What it Means to Be an American Writer

By Evan Allbritton

As the saying goes, the best writers write what they know, and for a new generation of writers faced with defining what it means to be an American, this statement could not be more important.

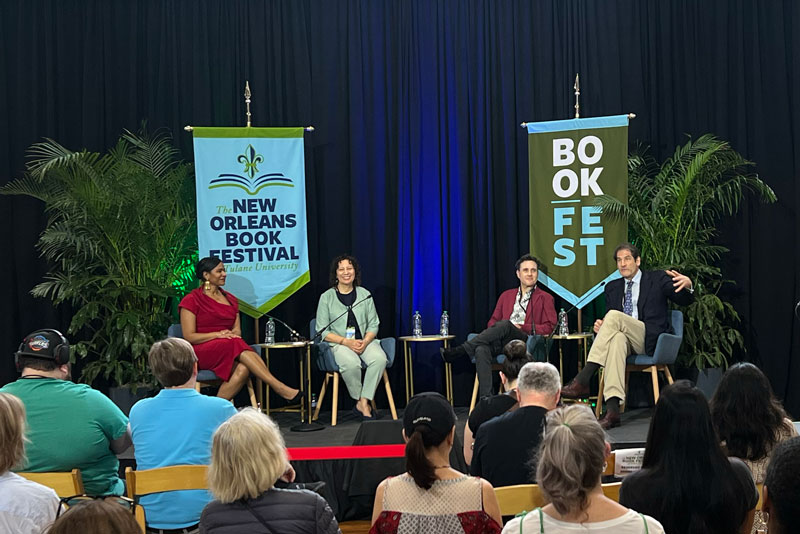

This year’s New Orleans Book Festival succeeded yet again as a vibrant hub for all things arts and culture — highlighting stories from local writers and internationally acclaimed authors alike. Through this constant hubbub of unique events, though, Book Fest was able to incorporate a common question into every panel I encountered: what does it mean to be a writer in modern America?

To begin my Book Fest journey, I first sat in on “The Atlantic Conversations” on Thursday evening with Book Fest Co-Chair and Tulane School of Liberal Art’s own Walter Isaacson and Editor-in-Chief of The Atlantic, Jeffrey Goldberg. The panel centered on The Atlantic’s curated list of “The Great American Novels,” opening up a lively discussion of what it means to represent American life through writing. Including a diversity of work from the 1920s to the present, Goldberg stated that “The Atlantic tries to expand what an American writer is,” and has always tried to feature a vast array of beliefs and identities in its publications. Even today, the so-called “greatest” American novels fall within the literary canon, a white, male-centered narrative that does not reflect the realities of American life. However, “the founders of the Atlantic never tried to define what the American idea is,” Goldberg said, expressing his belief that it is each generation’s job to define and radicalize the American idea to fit our current moment. By rejecting the notion of the literary canon, The Atlantic’s work illustrates that being an American is not a stagnant idea, but rather a constantly changing group of identities that a new generation of writers must work to explore.

“Voices of the South: A Conversation," featuring authors Imani Perry, Clint Smith, and Tulane School of Liberal Arts Professor of English and the Andrew W. Mellon Professor in the Humanities Jesmyn Ward, on Friday afternoon offered another angle to the question of what it means to be an American writer. Focusing especially on southern politics, what it means to be Black in America, and how to use your experiences to write for social justice — these incredible scholars emphasized the importance of writing in forming American identity. On discussing the grave legacy of slavery in the American South, for instance, Imani Perry stated that “part of the management of grief is storytelling.” By reckoning with the unspeakable past of America, writers must involve themselves with these difficult questions in their work and write what they know. Additionally, Perry described that, for her, being a Black American writer means not simply calling out the injustices of America’s past, but celebrating her own identity as a black southerner, saying that “you have to engage with the wound and with what has healed you. It is both.” Through discussing identity, Perry’s and the rest of the panel’s moving sentiments illustrated the power of writing and conversation as an agent for change.

This year’s Book Fest did an excellent job of fostering spaces for a diversity of thought. Speakers eloquently argued for writers to be agents of change, to be unafraid of celebrating personal experiences, and to ask the difficult questions. So, as a new generation of young American writers and thinkers are born, it is more important now than ever to continue writing to reconstruct and define what it means to be an American in our current moment.

Evan Allbritton is a member of Tulane University’s Class of 2027, majoring in English and Political Science. On campus, she is a staff writer for The Tulane Hullabaloo and plans to pursue journalism.

Family & Storytelling: Jamila Minnicks on Moonrise Over New Jessup

By Alya Satchu

New Jessup, Alabama was an all-Black town that was reluctant to racially integrate, to protect Black social change, progress, and advancement. It was 1957 when Alice Young moved into this society determined to preserve and reinforce their community and the network within it. There, she met and fell in love with Raymond Campell, who frequently engaged in secretive activities that went against the collective values, normalities, and objectives of New Jessup’s culture. As their relationship grows stronger and Raymond’s activities intensify, their place in New Jessup is threatened. Throughout the book, Alice struggles with prioritizing either the safety and security she found in her New Jessup or protecting and supporting the activities of Raymond. Moonrise Over New Jessup is a novel written by Jamila Minnicks during the time of the Civil Rights Movement — a period of intense social change and the national theme of desegregation. The story touches on topics of social integration and finding balance between personal relationships and the broader community.

On Friday, March 15, Minnicks presented as part of a panel at the New Orleans Book Festival. Specifically, she was part of a 45-minute seminar and discussion regarding the connection between fiction storytelling and setting called “Home and Away: The Concepts of Place and Belonging in Fiction.” The event was moderated by Tulane School of Liberal Arts Director of Creative Writing and Associate Professor of English Thomas Beller and included two other panelists — author Fatima Shaik and School of Liberal Arts English Professor Zachary Lazar.

During the discussion, Beller asked the panel of authors about the involvement of family in their fictional narratives, and to what extent personal relationships and perspectives of family are connected to their writing. Further, Beller asked about whether the closeness of familial source material affects the story being told or influences the effectiveness of the narrative, and whether asking for information from family introduced certain tensions or rather a sense of comfortability.

In response to these questions, Minnicks discussed how closely involved her family was to her novel, and the accuracy of information within it. In terms of the background and historical nature of the story, Minnicks included information and based the storyline on discussions with family, given their similarities to the characters and connection to the setting. Minnick shared that the story’s main character, Alice, is a “composite of all adults in [her] family,” and for that reason, it was incredibly important that the story and information were accurate.

“My family would give me all the business if I got it wrong and I would’ve deserved it,” Minnicks said during the presentation.

For Minnicks, it was incredibly important that the stories and background of her ancestors were acknowledged. Further, the novel was written for family and community, rather than personal purposes or aims to succeed in the book industry.

“It is, for me, a calling, because ultimately I wanted my family’s stories to be remembered in a way that gives them honor.”

Alya Satchu is a member of Tulane University’s Class of 2027. Originally from Chicago, she has a strong passion for journalism and writing and is currently pursuing a major in English with a minor in Sociology.

Banned Books and AI

By Sophie Colalillo

In spite of the wonderful celebration that is the New Orleans Book Fest, the dark cloud of our current struggle for free and open knowledge hung heavy through the weekend. Jesmyn Ward, a National Book Award winner, Tulane School of Liberal Arts Professor of English, and the Andrew W. Mellon Professor in the Humanities, expanded upon these ideas in her panel, “Open Minds: Protecting the Freedom to Write and Learn.”

As an English student, there is something very disturbing that not even four states away the dictionary is being banned from schools. There is a comfort in knowing that, especially here at Tulane, individuals with passion and love for reading, like Ward, will always fight for books.

Because books do not just contain knowledge; but, as Ward said, “through reading [kids] feel empathy and take that empathy out into the world.” Reflecting on my own life, I know that stories have provided me with not just a higher level of empathy but a sense of community as well.

I felt it when Ward read an excerpt from her novel, Salvage the Bones. Though I never lived through Katrina, I felt the warm water slowly seeping up, I saw the ghost of a blue ship in the distance; a powerful book like Professor Ward’s can allow us to step into the experience of someone else and begin to understand. So of course, as soon as I left the talk I bought a copy of the book — which has already been banned in some schools.

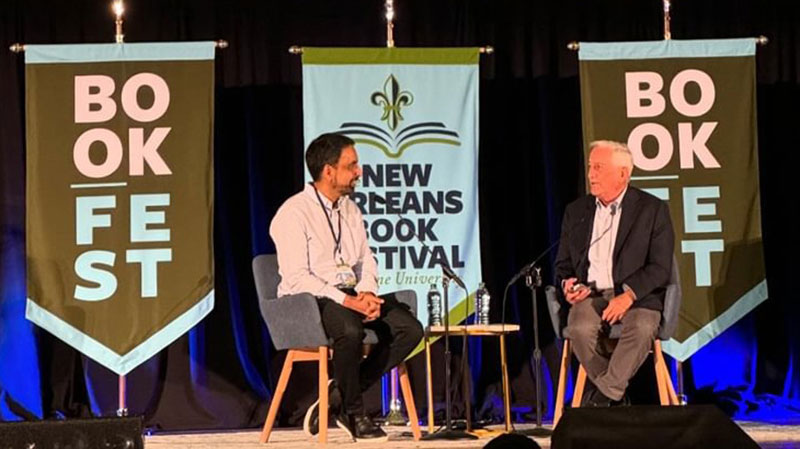

Later during the Book Fest weekend, I attended “The Future of Online Education in the Age of AI” with Sal Khan, moderated by Book Fest Co-Chair and School of Liberal Arts History Professor Walter Isaacson.

Like many other students, I’m unsure what to think of AI. Especially as someone looking to go into education, the prospect of a digital deus ex machina available instantaneously is kind of…unfathomable.

Which is what I thought before Khan’s talk.

Like many other students, Khan is…well, I would not have passed any high school math class without him. Seeing him was slightly spiritual. He created Khan Academy, an online learning platform offering access to hundreds of free videos, exercises, and any other study tool you could possibly need in any subject you desire.

What makes Khan Academy particularly helpful is, as Khan put it, “[the] on the fly aspect of it is important…[being] willing to think out loud…take a few zigs and zags.” The personalized aspect of the lessons allows not just a more engaging video, but also a sense of connection to form with the tutor (Khan, in most cases) and the material. I’m sure most high schoolers will recognize the black screen and tap of his digital pen from his videos; this level of transparency and casualness, combined with the re-playable nature of videos, allowed me to understand concepts I never thought I’d get.

Despite how we currently view AI, Khan made it evident that AI can be extremely beneficial to education. One of his students, he said, used AI as a kind of roleplaying chatbot, assuming the character of Jay Gatsby, so she could further understand the character. This kind of blew my mind. First, it was an immensely creative idea — an ability that Khan Academy’s own AI, Khanmigo, has as well — and second, that AI truly can be a beneficial tool in schools.

Another feature he mentioned was how Khanmigo specifically is trained to “push the student on [their] thinking,” rather than presenting the student with the answer; allowing a student to freely debate and explore their opinions without criticism. With technology like this, and people with the right intentions (Khan), AI will be an incredible tool for good.

Sophie Colalillo is currently a senior in Tulane’s 4+1 English master’s program, studying English and Italian. She transferred to Tulane in her junior year and will be graduating with a bachelor’s degree in May 2024.

Transcending Time, Place, and Reality with Yuri Herrera

By Alexandra Gassel

Against the brilliant background of a blossoming New Orleans spring, the third annual New Orleans Book Fest returned to Tulane's campus to a marvelous reception of literary lovers. Once again, asserting itself as a budding capital of literature, New Orleans welcomed many esteemed authors, poets, journalists, and industry experts to celebrate the role of creativity, veracity, and innovation in the literary world. More than simply a gathering of intellectuals, the New Orleans Book Fest is revered as a beautiful ode to the enduring power of storytelling. Here, in the embrace of Louisiana's deep cultural history, narratives transcend mere words and become part of our collective imagination, sparking conversations that surpass the boundaries of time and space.

For a book lover, there is no greater joy than the opportunity to hear an author speak on a book that has touched you deeply. I am lucky to say that this is precisely the joy I felt upon first seeing Tulane School of Liberal Arts Associate Professor of Spanish and Portuguese Yuri Herrera's name on the event list. Author of books such as (but not limited to) The Transmigration of Bodies, Kingdom Cons, and, my personal favorite, Signs Preceding the End of the World, Herrera has emerged as a prominent figure in contemporary Mexican literature. Sitting in on a conversation with Herrera feels akin to embarking on a literary journey transcending the boundaries of time, place, and even reality.

Beginning with a reading of his short story entitled Living Muscles, Herrera quickly leaves behind the constraints of the natural world and encourages the audience to "be free to be amazed" by the strange and unexpected. As the moderated discussion unfolded, Herrera embraced a level of authenticity and directness that contrasted with the mesmerizing blend of lyricism and wit that I have come to associate with his writing. With a wave of quiet laughter washing over the audience, he explained his profound dislike of the magical realism genre, pointing his audience to think of his work through a lens of science fiction instead. Though he rejects the notion that books must have a genre label, he carefully emphasizes the opportunity that sci-fi offers to construct a reality of one's choosing. Unlike genres grounded in realism, sci-fi does not pretend to mirror reality but instead envisions its own reality constructed from real-world observation. Having read several of Hererra's novels, I am no stranger to the mind-bending worlds he creates. Understanding the deep intentionality behind his frequent choice to disregard traditional reality induces a new understanding of his modest yet provocative prose. Hererra's work truly defies all labels, masterfully teetering on the edge of many genres without ever falling too deeply into a singular one.

Bringing us back into the real world, Hererra ended his discussion by giving the audience a glimpse into his upcoming book, Season of the Swamp, which is set in New Orleans. Hererra believes that in New Orleans, there is a version of the world that moves with fluidity and ease through time — one that laughs at the stagnation and passivity of other cities. Through this constant evolution, New Orleans can exhibit what Hererra calls an "excess of life" where energy, vibrancy, danger, and destruction dance together through the city streets. Never before have I held such an immense appreciation for New Orleans.

At the heart of Herrera's writing lies a deep reverence for the power of storytelling to illuminate the complexities of the human condition. Through his novels, he invites readers into richly imagined worlds that pulse with life and vitality, offering glimpses into the hearts and minds of his characters as they navigate the tumultuous landscapes of love, loss, and redemption. From the border towns of Mexico to the bustling streets of urban metropolises, Herrera's narratives transcend geographical boundaries, weaving together universal themes of identity, belonging, and the search for meaning.

As the curtains close on another unforgettable year of the New Orleans Book Festival, we find ourselves immersed in a symphony of words and ideas that linger long after the final word is spoken, the final page is turned. From the captivating discussions with esteemed authors to the vibrant exchange of literary passions among attendees, the festival has once again proven to be a testament to the enduring power of storytelling. Until we reunite once more beneath the canopy of live oaks and the enchanting melodies of jazz, let us continue to celebrate the transformative power of literature and the enduring bonds that unite us as lovers of the written word.

Alexandra Gassel is a member of Tulane University’s Class of 2025 majoring in English. Energized by deep analysis and nuanced interpretation, she finds joy in unraveling the complexities of texts — from modern novels to timeless classics — and plans to pursue a master's in English after graduating. With a passion for storytelling and a commitment to lifelong learning, she aspires to make her mark on the literary world as a thoughtful writer and discerning critic.