Originally published in the Summer 2022 School of Liberal Arts Magazine

Monday, August 15th, 2022

The Tenenbaum Sophomore Tutorials bring together faculty and students in small group discussions, creating an opportunity to explore intellectual passion while engaging in humanistic research. The program incorporates individual tutorials to allow students to pursue independent projects in the Humanities and Humanistic Social Sciences. Students are encouraged to go beyond traditional material as they team up with a Liberal Arts faculty member who mentors and guides their research.

During the Spring 2022 semester, professors Edwige Tamalet Talbayev and Asmaa Mansour co-created a course called “Home and the World: Diasporic Arab American Experiences.” What follows is a conversation between the two and one of their students, Shreya Srigiri (SLA ’24), about the collaborative nature of the program and the kind of learning it encouraged.

Shreya Srigiri (SS): One of the strongest components of this class for me was how you both presented the material, with every contributing source adding perspective. What is your connection to diasporic Arab American experiences? What made you want to teach this topic?

Edwige Tamalet Talbayev (ETT): The Arab immigrant experience I teach and know best is the immigration from the North African region—the Maghreb—to Europe, which is framed very differently [than this]. In our class, I wanted to look further into diasporic Arab communities in a U.S. context, to examine the issue of migration and exile comparatively, beyond immigration to Europe.

Asmaa Mansour (AM): I believe in making the humanities purposeful, and I believe that in teaching what we teach, we push students to re-think some of their misconceptions and examine their implicit biases or pre-existing stereotypes. I wouldn’t want to change students’ views, but rather create a safe space for them to think critically and perhaps envision a world free from hegemony, racial discrimination, and social injustices.

SS: One of the main differences with the Tenenbaum Tutorials, juxtaposed with my other classes, is the one-on-one time I get with you as my professors. The foundation of this class is collaboration, so I would like to ask what collaboration truly means to you.

AM: Co-teaching in general requires a lot of trust and respect. It is like sharing your chocolate cake!

ETT: Ha, very true.

AM: Creating something valuable with my colleague and being able to share that with students interested in the material is something I am so grateful to have experienced. As an early career scholar myself, I want to thank you, Edwige, for your support throughout this class, for giving me space to lead without creating an imbalance. I have definitely learned from your style of teaching. It has been a wonderful experience to see how we have progressed throughout the semester, and it felt very natural.

ETT: Definitely. There was an organic flow between us. Even with different interpretations and teaching styles, we reached a sort of balance. Working collaboratively has helped foster even more collaboration, and it has opened up new space for participation.

SS: The ideas we covered are very raw, uncomfortable concepts, including race, gender, sex, prejudice, stereotypes, and religion. Being able to have these conversations is a privilege, and it is a representation of higher education: having the space to delve into existing dichotomies and interpersonal relationships that contribute to the world we live in today. I believe it was also reflected in the class visits that gave us more insight into primary sources, such as from Professors Matt Sakakeeny, Marie-Pierre Ulloa, and Nadine Naber. How do you believe this Oxford-tutorial style teaching to be integral to the kind of perspective this class provides?

ETT: The format works to foster individualized feedback. The teaching during tutorials adapts to student interest and follows each student's own pace. This is not a top-down process with instructors imparting knowledge. In this class, each student is placed front and center, and this sense of accountability fosters independence and future collaborative skills, such as the responsibility to come prepared, and to demonstrate a certain degree of professionalism within tutorial meetings.

I think both of us had very similar outlooks on how we wanted to guide learning. We were adamant to stay away from any sort of political indoctrination. Instead, we drew on our literary training to encourage individual interpretations of texts and contexts, and agreed the work of critique in the classroom was to take center stage. We would give pointers, correct logic and arguments, provide contextual and historical feedback, but were always mindful to not impose our own world view. This may be the most resonant form of collaboration—the one we developed with students, individually and as a group. The idea was to think together even if we disagreed, to have a generative dialogue despite diverging opinions.

AM: I think the class structure gives an individualized experience, where you get to know students and how they work, and also goes beyond just talking about assignments, as the focus is really on the challenges they face. We designed a syllabus that helped students develop a cross-cultural understanding of different ways of living and knowing.

SS: The tutorials really extend their impact into the classroom and have called for this dynamic shift of authority that is necessary to bring about quality discussions in our seminars. The shift from professor to mentor really contributes to the standard required within the classroom, as the topics bring about a constructive dialogue between everyone.

ETT: The idea for us when conceiving this class was to create the context for inquiry where all students get to shed prejudice and get out of their comfort zone in a respectful, collaborative way. To reach across cultural and religious differences, to really hear others’ perspectives, others’ experiences, and to get a chance to exchange ideas with students they would not necessarily encounter during their time at Tulane. We work toward understanding common values, and work against what could be barriers. Regardless of our backgrounds, and the fact that we may not agree most of the time.

SS: Definitely, we do not always agree.

ETT: We aim to help students move beyond media narratives and facile dichotomies. We wanted them to hear things from the perspective of this Arab American community which was invisible for so long—as evidenced by the fact that there isn’t an Arab American box on the census form to this day. This is a very powerful mission statement for us, one that provides an opportunity to formulate reparative steps.

AM: Definitely, we wanted to ease students’ apprehension, where they are eager to learn about Arab American culture but may worry about being offensive. This makes me feel that things are changing, that students are invested and ready to talk about sensitive topics, but just need the encouragement to take the initiative and feel comfortable asking questions. I always ask questions and make sure students’ voices are heard and respected, especially when they talk about generally unfamiliar topics or pronounce complex Arabic terms.

Regardless of background, I encourage inquiry. In this way, we bring the theoretical into the practical, and interlink the personal with the political. While most of my students have different positionalities and experiences, I take pride in seeing them center the voice of the Other instead of being the mouthpiece for them. We ultimately move away from “exoticizing” or “saving” the Other to “using” whatever privileges we might have to uplift and establish solidarity with these groups.

Audre Lorde once said: “your silence will not protect you.” This class has broken the silence about the intersection between race and politics, Islam and gender/sexuality, “Islamic” terrorism, the immigrant experience, etc. From banal experiences such as names being mispronounced, to considerations of what a “real” American is.

SS: It’s why diversity is important. My classmates being genuinely interested in the realities of a second-generation immigrant has been very validating of my experience and has achieved a sense of visibility. Not many professors are able to make that happen in their class. Which leads to the question, as you mentioned Professor Mansour: are we talking about Arab American experience or are we talking about the American experience? This country is built on immigration. Immigrants are a part of what this country is, which is reflected in large city hubs such as New York, Chicago, and Los Angeles. This class was the first time I felt I did not have to prove that I am a part of America. And this was exhibited in the beauty of my classmates trying to interact with difficult issues, not side-stepping them.

ETT: This is a forum to consider what we have in common across groups, to theorize potential coalitions. We are talking about Arab American identity narratives, but we also look beyond the U.S., at the transnational arcs of these diasporas, at the world from which they come. This is also thinking of ourselves and our lives in this global framework, as always being part of something beyond our most immediate environment.

SS: Are there other classes at Tulane that focus on Arab culture?

ETT: Of course! One of the objectives of this course was to show how these Arab American experiences connect back to the vibrant culture of the Middle East North African region. Our brand-new MENA Studies program offers a variety of courses across the disciplines that illuminate the historical, linguistic, cultural, and political complexity and richness of this region.

AM: “Home and the World” has inspired students to think of MENA countries not as alien, faraway places, but rather countries relevant to the United States.

SS: In the end, we are all much closer than we think. This class gave us not just content topics but how to approach important subjects in a respectful setting, which is an invaluable skill. I want to be able to talk about issues like this head on in my career. I am a creative writer, and the material has been so personalized that I’ve been inclined to exhibit what it meant to me through art; more specifically, poetry.

ETT: And as a teacher, your response to our class, Shreya, has been one of the most rewarding moments for me. The fact that it became this ontological experience for you, that it spurred you to write poetry and to feel enough trust to share it. This kind of connection has happened a few times in my career, but not that often. I cherish those moments.

Spring 2022 Student Submissions

“I am a woman of color, and this class has helped define my space not only here at Tulane, but in the world, too. It has been one of the most liberating, memorable, and meaningful experiences for me as a student. I am a creative writer, and the material has been so personalized that I was inclined to exhibit what it meant to me through art; more specifically, poetry.”

– Shreya Srigiri, SLA '24, poem below

Home

By Shreya Srigiri

Where do I call you?

Shall I search for you in the coconut oil my grandmother

Pulls through my long, dark lock of hair,

as the jasmine flowers sway to the tune of the tabla.

Finding the beauty in the rhythmic

patting of my carnatic teacher’s hand took me years,

as I sit at twenty years old,

yearning to hear her voice lull my restless heart.

I stare at your face, no crookedness to your nose, eyes bluer than the sky we walk under. My darker sisters running their hands through my hair, whispering about the strength it endures. Where do I fit into this, this dichotomy of beauty and pain, walking the same path, yet catching his blue eyes searing into my hips,

my waist as I dance to the rhythm of my breath,

his gaze scorching the flames of my heart.

But the sky eventually meets the horizon, and you will always find your way to her soft, blue eyes, leaving mine burning in the sun’s angst.

You lust over the curves of me and my darker sisters, yet you slight the weight of our scars, as you claim they are too rigid,

too deep.

The grief you inflict upon me leaves me craving the comforting heartache I have carried from generations of women past, as that path of hot stones is one familiar, pricking my every step.

I found abandonment, reflected in your glassy, striking blue eyes,

and a sweet sorrow in the scent of jasmine floating from oceans wide,

Where do I call you?

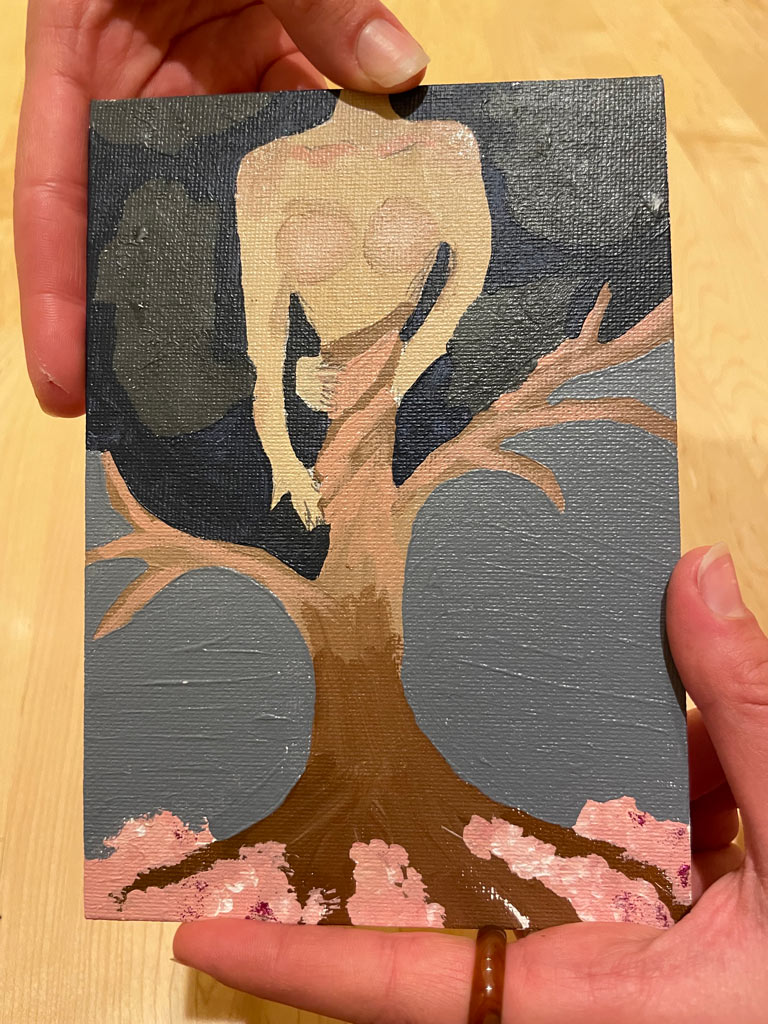

“My painting signifies surviving an experience of sexual violence. The tree intertwined with the body portrays growth intertwined with suffering. The dark skies at the top contrast from the blooming field of flowers below, and in between is a gray hue with clearly messy strokes—as the middle part of healing is a gray area that can feel messy. The choice of gray also speaks to the “gray area” of consent, when an experience can be confusing and cause pain. Though hard to see, sparkles on the chest signify resilience and body autonomy.”

— Anna Johnson, SLA ’24

Middle East and North African Studies

Meet the MENA Studies faculty whose diversity offers a wide array of coursework in this complex region’s past and present, and explore upcoming classes, events and study abroad opportunities.