Sculptures Get a Home Makeover

Innovation and creativity abound in professor Gene Koss' Foundations of Glass and Intermediate Glass classes. With stay at home orders forcing his students out of the casting and glass blowing studio in the Newcomb Art Department, these liberal arts students put their ingenuity to work by using materials from home to create sculptures for their final projects. The results were inventive, resourceful, and thought provoking. We hope you enjoy these student samples illustrating their dedication and imagination.

Coleman Bishop (SE '22)

My name is Coleman Bishop and I’m from Great Falls, Virginia. I’m a rising junior majoring in psychology with minors in studio art and architecture design. In addition, I play club lacrosse here at Tulane. With limited access to materials for a sculpture, I decided to use the leftover paper plates I had and joined them together with clear tape, creating “The Plate of Life.” The design itself is a variation of the Flower of Life design of repeated circles. The process was like putting together a puzzle of paper plates and became very methodical after my second and final edition.

Sophie Fuselier (SLA '23)

I am a freshman from New Orleans, and I'm majoring in Classics. The title of the piece is "Stuck in Flight." I was inspired by the shape of the wooden board, which I thought could be well used to simulate motion. The effect I ended up with was birds clearly going somewhere, but then being frozen and idling in a single instant. With life being put on hold due to the pandemic, this piece is closely related to the way I view my current place in the world.

Cole Harmon (SLA '21)

Cole Harmon was born and raised in Saint Louis, Missouri. He is a member of Tulane’s Class of 2021, majoring in Philosophy with a focus on language, mind, knowledge. In addition to his sculptural and academic pursuits, Cole is also passionate about music and politics. “Being away from the studio, I knew I would have to get creative with the sourcing of my materials; and, while digging through piles of recycling and like junk, realized that I would not be satisfied with a simple shoebox-scale model. So, I decided to use the bulkiest and most plentiful material on hand: firewood. The design itself is largely inspired by the works of Andy Goldsworthy — works with which I became acquainted while watching ‘Rivers and Tides,’ a documentary of his assigned for the online portion of our Intermediate Glass course.”

Claire "Happy" Herold (PA '23)

My name is Happy Herold and I am from Decatur, GA. I am a rising sophomore. I enjoy fiber arts. My mom took glass from Professor Koss in the 80's. The inspiration for these sculptures was a Thai bamboo rice basket. I tried to emulate the basket in these three sculptures. My sculptures are made of plastic tubing traditionally used for plumbing and wire. I found these materials at my local hardware store. I experiment with many different materials, but found the most inspiration in the tubing.

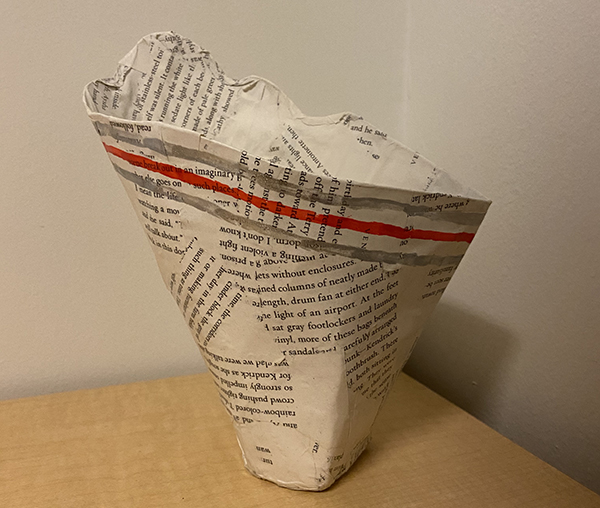

Anna Maija Li (SLA '23)

Anna Maija Li is a freshman Political Science and Studio Art: Printmaking Major from Palo Alto, California.

For this final project, I was inspired by food vessels. Things like cups and bowls are everyday objects and I wanted to take an artistic and functional approach to create the sculptures. I was inspired by fast-food french fry containers. I find something really nice about the curvature of them, even though they are made for fast food they seem to have a simple sort of elegance. I put my spin on it by creating a larger scale form out of paper mache. I wanted to play with the curves, and how it could comfortably sit in your hand. I added some details with paint to give it the graphic and color-blocked look that is pretty universal amongst fast food packaging. I like the juxtaposition of creating something artistic that would normally just end up as junk after a single-use.

Sofia Vila (SLA '23)

Sofia Vila is a rising sophomore from Miami, FL studying public health on Tulane's pre-medical track. She is also working towards a minor in studio art with a focus in glass. As an aspiring Obstetrician-Gynecologist, Sofia finds that the skills required to work successfully in an operation room and a glass studio are unexpectedly similar; both entail the comprehensive understanding and employment of fine motor skills while using tools, teamwork and clear communication with peers, as well as the ability to work smoothly under pressure. When her Intermediate Glass class was instructed to create a model for a blown glass sculpture, Sofia - as a fan of competitive cooking shows - was inspired to mimic glass with isomalt, a sugar alcohol often used to create stunning sugar art for stylish desserts. She achieved each bubble-like shape by pre-inflating a balloon to stretch the plastic into a rounder shape, refilling it with water, and then pouring hot melted isomalt over the top of the balloon, supported by a ceramic ramekin on a silpat mat. Combining these translucent structures with rusted steel, "SugarWheels" unites the fragility of glass and robust nature of metal alongside the repetition of a circular shape to create a paradoxical image of balance.