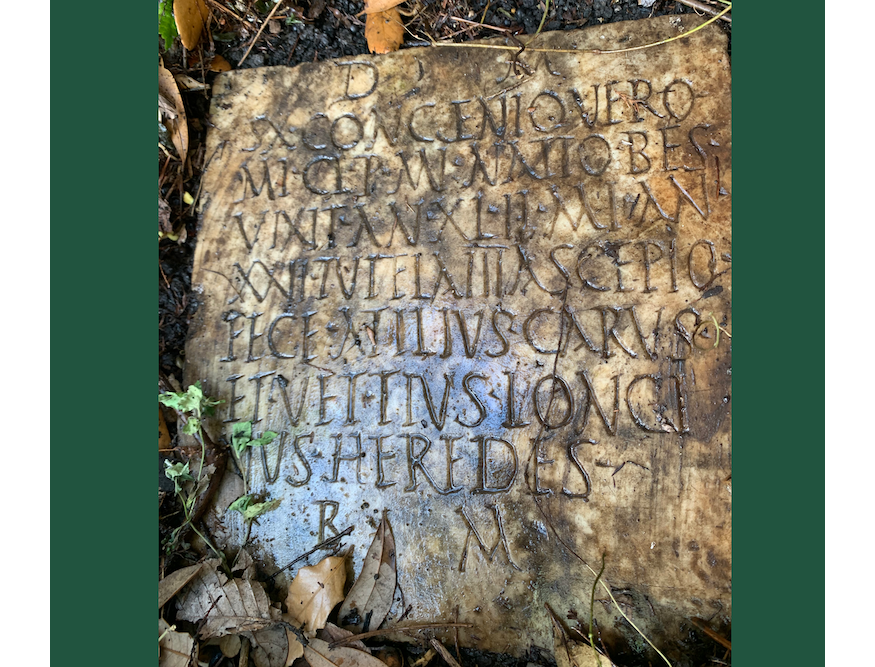

Susann Lusnia is an associate professor in the Department of Classical Studies. She specializes in Roman art and archaeology, and teaches courses in Roman art and archaeology, Pompeii, Etruscans, Roman painting and mosaics, and topography of Rome. Lusnia recently gained worldwide attention after translating a Roman artifact that was discovered in the backyard of a New Orleans home.