Mexico. Take a moment to think about the movies and images you have viewed that reference groups of people in the history of Mexico. You may recall images of the Aztecs, the Mayans, or Spanish conquistadors. These images present conflicts between a Spanish and an indigenous past: two roots that fused to form a national identity. Yet, in other Latin American countries the images of the nation incorporate a third root: African descendants. African influences are seen and felt in Brazil from Candomblé to Capoeira; in Cuba through Santeria and Salsa; and in Peruvian music and their Pacific coast communities. The African presence extends through Colombia, Ecuador, Panama, Venezuela, and throughout Latin America.

Despite the dominant narrative, African descendants also have a history and presence in Mexico. In 2015, the Mexican government conducted an interim census that incorporated African descendants into the categories of race and ethnicity, which had not been done since the 1830s. Citizens had the opportunity to self-identify and almost two million people identified as African descendant. After the results of the 2015 census were released, media outlets immediately questioned where African descendants in the interim census came from, some speculating that they were recent immigrants from West Africa or from the Caribbean.

Mexico was a slave trading country in the 16th century, having a population of around 200,000 principally West African slaves that outnumbered the Spanish colonialists for decades and was for some time the largest in the Americas. Black slaves were typically used by the Spanish to act as foremen, overseeing the Indigenous populations, and many of the (mostly male) slave population went on to marry Indigenous women. Therefore, and due to the many resulting mixed-race offspring, Black Mexicans were all but forgotten about for centuries, as their bloodlines mixed with other Indigenous communities and Mestizo peoples of Mexico.

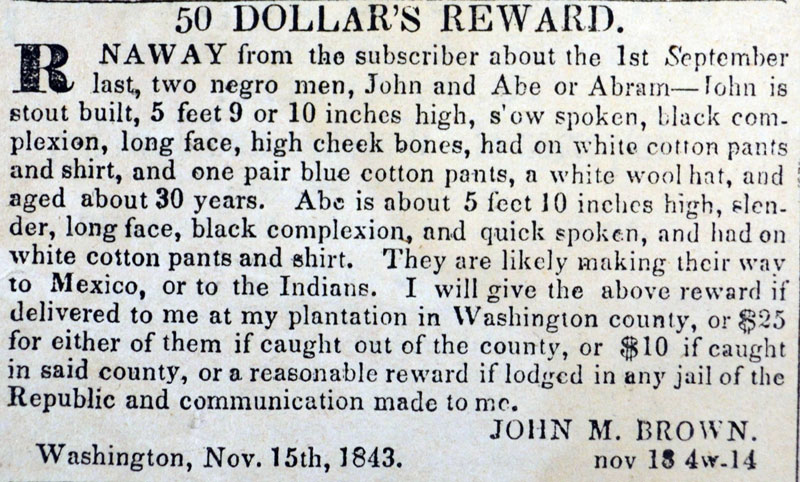

The longer history was little appreciated. In the 1500s and early 1600s, New Spain (colonial Mexico) had one of the highest importation rates of enslaved Africans to the Americas leading to large populations in cities. In their first decade of independence, the Mexican government abolished the slave trade in 1824 and the institution of slavery in 1829. As a result, countless African Americans in the southern U.S. took advantage of this new law and participated in the southern route of the Underground Railroad fleeing to their neighbor, Mexico—quite contrary to the standard narrative of slaves seeking freedom north.

Despite the dominant narrative, African descendants also have a history and presence in Mexico.

For example, on July 7, 1839, twenty-seven passengers boarded a merchant ship in New Orleans. They exited the ship in the Mexican port city of Tampico. Among the passengers were seven African Americans whose passport status in Mexico listed them as enslaved. These African Americans had traversed the Gulf, hidden on a merchant ship that took them from enslavement in the U.S. to newfound freedom in Mexico. They practiced their own agency and took advantage of the abolition of slavery in Mexico. Passport records of New Orleans from 1830 to 1840 combined with Mexican importation logs reveal a significant number of enslaved and free African Americans who moved to Mexico.

Many of the African Americans remained in the port cities and found employment in the shipping arena and marketplaces, joining the African descendant communities already present in Mexico. African descendants contributed to society in various ways, including through their occupations as dock workers, vendors, in the military, and as shop owners, and became integral to every aspect of life in Mexico from their roles as political participants, to religious and artistic capacities.

East Texas Digital Archives/Stephen F. Austin State University.

As African descendants received state recognition in the interim census of 2015, and will be included going forward, the census should be used to do more than count their numeric presence. The Mexican census can help politicians, lawmakers, and citizens carefully assess issues affecting African descendants, such as access to resources, education, and other critical aspects of life throughout Mexico, which many communities are fighting for today. Although there seems to be minimal representation of Afro-Mexicans, the art of historical research challenges us to consider the past in connection with current-day circumstances to illuminate the “invisible,” not only to reveal the vibrant history of Afro-Mexicans, but to enhance the quality of life of present-day citizens as a model for social justice work for other forgotten groups and spaces.

Beau D.J. Gaitors earned his Ph.D. in history from Tulane in 2017. His dissertation focused on traders in Veracruz during the transition to Mexican independence. He is an assistant professor in the Department of History at the University of Tennessee in Knoxville, where he teaches Latin American history.