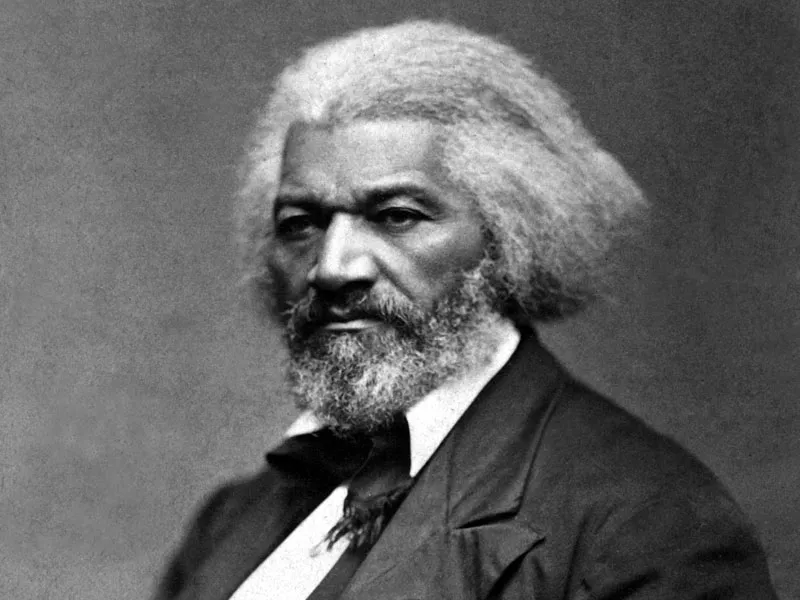

The tail end of Black history month in 2021 saw what, at first blush, seems a most curious and unwelcome announcement. The same techniques being used for deep fake technology (the processing power of digital software and machine learning) have just been used to animate, among other historic figures, Frederick Douglass. It is perhaps a fitting tribute to the most photographed man of the nineteenth century, who believed that photos transmitted “the essential humanity” of their subjects, that we should be able to see Douglass come to life. The truth is that from the moment Douglass rose in the audience of the Nantucket Atheneum in 1841, Americans were struck by how he animated abstract debate; he was the living personification of the pursuit of the nation’s freedoms. Living proof of his republic’s hypocrisies, Douglass was also as compelling and inviting in every dimension as slavery was designed to be impenetrable. When Douglass published his first autobiography in 1845, the book became such a massive bestseller that its author was forced to go to Britain to avoid being reclaimed by his former master.

Ever failed.

No matter.

Try again.

Fail again.

Fail better.

-Samuel Beckett

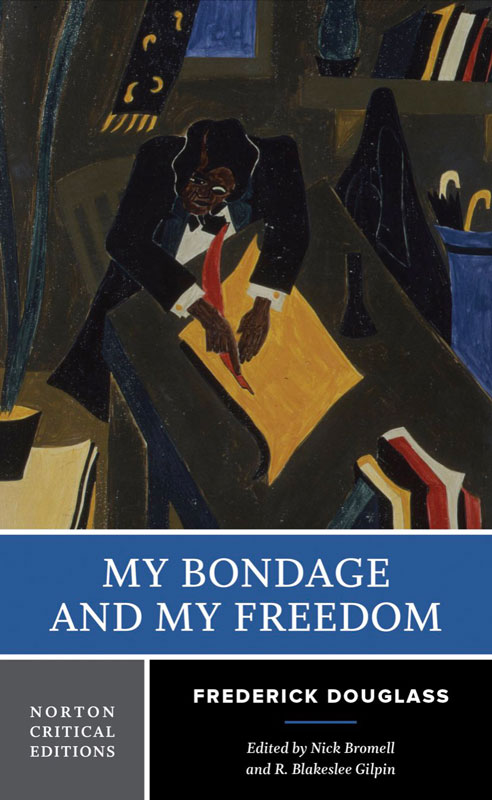

Douglass’ supporters soon purchased his freedom for $711.66, and Douglass spent his life as a singular stylist of prose and tireless campaigner on behalf of his enslaved brethren. Douglass was, above all, a passionate and skeptical patriot. To be sure, unbridled anger pulses through his 1852 speech “What to the slave is the Fourth of July?” and bottomless tragedy punctuates his 1845 Narrative, particularly the staggering metaphor of his enslaved younger self watching ships freely plying the Chesapeake Bay. But when he published an expanded and revised autobiography (the second of three!) My Bondage and My Freedom in 1855, Douglass offered his life as evidence for his country’s foundational contradictions, a story of an enslaved boy gaining the most sacred tool of democracy: words.

Across thousands of speeches and newspaper editorials, a lifetime spent with word and deed, Douglass personifies Samuel Beckett’s sublime adage: “Ever tried. Ever failed. No matter. Try again. Fail again. Fail better.” Failing better was Douglass’ message and his living example. Revising himself and his republic was the only way to reach toward the nation’s higher ideals.

As America’s history of racism and white supremacy saturates our current moment, my and my colleague Nick Bromell’s new edition of Douglass’ My Bondage and My Freedom highlights the author’s earnest desire for us to be better citizens. Reading it implores Americans to listen, to learn and unlearn, and to fail better.

The newest edition of Douglass’ My Bondage and My Freedom, edited by Gilpin and Nick Bromell, was released in 2020 by W. W. Norton & Company.