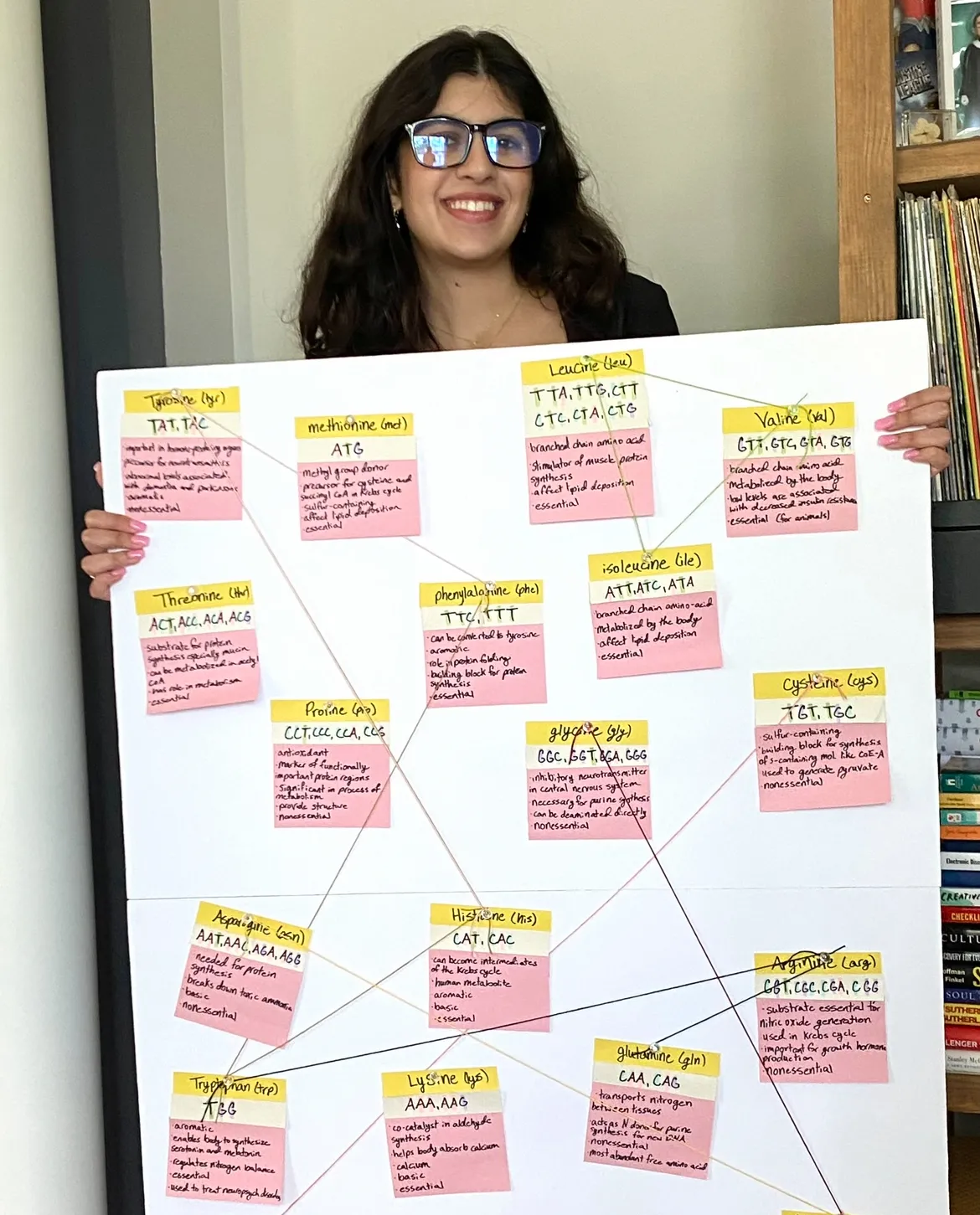

A Roadmap for Understanding

“We all have our own light, our own perspective, to shine,” explains Tulane School of Liberal Arts alum Mwende “FreeQuency” Katwiwa (SLA ‘14). A Kenyan, immigrant, queer storyteller, FreeQuency (they/their) is the 2018 Women of the World Poetry Slam Champion, was a 2017 TEDWomen speaker, and their writing has been featured in publications such as the New York Times, OkayAfrica, Teen Vogue, and Huffington Post.

FreeQuency’s creative practice centers on their everyday actions and interactions, addressing topics of activism, #BlackLivesMatter, reproductive justice, and LGBTQ advocacy. Like most individuals and creative practitioners, the Covid-19 pandemic has been especially challenging for their work. “To be an artist before Covid-19 was pretty precarious work, unless you were coming from a privileged position,” said FreeQuency, explaining that many artists work multiple jobs or travel extensively to support their livelihood. “Our moment has heightened economic and societal fractures and highlights what it means to really dedicate your life to being an artist.”

While a student at Tulane, FreeQuency studied political economy and African and African Diaspora Studies (now Africana Studies). They were engaged with student groups such as the Black Student Union, where they resurrected the Black Arts Festival in 2014, and campus offices such as the Office of Multicultural Affairs and the Center for Public Service, where they received the Carolyn Barber-Pierre Trailblazer Award and served as the inaugural Bruce J. Heim Foundation Fellow, respectively. However, much of their involvement and creative voice emerged by witnessing and experiencing injustices alongside other Black students. As writers and activists visited Tulane, FreeQuency began taking advantage of direct time with them, and often gave opening remarks or an opening performance for these visitors. Years later, FreeQuency now extends this opportunity to university students when invited to speak or lead a workshop at universities.

“So much of my writing is in response to what I’m doing—the context I find myself in, the community I find myself in, the personhood I find myself in,” said FreeQuency. “But Covid-19 has challenged all of this.” Not only are their methods for creating shifting during this time due to quarantining and social distancing, but the reciprocal relationship between performers and audience members that occurs in real time is also transforming with a move online. In response, FreeQuency is writing as a more personal practice of processing experiences, feelings, and thoughts that this year continues to bring to the cusp, from political tensions, to fighting systemic racism, and mental and spiritual health during a pandemic.

“A story is a roadmap for understanding,” explains FreeQuency. “Writing is a powerful art, personal tool, and bridge between the sciences and arts—stories help us understand every aspect of the world around us.” Today, FreeQuency urges audience members to listen to the stories being told around themselves, and encourages everyone to consider what they want to say with their voice and time, continuously and consciously returning to the question: what is the story for me to tell?

Alum Spotlight – Mwende “FreeQuency” Katwiwa

By Emily Wilkerson

Tulane School of Liberal Arts alum Mwende “FreeQuency” Katwiwa (SLA ‘14).

Becoming//Black, FreeQuency’s first collection of poetry and their newsletter, is available on Amazon. They continue to run a weekly poetry series at Paza Sauti (which means “raise your voice”), an artist and activist collective in Nairobi, and are currently working to raise $25,000 for the Trans & Queer Solidarity Fund Kenya.