Student Summer Spotlight

Summer in Ireland

Tulane's Summer in Dublin study abroad program offers students an immersive cultural experience while exploring the rich history and vibrant contemporary life of the Emerald Isle.

Cleo Doran (SLA ‘25)

As someone with Irish heritage and citizenship who had not previously visited the country, my hope was that this program would offer a comprehensive introduction to the island and its culture. I can confidently say that this program succeeded in offering that type of immersive education. I feel most thankful that I was able to participate in a program that offered intellectual stimulation and meaningful instruction as well as genuine fun and independent exploration.

The Summer in Dublin program is truly a highlight of my Tulane experience so far and I would enthusiastically recommend it to anyone looking for a fun, immersive, and enriching summer study abroad experience.

Annabelle Jones (SPHM ‘26)

This summer I went to Dublin, Ireland to study anthropology. The highlight of the trip was getting to see a variety of different historical and archaeological sites. The country is small enough to make cross-country trips manageable, so we were able to visit multiple sites each day.

The experience was incredibly unique in that I was able to learn in a new and exciting way. From traditional storytellers to museum exhibits, there were many opportunities to learn and grow. It was amazing to see the things I studied in person, making the material much more tangible and relevant.

Students are given a plethora of information through all forms of media, books, videos, and lectures. This allows different types of learners equal opportunity to grasp the history. We were provided tickets for guided tours, museums, and field trips; all of which were a joy to be a part of.

Syd Stone (SSE ‘27)

This summer I had the privilege of joining Tulane’s study abroad program. During the trip, I attended all of the history classes offered in Dublin, Ireland. These classes, “Protest, Prohibition, and Prostitution” and “Irish Culture, History, and Society,” were so fun and enlightening. I do not exaggerate when I say these classes were the highlight of my summer.

I am also a history major who has always been fascinated by Irish history and culture. Because of this program, though I am only a sophomore, I am already halfway to my degree..

This program was incredible and I highly recommend everyone try it.

Leah Starr ( SLA ‘25)

I didn’t originally plan on choosing the Summer in Dublin program for my summer study abroad experience, however I am extremely glad I did.

Even though I am not a history major, I really enjoyed the two history classes I took on this trip. We had a field trip almost every day, usually multiple trips in a day. We also took a four-day fieldtrip around southern Ireland and a day trip to Belfast. All of these trips gave me the opportunity to experience more of Ireland than I could have on my own.

Mandel Palagye Program for Middle East Peace

The Stacy Mandel Palagye and Keith Palagye Program for Middle East Peace offers students an opportunity to learn about the complexities of the region’s long-standing conflict in association with non-governmental organizations, think tanks, and academic institutions.

Laura Brawley (SLA ‘26)

Learning about the conflict from these three different perspectives helped us to immerse ourselves not only in the historical facts and peace theories related to the conflict but in the lived experiences of Palestinians and Israelis through Arab and Israeli film and literature.

The intensive nature of the classes led to many late-night conversations with my classmates about the readings and homework, as well as our own changing perspectives related to the conflict. Being able to engage in these discussions with my classmates was one of the most beneficial parts of the program, as we were able to learn from each other.

We even got the chance to speak to Palestinian and Israeli politicians, as well as senior Huffington Post Correspondent Akbar Shahid Ahmed. Hearing from the experts during this period of violent conflict was as sobering as it was enlightening, and highlighted how brutal the reality is on the ground for long-suffering Gazans. Hearing from Amal-Tikvah, an Israeli/Palestinian grassroots peace organization, was particularly inspiring. The women who spoke to us had lost so many people and witnessed so much suffering but remained committed to the peace process through their work.

Adrian Serieyssol (SLA ’27)

This summer I had the pleasure of taking part in Tulane’s Mandel Palagye Program for Middle East Peace with 14 other Tulane students. Over the course of four weeks, we learned not only about the roles of modern-day actors in the conflict between Israel and Palestine but also about theories of conflict resolution and the history of the entire region, going back to the Philistines. At the start of the program, few of us knew one another, but after the first two weeks of the Tulane campus portion, we had grown to become friends.

After two weeks of classes in a familiar environment, we flew to Washington, D.C. If not for the October 7th attacks, the second half of the program would have been held in Israel. Instead, we spent our time in D.C. visiting think tanks and hearing brilliant people talk about how they see the conflict. My personal favorite was The International Crisis Group. It was great to explore our beautiful capital.

Environmental Studies in Ecuador

The Tulane Initiative for Education, Research, and Action (TIERA) is a unique program based in Ecuador designed to equip students with the knowledge and skills necessary to address complex social challenges.

Jude Hutkin (SLA ’26)

To learn from other individuals halfway across the world is a special thing. Not only was I able to learn in this respect but I was also able to teach. Fellow scholars and I performed a climate change workshop where we educated the local community about climate change’s causes, effects, ways of mitigation, and the role of carbon in it all. The presentation was quite fulfilling knowing we were giving back to the community in terms of education, and not only extracting information for our own projects.

You truly never know where you will end up with environmental studies. One summer I was studying plants and their uses for sustainable infrastructure and the next I was performing interviews with Ecuadorian landowners while measuring carbon storage on reforested plots of land!

School of Liberal Arts September 20 Newsletter

Dear School of Liberal Arts Community,

Our first communication of the academic year comes slightly delayed by emergency preparations for — and recovery from — Hurricane Francine. But as a welcome win, we’ve already made it through a major weather event! And from the other side of the storm, I am particularly excited about this coming year.

This is my seventh year as dean, and I greet every new fall semester with a combination of anticipation for all the activities of the coming months and joy over the return of faculty, staff, and students to our buzzing campus.

I'm exceptionally proud to introduce our newest members of tenure-line & professor of practice faculty, who bring not only expertise and experience to Tulane, but who emerged from national searches that engaged so many top colleagues from the humanities, social sciences, and arts. Meet them below.

In June we launched the much-anticipated first major renovation of Newcomb Hall since its completion in 1918. New event spaces, areas for interdisciplinary programs, enhanced classrooms and fresh collaboration zones will be the purview of the entire community.

Next month will see a new academic event, the Flowerree Symposium, born out of a cross-school partnership with experts in the environmental sciences. Additionally, our STEM2 Studies initiative is a sequence of team-taught courses pairing SLA faculty with several peers from SSE and SOM. Then, our second Mellon-funded Sawyer Seminar gets underway with a series of speaking events on the global and domestic contexts for understanding reproductive health. [...]

Welcoming New 2024-2025 Liberal Arts Faculty

Faculty in the Field: Summer Studies

Voice Professor Trains A-List in Local Dialects for the Big Screen

Amy Chaffee, Associate Professor of Theatre & Dance, spent her summer with a different set of students, providing linguistic coaching to actors Scarlett Johansson (Fly Me to the Moon) and Channing Tatum (Deadpool & Wolverine).

Fulbright Seminar Explores City History: Art, Academia & the French Quarter

English Professor T.R. Johnson led a Fulbright Program seminar on New Orleans’ rich cultural history, closing with a quarter walking tour — in which the group even had a chance run-in with famed local photographer Frank Relle (SLA '00).

Student Spotlights: Summer 2024

Our call for start of year stories found students exploring Irish castles, conducting ecological research in Ecuador, and finding new perspectives in D.C. Read about their summers abroad.

Upcoming Featured Events

Illustrious Alumni Concert Piano Series

A show to launch the season! Five alumni — former students of our own Faina Lushtak — who have gone on to pursue a Doctor of Music Arts will return to the Dixon Hall stage. This series seeks to present great music literature through performances by artists of the highest caliber.

Featuring Ben Batalla, Scott Cohen, Francesca Hurst, Anna Savelyeva, Michael Rigney, & Faina Lushtak.

Tuesday, October 8, 2024, 7:00-10:00 pm | Free and Open to the Public

Assistant Professor, Political Science & Environmental Studies

The Inaugural Flowerree Symposium at Tulane University

The inaugural Flowerree Symposium, to be held on October 8, 2024 on Tulane’s Uptown Campus, will feature a conversation with leading scientists and policy scholars, both from within our university community and beyond. Political Science Assistant Professor Joshua Basseches is a featured speaker, don't miss his talk: Political Economy of State-Level Renewable Energy Policy.

Tuesday, October 8, 2024, 7:30 AM-6:00 pm

*SLA Faculty Fellows are recruited shortly after completing their PhD studies and pursue a tenure-track professor path.

New Orleans Culture Through the Lens of Art and Academia

Last month, English Professor T.R. Johnson led a seminar for scholars from 20 different countries on the literary and cultural history of New Orleans and a walk / talk around the French Quarter and Congo Square. The opportunity was part of a Fulbright Program called Study of the U.S. Institutes for Scholars and Secondary Educators (SUSI Scholars).

Of the tour, Johnson shared “I really enjoyed hosting these international professors and having the opportunity to represent Tulane and New Orleans. Their disciplines, ranging from history, sociology, and law to media studies and linguistics, made for a lively discussion throughout the day.”

While on the walking tour, the group sought shade in a courtyard that happened to be behind the gallery of celebrated New Orleans photographer Frank Relle. Relle, an SLA alumni (’00), noticed the group and joined them for a few minutes. During that time, he took some photos of the scholars, giving them a unique New Orleans experience of life imitating art.

“Our interaction with Frank solidified for the group the connection between local artists and everyday life here in New Orleans,” Johnson continued. "These artists are engrained in the fabric of the city and the timing could not have been more perfect.”

English Professor T.R. Johnson, engages international scholars with New Orleans’ literary and cultural history, enhanced by an encounter with photographer Frank Relle.

Voice Professor Brings Louisiana Dialects to Big Screen

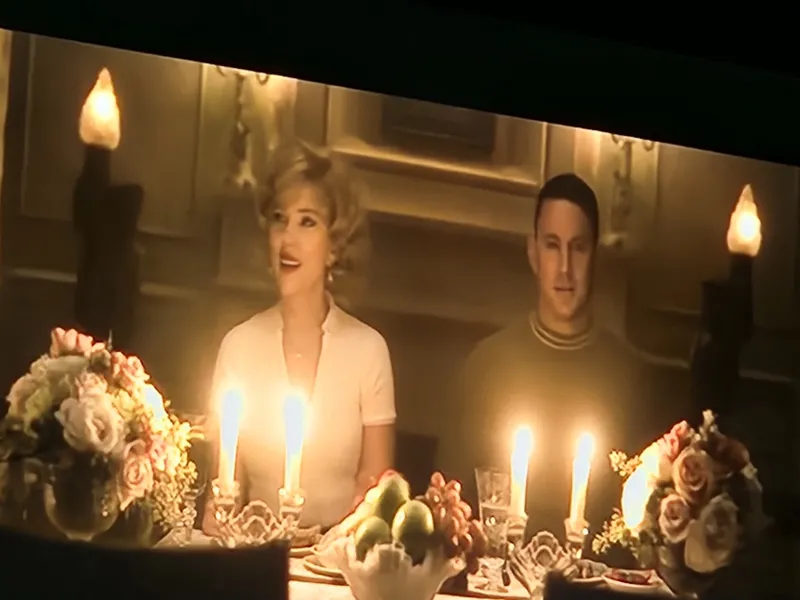

As a dialect designer and coach, School of Liberal Arts Theatre & Dance Associate Professor Amy Chaffee has honed her expertise in crafting authentic accents for film and television. In this article, Chaffee shares her experience working with actors Scarlett Johansson and Channing Tatum on major motion pictures, revealing the fascinating process of crafting believable accents for some of Hollywood's biggest stars.

My research as a dialect designer at Tulane and in greater southern Louisiana has led me to work on two major films over the past few years. I served as a coach to Scarlett Johansson in Fly Me to the Moon and Channing Tatum in Deadpool & Wolverine — researching, designing, and teaching Louisiana accents to both actors.

I have worked as a dialect designer and coach in film and television since 2007. Similarly to how a costume designer or production designer creates the “visual reality” of a film world, I help create the “auditory reality” of a film. I often say that if I did my job right, you would never know I was there.

In Fly Me to the Moon, Scarlett plays a con artist-turned-advertising executive who is recruited to promote the space exploration program for NASA. Her character slips easily in and out of accents to create affinity with her “mark.” Scarlett, in addition to starring, was also an executive producer on the film and had full reign to improvise her lines. This meant getting her sounds fit for anything she felt compelled to play. Her character is asked to sweet talk a Louisiana Senator, which required her to drop flawlessly into an accent somewhere on I-10 between New Orleans and Baton Rouge. Later, she tricks another Senator into believing she is an Atlanta native and graduate of Georgia Tech — requiring another sound palette to master. Reviews of her acting work do not mention the accents. But, again, in my line of work, if no one talks about the accents, it’s usually a good thing — the story held and the character was seamless.

Deadpool & Wolverine was more daunting. The co-writers, Deadpool star Ryan Reynolds and Director Shawn Levy were both totally down for Channing to ad-lib and improvise as “Da Gambit.” Again, the challenge of prepping him with more than just the written lines included the mastery of the sounds so he could feel as playful and easy as the tone of the movie. Channing wanted to work very faithfully to the Cajun sound, although his character was brought up in the streets of New Orleans. To find this unique blend, I sourced and recorded a few Cajun gentlemen in their 70s and 80s who had grown up in Mamou, Ville Platte, and Eunice but spent their adult lives in New Orleans. They told stories peppered with Cajun French sayings and good-hearted insults, code-switching easily and sliding in and out of French, as many Cajuns do. Channing loved the resources and asked for a list of (and translations for) all the insults they shared. He used at least three of these Cajun French phrases in the film. These lines are special easter eggs for Cajuns who see the film. The performance has been critically acclaimed for its humor and “insider baseball” appeal to the fan base.

Tulane’s multidisciplinary community has been invaluable for my work. From the published research of School of Liberal Arts Professors Thomas Klingler and Nathalie Dajko, who have written about the Creole and Cajun dialects, to the Hogan Archive of New Orleans Music and New Orleans Jazz housed within Tilton Memorial Library, I have an amazing base from which to draw. However, it is the living resources of the greater New Orleans and southern Louisiana communities that help me create my best designs.

Video Village View on Fly Me to the Moon