Opening Doors: Tulane Alumni Share Career Insights with Liberal Arts Students

Last week, a group of young alumni were invited back to campus to speak on a professional panel for current Tulane liberal arts majors, co-hosted by the School of Liberal Arts and NTC Career Services. The five panelists all graduated within the last five years and now work in a range of industries and professions, including publishing, consulting, solar energy, marketing, and operations.

The panel highlighted its breadth of represented majors and minors at Tulane — Environmental Studies, Classical Studies, English, Communication, Economics, Philosophy, Spanish, and the Strategy, Leadership & Analytics Minor (SLAM), and Political Science — and how studying these disciplines had informed their individual career pathways thus far. The discussion provided students with advice on leveraging soft and hard skills alike to navigate their early postgrad years, and stressed the importance of strategic networking and seeking out internships.

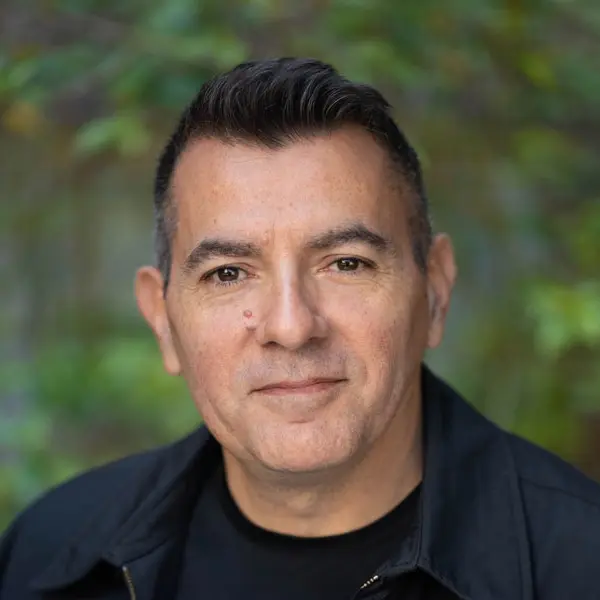

Conceived as an opportunity for School of Liberal Arts students to gain career insights, the event was moderated by H. Andrew Schwartz (A&S ’90), who graduated from Tulane's School of Arts & Sciences with a Political Science degree, and is now leading a think tank as the Chief Communications Officer at the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington, D.C.

Schwartz asked each panelist about their own trajectories, highlights and challenges, and addressed his executive words of wisdom to current students. “The difference between those of us who are working and those of us who are not working is literally night and day. So what can you do outside of that job to also be strategically thinking about the next thing?"

Enthusiasm and stepping up when given the opportunity to learn more were both also emphasized by the speakers. "Employers love young people who are happy to be there, who put their nose to the grindstone and try to master whatever it is they are doing," noted Schwartz. This willingness to adapt and explore added responsibilities was underscored by Ishanya Narang (SLA '20) who started at the ground level at GRUBBR and held roles in marketing and PR before being offered her current job of Director of Communications & Implementation at the start up

Following the discussion, some audience questions allowed for group feedback and closing thoughts from each of the panelists, before an informal networking session where students spoke with panelists one-on-one, putting the evening’s advice into practice.

Highlighting Young Alumni’s Journeys

The panel showcased the varied trajectories, demonstrating how a liberal arts degree often opens unexpected doors across industries.

- Sophia Gutierrez (SLA ’22): With a Classical Studies degree and a Master’s in English, Gutierrez credited a summer publishing course and making connections while interviewing for helping her land her sales associate role at Simon & Schuster. “Make sure you're being kind to people along the way," she reminded students, as she described having been referred to her current supervisor by a previous interviewer upon whom she had made a strong impression, despite not being selected for that role.

- Sahil Inaganti (SLA ’23): Now working in mergers and acquisitions at Nexamp, a solar energy company, Inaganti emphasized how his multiple majors — Environmental Studies, Political Economy, and Public Health — shaped his flexibility and approach to working. “I benefited from taking a variety of classes,” he explained, noting the importance of a broad perspective and maintaining hobbies to keep oneself actively engaged and interesting. He also shared that his strategy at any new job was to leverage his own inexperience, making a point of asking questions and learning as much as he could from the start.

- Charles Lieberman (SLA ’22): As a consultant at Deloitte, Lieberman’s background in Economics and Philosophy have been invaluable. He shared how interpreting Socrates’ texts sharpened his critical thinking skills, now making complex business documents seem straightforward. “The nature of a liberal arts education is fluid and exploratory,” he said. “Curiosity has been my biggest strength in my current job.”

- Stashia Thomson (SLA ’23): Now in a dual role across sales and marketing at Atomic Black Spirits and The Drinkable Company, Thomson emphasized how her Spanish minor augmented her social skills, giving her a “touchpoint to connect with people.” She encouraged students to start networking early, sharing her belief in building connections to achieve career success, and learning about her audience both before and during sales meetings.

- Ishanya Narang (SLA ’20): Working as Director of Communications & Implementation at GRUBBRR, Narang discussed the importance of pursuing independent ventures. “One thing liberal arts students shouldn’t shy away from is entrepreneurship,” she asserted. “There’s no better way to control what you want to do than doing your own thing. We have good cultural and social understanding of problems — in a way that sometimes other degrees may lack — so having that cohesive education gives you a very good perspective on what really matters.”

Liberal Arts as the Foundation of Success

Each panelist underscored how their humanities and social sciences studies have been integral to their early career outcomes. From critical thinking to creativity, debate, adaptability, and constant curiosity, they proudly identified themselves as chameleons and high-achievers whose potential was only starting to really show.

Gutierrez humorously, yet profoundly, summed up a common misconception about college majors: “Oh, what are you going to do with an English degree, read a book? But that’s exactly what I do for my job every day — that is a profession, in fact.” Lieberman added, “I think the nature of a liberal arts education instills a very deep sense of curiosity. And when I apply that to my actual job, I would argue that curiosity has been my biggest strength.”

Tactics for Students

The importance of internships and networking in opening doors to career opportunities was persistent throughout the evening. Schwartz, drawing from his own experiences, emphasized that internships help position students to be “in the right place at the right time.” Narang added, “Once your foot is in that door, how do you make the most out of that opportunity?”

Thomson encouraged students to start building connections early, while Lieberman and Inaganti highlighted cross-industry communication as tools for growth. The panel’s practical focus resonated with students in attendance, who lingered to connect with the alumni during the post-panel networking session. This format for asking questions, exchanging ideas, and building relationships helped bridge the gap between education and career success.

Reflecting on the event, Lieberman offered an apt summary: “With the School of Liberal Arts, your options are unlimited. Maybe there’s less structure — but there’s more opportunity.”

Panelists answer questions from the audience during the Young Alumni Perspectives discussion.

Sophia Gutierrez (SLA ’22) shares her insights during the Young Alumni Perspectives Panel.