For the greater part of the twentieth century in China, film projectionists did not work quietly behind soundproofed projection booths where they attended to the hidden machinery of cinema’s dream factories. Until the proliferation of television during the 1990s, motion pictures reached the countryside thanks to mobile projection teams, which transported film projectors, film prints, sound equipment, and electric generators across the nation’s variegated geography. Film screenings never stood alone, but instead were accompanied by lectures, community activities, news reports, and government propaganda. Newspapers, magazines, and radio programs celebrated the heroism of itinerant projectionists, whose jobs involved long tours away from home, strenuous physical labor, and diplomatically negotiating the rifts between state policy and local society.

Although greatly expanded under the Communists in the 1960s, state-sponsored mobile film projection originated in the 1930s when the ruling Nationalist government made use of new portable film technologies to build a nationwide educational projection network. Proponents of educational film saw movies not only as a powerful tool for indoctrination and pedagogy, but also as a medium that could connect diverse communities by supplying them with shared objects and experiences. Chinese reformers in the 1930s saw the country as underdeveloped: its transportation infrastructure was fragmented, and its population did not understand themselves as being part of a unified nation. Film projectionists overcame these obstacles by transporting films via automobiles, boats, animal drawn carriages, and by foot. They lectured alongside their films—sometimes in local dialect—to make them accessible to culturally and linguistically diverse audiences.

Who were these itinerant projectionists? Ministry of Education-sponsored training programs envisioned their candidates as committed educators who were physically able and equipped with foundational knowledge in mathematics and the sciences, as well as fluency in English (as most educational films and film equipment used in this period were imported from the U.S.). While we often think of film projectionists as specialized technical workers, such “projectionist-lecturers” had to be jacks-of-all-trades. Bringing together diverse talents, they also became figureheads of national integration.

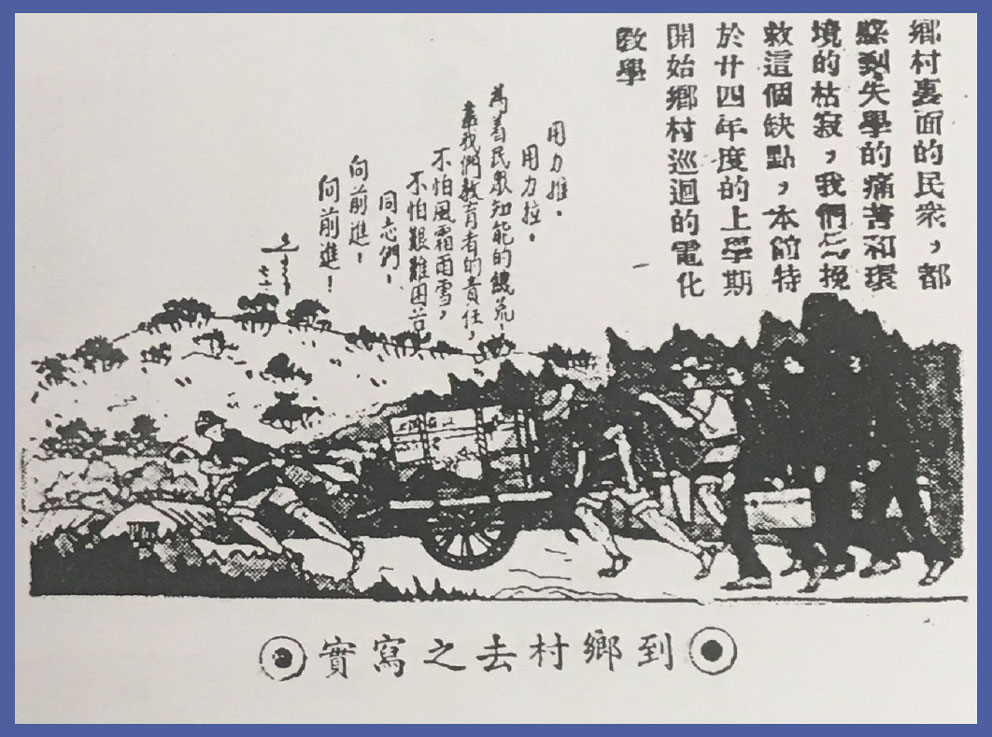

A print illustration from 1937 (below) exemplifies the complexities, and indeed the contradictions, of the image of the projectionist as a heroic and multitalented individual. Beside a team transporting film equipment on a hand-drawn cart against a background of rolling hills is a poetic inscription written in the cadence of a work song, eulogizing the travails of projection teams:

Pull Hard! Push Hard!

In the name of the peoples’ intellectual hunger

This is our great educational responsibility

Not afraid of the wind or the frost, the rain or the snow

Not afraid of the grueling hardships

Comrades!

Forward March!

The poem celebrates the heroism of film projectionists by evoking the physical hardship that they endure. The projectionists’ ability to brave the elements is taken as a sign of their commitment to educating the people and improving society. Yet, in the illustration itself, we see a clear division of labor: the most prominent figure in it is a worker with bared legs straining to pull the cart while the group of the projectionist-lecturers follow in black suits and suitcases. This stark contrast between the “manual” and “mental” labor of film projection belies the poem’s singular “we.” Who exactly is it that bears “our great educational responsibility?”

While it is commonplace today to say that media technologies disconnect people from their physical environs while enabling them to form new communities irrespective of geography, the experience of Chinese film projectionists suggests that this is only one side of the story. Mass mediated societies remain bound together physically and geographically by uneven systems of material circulation and human labor, of which the projectionist is one part. In this context, perhaps we can read the projectionist’s “great educational responsibility” neither as a commitment to an abstract idea or cause (the “nation,” in this case) nor as the completion of a narrow professional task, but rather as the process of attending to these systems in their complexity.