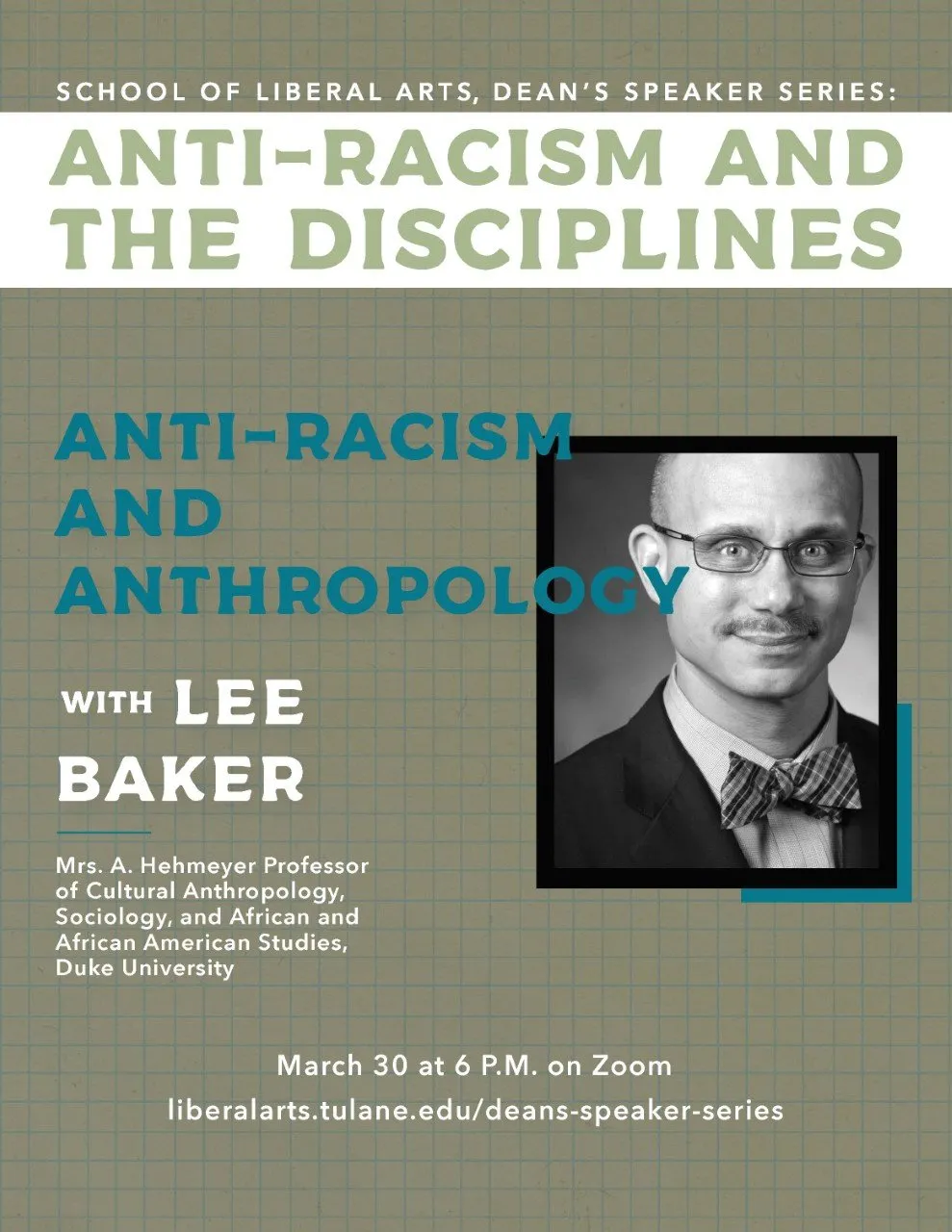

“If anthropology remains ascribed and confined to the white-supremacist models of ‘anthro-fathers’ past, we will not survive the twenty-first century,” I thought as I listened to Dr. Lee Baker issue warnings of our anthropological future. Dr. Baker, the Mrs. A. Hehmeyer Professor of Cultural Anthropology, Sociology, and African and African American Studies at Duke University, implored that we take heed of where anthropology has been, where it is now, and where it has the potential to grow during his lecture this March as part of the School of Liberal Arts Dean’s Speaker Series, Anti-Racism and the Disciplines.

After an impressive review of his scholarly work, Dr. Baker began his presentation by placing race, Americanization, and immigration within the racialized historical context of the United States and the discipline of anthropology. Utilizing stories of assimilation, Dr. Baker spoke about legislation that essentially institutionalized racial ideologies, which, in turn, aided in the creation of complex notions of who can and who cannot be or become an American. To explain this more deeply, Dr. Baker pointed to the color-blind racism that has often been used to hide our current societal predicaments stemming from centuries of differentiations among those who are Black, Indigenous, Latinx, Asian, and other peoples of color and equating whiteness with Americanness. He also highlighted our anthropological history by discussing how famous anthropologist Franz Boas’ optimistic and naive attempt to erase racism was executed by measuring and quantifying immigrants in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century as well-intentioned. However, this attempt was problematic, as Boas aimed to dismantle racial hierarchy, pseudoscience, and eugenics through race amalgamation and miscegenation.

Like Boas, anthropologists today struggle with well-intentioned research within institutions that come with their own veils of racism. Many of us are well aware of the role anthropology has played in aiding ideologies of difference, and while we are explorers and reckoners of the past and present, Dr. Baker challenges us to also look to the future of anthropology through a two-fold approach. First, we must keep asserting counterhegemonic and decolonial approaches in the discipline and throughout other vehicles of information. Second, we must recruit future anthropologists of color so as not to fall into the trappings of structural and institutional hierarchies of difference. We must remain vigilant in maintaining relevance to society and its changes.

All of my senses were engaged as I listened to the infectious passion of Dr. Baker and the brilliant moderator Dr. Sabia McCoy-Torres, a professor in the School of Liberal Arts Department of Anthropology, as they discussed the future of Anthropology. As a graduate student focusing on Afro-Puerto Rican aesthetics in the Chicago diaspora, it is imperative that the future of anthropology become inclusive of “othered” populations that are in our own backyards and how anti-racist dialogues such as Dr. Baker’s are pertinent to our understandings of a historically constructed American authenticity. As someone who has experienced macro- and micro-level aggressions I understand that racism is alive in the United States, and while misinformation has created the term “post-racial,” what we have learned from the past and what we see in current events around the country is that racism adapts to resilience. This does not need to be our future. While we cannot change anthropology of the past, we can contest it and rewrite the anthropology of the future as we attempt to decolonize, interrupt, and create a more equitable interdisciplinary field of study.

Laura M. Nieves is a second-year doctoral student in cultural anthropology at Tulane University's School of Liberal Arts. She received her Master’s in Latin American and Latino Studies at the University of Illinois at Chicago and her undergraduate degree at Northeastern Illinois University. Nieves’ work encompasses issues of race, gender, and class in the Puerto Rican diaspora of Chicago with a focus on Afro-Puerto Rican dance and other artistic cultural aesthetics.