When we discuss the history of New Orleans, we often touch upon the common thread of human geography: where and how we have occupied this deltaic metropolis, and what those historical settlement patterns imply for future prosperity and sustainability—or alternately, hardship and risk.

Key to understanding New Orleans’ human geography is that adjective, “deltaic.” This region is a prime example of a river-dominated (fluvial) delta, in which the Mississippi’s enormous deposition of sediment overwhelmed the ability of Gulf currents to sweep it away. This explains why lower Louisiana, unlike adjacent coasts, protrudes into the Gulf of Mexico, and why the landscape rose only a dozen or so feet above the sea, with the highest areas (natural levees) occurring exclusively along current or former river banks. Smaller amounts of finer alluvium, meanwhile, settled farther back, becoming swamplands, while the thinnest deposits formed a marshy coastal fringe.

Being a fluvial delta means that freshwater is an intrinsic part of the soil body, and that renewed inputs of freshwater and sediment are needed to prevent this river-dominated delta from becoming sea-dominated, and subsiding into the Gulf of Mexico.

Enter humans into this equation, and the only long-term agricultural settlement opportunities for indigenous populations were on the higher natural levees. Coastal environs, rich in estuarine resources, were used only conditionally; when high water came, Natives relocated accordingly.

French, Spanish, and American engineers, on the other hand, set out to subdue the delta unconditionally—by building engineered structures such as levees and drainage canals to control water and make the land permanently habitable. But because that task was enormous and the technology rudimentary, early New Orleanians had little choice but to build New Orleans exclusively on the natural levees. How they sorted themselves thereupon brings us to the topic of human geography—specifically, residential settlement patterns by class, ethnicity, and race.

In terms of class, empowered families in early-1800s New Orleans tended to occupy the urban core, namely the upper French Quarter and the Faubourg St. Mary (today’s CBD). Why? Lack of mechanized transportation made inner-city living convenient, prestigious, and expensive, whereas life in the banlieues (outskirts) was quite the opposite. The pattern is an old one— “[European] city centres were inhabited by the well-to-do, while the outer districts were the areas for the poorer segments of the population”—and it carried over to New World cities. Encircling this empowered nucleus were middle- and working-class faubourgs, while farther out in the upper and lower banlieues and along wharves, canals, and the backswamp, were muddy, village-like developments of humble abodes to which gravitated lower-class and indigent families.

Overlaying these class patterns in antebellum (1803–1861) New Orleans was a broader ethnic geography. On the downtown side lived a predominantly French-speaking and Catholic demographic known as “the Creoles,” a pan-racial ethnicity unified by local nativity (having been born here), despite a three-tier division of castes, comprising free white, gens de couleur libre (free people of color), and enslaved black.

On the upper side of the city were found mostly English-speaking people of Anglo-American ethnicity, generally Protestant in faith and recently arrived from points north. They were known as “the Americans,” and while their uptown neighborhoods had fewer numbers of people of African ancestry, a higher percentage of them were enslaved compared to downtown.

Creoles and Americans competed economically and politically, and struggled to assimilate culturally. Immigrants to this complex multilingual society were caught amidst this rivalry, and formed uneasy alliances with either side depending on where they settled. During the 1820s to 1850s, laborer families mostly from Ireland and Germany arrived by the thousands and settled throughout the upper banlieue along the river (today’s Irish Channel), around the turning basins of the New Basin and Old Basin canals, and in the lower faubourgs of the Third District (“Little Saxony”). At the same time, immigrants from the Mediterranean, Caribbean, and South Atlantic realms (including French, Spanish, Italians, Haitians, Cubans, Mexicans, and Brazilians) usually settled among the Creoles, finding commonalities in their faith and generally Latin culture.

Those in bondage mostly worked as domestics or clerks, else were “leased out” on urban projects. At night they dwelled in proximity to their masters, in attached quarters or adjacent lodges. Ironically, this so-called “back-alley pattern” created a more heterogeneous racial geography in New Orleans than we see today.

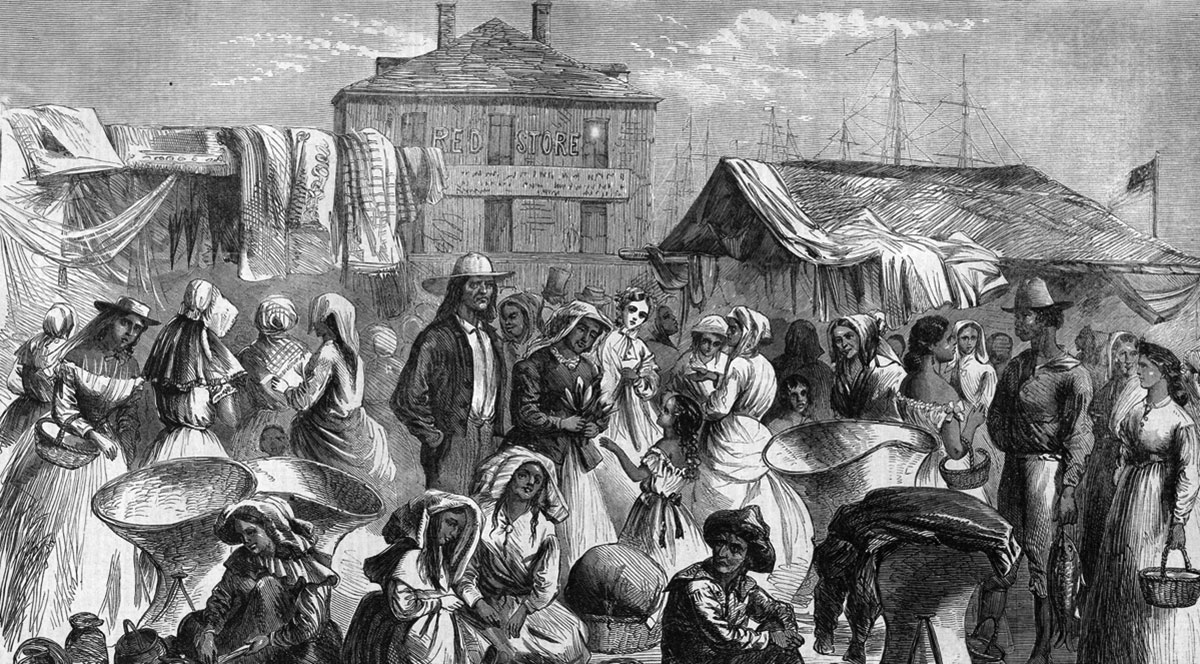

A particularly brutal aspect of life in the antebellum city entailed the temporary yet constant flow of victims of the domestic slave trade, which from 1808 to 1861 sent hundreds of thousands of African Americans out of the upper South and onto lower-South cotton and sugar cane plantations. Archival sources show that over a thousand people on average were sold annually in New Orleans in this era, with 4,435 purchases in 1830 alone (both figures are likely undercounts). Here too there was legislated geography: the City Council in 1829 passed an ordinance prohibiting the exposition and lodging of to-be-sold slaves in the urban core, while permitting it in adjacent faubourgs, for reasons of public image and health. By the late 1850s, over 35 slave depots, yards, pens, booths, or auction sites operated in New Orleans, which many historians readily identify as the nation’s premier slave marketplace.

Those people of color who were free, meanwhile, tended to settle in the lower Creole neighborhoods, particularly in rear precincts alongside working-class whites and immigrants. Here, elevation was lower, land cheaper, amenities fewer, nuisances more common, and environmental risks greater. This would become a recurring theme in New Orleans geography: whereas empowered families predominated the higher, opportunity-rich “front” of town, others were often literally marginalized to the “back” of town, near the swamp. Yet it is important to point out these spatial generalities abounded in exceptions, and it was not uncommon to find working-class families, white or of color, living adjacently to prosperous families, or for commerce and light industry to occur within steps of gardened mansions.

Four historical moments would radically transform settlement geographies in subsequent generations. One was mechanized transportation, starting with urban railways in the 1830s, which by the 1890s had grown into an expansive electrified streetcar system. These new methods of transport enabled wealthier people to move outwardly into the former banlieues, starting with the Garden District in the mid-1800s and continuing farther Uptown and along Esplanade Avenue to Bayou St. John by century’s end.

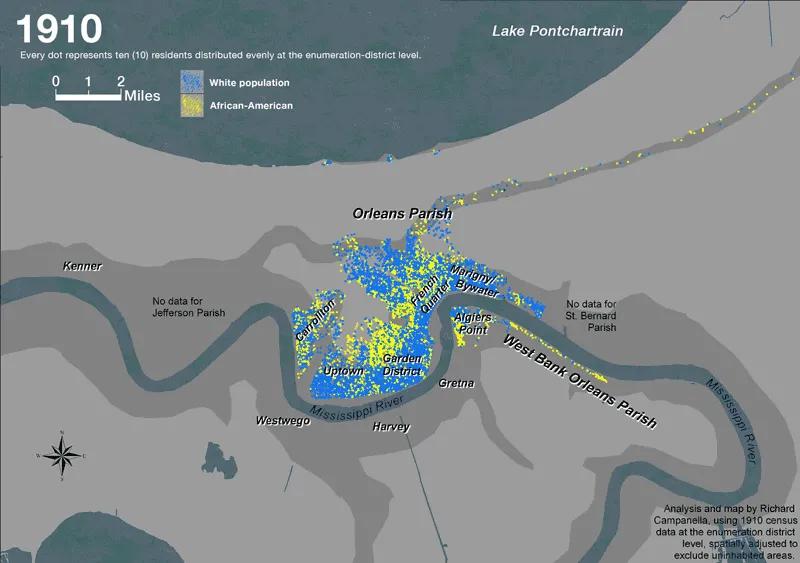

Concurrently, after the Civil War, emancipated African Americans emigrated to the city by the thousands, only to find mounting segregationist fervor and de-facto relegation to back-of-town spaces like today’s Central City. For decades to come, white-supremacist forces would exert ever-greater pressure on African American populations to live in certain areas and not in others. Rarely were the resulting black settlements without urban nuisances or environment risks.

Thirdly, the post-war and turn-of-the-century era witnessed changes in the geography of immigration. Irish and German arrivals declined, while those from Southern and Eastern Europe increased, including Sicilians, Croatians, Greeks, and Orthodox Jewish Poles and Russians. Small numbers of people of Asian and other origins also arrived, and as a whole, these cohorts would settle in a more clustered belt immediately surrounding the now-gritty urban core. This was the era, well into the 1900s, when New Orleans developed discernable ethnic enclaves with nicknames like “Little Palermo” (lower French Quarter), “Chinatown” (1100 Tulane Avenue), “the Jewish neighborhood” on Dryades Street (now Oretha Castle Haley), and “the Greek neighborhood” on North Dorgenois, not to mention the older “Irish Channel,” “Little Saxony,” the “Creole Seventh Ward,” and of course, “the French quarters.”

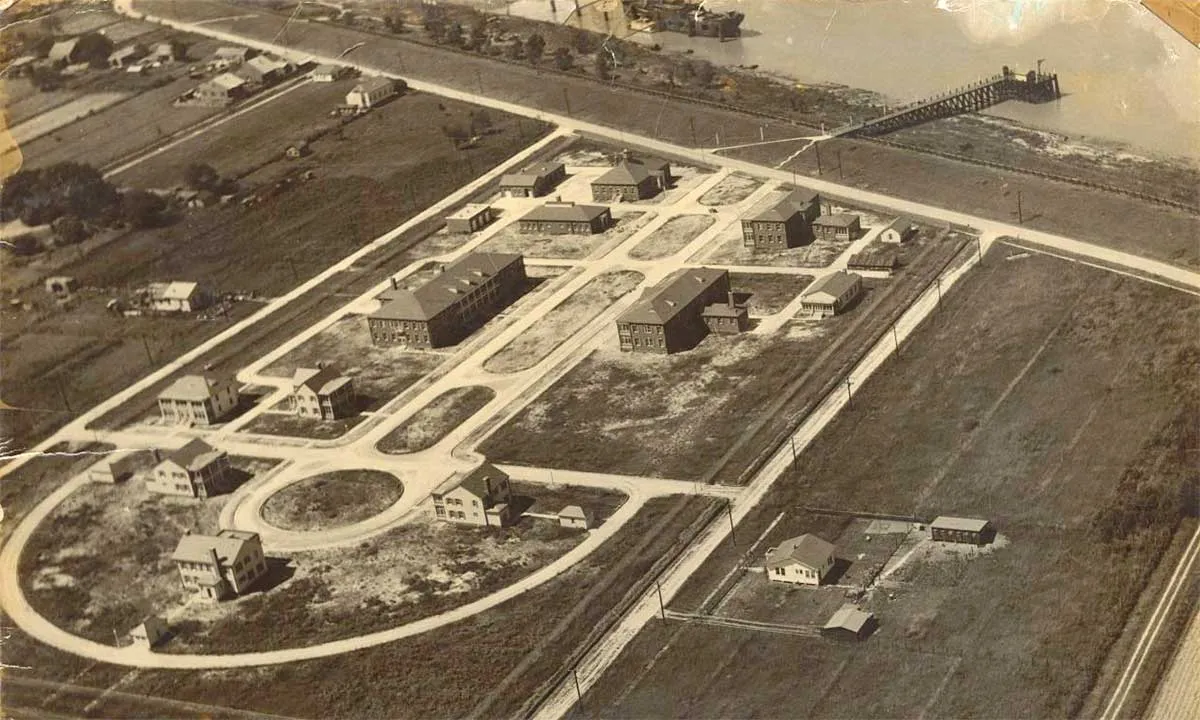

Finally, it was in this same turn-of-the-century era that the technology became available to drain the backswamp. Designed in the 1890s and fully functioning by the 1910s, the municipal drainage system lowered the water table, dried out lakeside lands, and enabled urbanization in Gentilly and Lakeview. White middle-class populations eagerly moved into these new auto-friendly subdivisions, as authorities sidestepped judicial rulings against explicitly discriminatory zoning ordinances by allowing the private real estate sector to create segregated neighborhoods through tactics such as racist deed covenants and redlining. The late 1930s also saw the first federal housing programs, which reduced the formerly heterogeneous racial geography of the city by segregating working-class occupants into white-only and black-only super-block “projects.”

White-only subdivisions in Lakeview and Gentilly imparted a twist to the old front-of-town/back-of-town pattern, which tended to position poorer black populations on lower ground. Now, white populations increasingly occupied the lowest and fastest-sinking soils, having been drained of their ground water. But confidence in levees and drainage technology seemingly neutralized these topographic concerns in the minds of most people, even as flood risk mounted—on account of urban sprawl, sinking soils, canal excavation in the east and West Bank, oil and gas extraction region-wide, and the deprivation of freshwater and new sediment by the levees along the Mississippi. Lower Louisiana starting in the 1930s would begin to lose upwards of 2,000 square miles of coastal wetlands, putting New Orleans at ever-greater geophysical risk.

The decline of de jure segregation during the 1950s–1960s may have brought the races closer together in the workplace and public facilities, but it occasioned the opposite in residential settlement patterns. White flight, followed by a broader middle-class exodus, made formerly diverse working-class neighborhoods mostly poor and black by the late 1900s. Fleeing families resettled westward and across the river in Jefferson Parish, eastward to St. Bernard Parish, and, after the construction of hurricane-protection levees, to the “suburb within the city” known today as New Orleans East. That area underwent a dramatic racial changeover during the 1980s, such that by the 2000s, the New Orleans metropolis comprised a predominately African American eastern half; a more white western half; a previously divested but now gentrifying urban core; and an increasing suburbanization of working-class and impoverished households (along with what were once euphemistically described as “inner-city problems”). It was in this era that greater New Orleans began spawning exurbs in places like Mandeville, Covington, and Slidell, complete with their own office parks and white-collar economic sectors.

The Hurricane Katrina deluge of 2005 and subsequent recovery efforts jostled and shifted regional human geographies, but did not fundamentally change them. Most socio-spatial patterns and controversies today, on the occasion of New Orleans’ 300th anniversary, derive from decisions, opportunities, relegations, and exclusions that were centuries in the making.